Table of Contents

Where there’s steam, there’s shitamachi

Shitamachi (下町) is hard to define, but it doesn’t mean “downtown,” as it’s often translated. In her 1964 smash “Downtown,” Petula Clark sings of a place where “the lights are much brighter” and “when you’ve got worries, all the noise and the hurry seems to help…” Most Osakans would head to the Kita (Umeda) or Minami (Shinsaibashi / Namba) districts when they’re “alone and life is making [them] lonely” (Clark again). A more accurate translation of shitamachi would be “low town,” and to quote myself in the article on Chuo Ward, “the ambience of old-school working-class districts is a hard-to-describe mixture of gritty, picturesque, and nostalgia-inducing (even if you weren’t around during the era it makes people nostalgic for).” Signs that you’re in a shitamachi area include narrow streets and alleys, aging wood-frame buildings at times decrepit to the point of collapse, cheap eateries and tachinomiya standing-only bars, shotengai shopping arcades lined with mom-and-pop shops, small workshops and micro-scale factories, clusters of potted plants on the pavement in front of houses, laundry hanging in the street, and public baths (sento, local bathhouses, as opposed to larger, newer, more luxurious super sento).

The numbers of shopping arcades and public bathhouses are directly correlated with a neighborhood’s degree of shitamachi-ness, partly because these areas, being less desirable real estate, are less prone to the demolish-and-build-anew mentality that sadly dominates more upscale parts of the city. Also, shitamachi denizens are more likely to depend on these amenities, for shopping (due to a lack of large supermarkets or shopping centers), or for bathing, as older apartments often lack baths. According to the Osaka Prefecture public bathhouse trade organization website Osaka Sento Guide 268 (a dad joke – 268 can be read as furoya, another word for “bathhouse”), Ikuno has the most sento (24) of any of Osaka’s 24 wards.

Lost in the Labyrinth

The maze of endlessly branching shotengai to the southeast of Tsuruhashi Station is the most bustling and vital of such areas surviving in Osaka today. Nearest the station is a grid of narrow arcades, always thronged on weekends, full of eateries (I’ll skip the details since they merit an article of their own – check out this previous Osaka.com article for a start), shops selling all manner of Korean and Japanese ingredients, and clothing stores selling everything from traditional Korean formal wear to trashy youth fashions and classic Osaka obachan (older woman) finery. Osaka obachan, famed for their gaudy attire, penchant for animal patterns (sometimes multiple species at once), permed and dyed hair, and brash attitudes, once roamed the city in great numbers, but today they’re an endangered species, possibly because they became such a media-parodied trope that they grew self-conscious and toned down the rhinestone-studded leopard-patterned blouses and the rest. If you’re on the hunt, though, Ikuno Ward is a pretty good place to spot them.

Further to the east is a less orderly network of arcades, the main artery of which is the winding Tsuruhashi-hondori Shotengai. The district is bounded on the east by the north-south avenue between Tamatsukuri-suji and Imazato-suji known, though not marked on street signs as far as I can tell, as Sokai-doro (literally “Evacuation Road,” as it was designated during World War II), where the Tsuruhashi Fresh Fish Market was recently demolished for seismic and other code violations after a long legal battle. Just to the southeast of Tamatsu-3 where Sennichimae-dori and Sokai-doro intersect, find Nobeha no Yu, one of Osaka’s greatest super sento.

Many bathhouses are named “_____ Onsen” without actually drawing on natural hot springs (see photos near the top). Nobeha no Yu does, though, and it’s the best of its kind I’ve been to in Kansai, especially because of its huge ganban-yoku area where you lie and sweat it out on various kinds of hot rocks (or here, you can sprawl on a Korean-style mat floor where staff sometimes fan you with fragrant steam).

This commercial district has roots in black markets that thrived amid the rubble in postwar Osaka. Tsuruhashi was notorious as what the media termed a “dark zone,” home to the headquarters of over 20 street gangs and yakuza groups. There were black markets all over the city, most of which have left little trace, but this one had the clout to negotiate with the Osaka City authorities and receive official sanction in 1947, leaving it intact, legal, and thriving to this day.

The hanryu (“Korean wave”) has been sweeping Japan for so many years now that it seems less a craze and more the status quo, and it has propelled a surge of youthful visitors to the area, especially young women. The area around Tsuruhashi Station is thronged on weekends, and streets lined with boutiques and eateries are increasingly lit with colorful neon signs, inspired in part by the Korean TV drama Itaewon Class set in a glowing nightlife district of Seoul. Ikuno Ward’s great mecca for Koreaphile youth is Momodani Korea Town, discussed below.

The Name That Vanished from the Map

Osaka residents who’ve read Min Jin Lee’s acclaimed novel Pachinko, the multi-generational saga of a Korean family that emigrates to Japan, may have wondered about Ikaino, the ghetto where they settle on arrival in Osaka. There is no such place name today, but Ikaino (猪飼野, literally “boar keepers’ field”) was the name of the area for centuries before it was renamed Ikuno (生野, lit. “living field” or “fresh field”). Considering the unruliness of Japan’s wild boars, it’s likely that the animals kept were actually domesticated pigs brought over from the Asian continent. This would have been one of the specialized occupations of toraijin – immigrants from Eurasia with recorded presences dating back to the 5th century – along with taming birds of prey and building or decorating temples and shrines. The name Ikaino remained in common use well after Ikuno Ward was established in 1943, and it’s said that letters from Korea would arrive with only “Nihon, Ikaino, [name of household]”) written in katakana on the envelope.

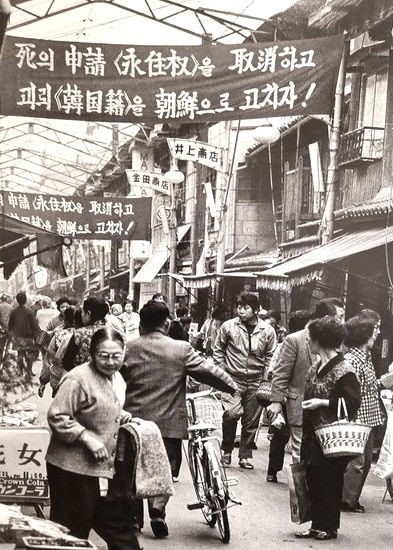

By the 1970s “Ikaino” had vanished from maps and addresses, evidently due to prejudice and concern over the name’s stigma causing a decline in property values. However, some locals continue to use the name, and the official Ikaino danjiri float, rumored to be dyed with baboon’s blood (?!), still appears in the Miyukimori Tenjingu summer festival the second weekend of July. Readers who attend the festival, please look for the Ikaino float, write in to Osaka.com and give us your opinion about the veracity of the baboon-blood thing.

After World War II, Ikaino continued to burgeon as an enclave with approximately 40,000 Korean nationals. Today, about 20% of Ikuno Ward’s population reportedly has Korean citizenship, but the number is likely underestimated, and many others with Japanese citizenship are wholly or partially ethnic Koreans. The area is recognized as the largest Korean community in Japan, extending into neighboring Higashinari Ward north of Sennichimae-dori. Many residents are descendants of Koreans who migrated to Japan during its annexation of Korea from 1910 until the end of World War II in 1945. They were often recruited for grueling, low-wage manual labor such as reconstructing the embankments of rivers, and one can see parallels to the Chinese immigrants who built railroads in the United States only to face discrimination and exclusion afterward.

Ikaino was dotted with small factories manufacturing goods such as cheap sandals. The Korean-Japanese YouTuber and Ikuno native who goes by Joe Vlog, from whose introduction to Ikaino I harvested crucial info for this article, recalls iron filings covering children who chronically skipped school to help with family businesses. As they reach adulthood, children born in Japan to Korean immigrants or second-generation parents, or of mixed Korean and Japanese ethnicity, face decisions about their nationalities and identities, often going by Japanese names while retaining their Korean names in official records.

From Ikaino to Ikuno

Originally part of Higashinari Ward, Ikuno became a separate entity in 1943. Many wards were subdivided in this way as Osaka’s population surged in the early 20th century. For a time during the industrial boom and population growth of the Dai-Osaka (大大阪, “Greater Osaka”) era, roughly the 1920s and 1930s, it was Japan’s largest metropolis. In an alternate history, who knows where this city might be today?

Prior to those years, Ikuno was countryside dotted with small villages and home to less than 5,000 households. By 1940 the population had increased nearly tenfold, and by the 1950s Ikuno was the most populous ward in Osaka, with almost 10% of the city’s people. Today, despite a relative lack of high-rises and a preponderance of old houses, low-rise wood-frame apaato, and nagaya one-story row houses, it remains one of the more densely populated wards in a city that’s pretty packed in general.

Japan’s Oldest Bridge?

Tsuruhashi derives its name from Tsuru-no-hashi (“Cranes’ Bridge”) over the Hirano River. The river still exists, though it’s some distance away from the site of the original bridge, now marked with a stone monument. The Hirano River was also known as the Kudara River, after the ancient Korean kingdom of Baekje (Kudara in Japanese), and Ikaino was also called Kudarano. Another nearby river, no longer flowing aboveground, was called Komagawa, “Koma” being a Japanese reading of another ancient Korean kingdom, Goryeo. Komagawa was corrupted to Nekomagawa (猫間川), neko meaning cat. This former river’s name is also attributed to the many feral cats living there, from which some people made a living by capturing them and selling their skins as coverings for musical instruments. As a cat person, this is one of those things that makes me glad I live in modern times. The former Nekomagawa River was replaced by the Osaka Loop Line along the east side of Osaka Castle Park, and survives today as the name of an avenue (Nekomagawa-suji) in Ikuno Ward, one of those meandering city streets that indicate the road was once a waterway.

Tsuru-no-hashi is mentioned in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, c. 720), the oldest instance of a bridge recorded in Japan. According to the chronicles, Emperor Nintoku ordered a small bridge to be built over the Hirano River, and the many cranes (tsuru) flocking the area inspired the name. The river was rerouted and its former course covered over in the 20th century, but at the former site of the bridge at 3-17-22 Momodani, about a 15-minute walk from the east exit of JR Momodani station, is a monument where some of its pillars still stand.

From Cranes’ Bridge to Peach Valley

Momodani (lit. “Peach Valley”) is known as the home of Osaka Korea Town, often called Ikuno Korea Town. It’s one stop clockwise from Tsuruhashi on the JR Loop Line, but a great way to experience the Ikuno vibe is to walk from Tsuruhashi down to Momodani along Tsuruhashi Hondori Shotengai or one of the other shopping arcades, or wander aimlessly through the narrower streets, making your way generally south. The west entrance to the main drag, Miyuki-dori, is about ten minutes’ walk east of JR Momodani station. The pedestrian-only (in the daytime) shopping street is instantly recognizable by the colorful Korean-style gates and hordes of people, especially on weekends. Amid the youngsters queuing up for cosmetics, K-pop idol merchandise, and the latest Korean junk food, there are eateries and shops such as Yamada Shoten where you can find varieties of kimchi you never thought possible (celery, yam, and egoma no ha [Korean perilla] are recommended). Next to the west entrance to Korea Town (closest to Momodani Station) is Miyukimori Tenjingu, a Shinto shrine with a 1,600-year history (see festival info above).

Fading Red Lights, Rising Red Flags

To the east of Tsuruhashi on the Kintetsu line is Imazato Station. A few blocks south of the station is Imazato Shinchi, by far the smallest, most deteriorated, and reportedly cheapest of Osaka’s old-fashioned yukaku (a.k.a. hanamachi) red-light districts, which were sanctioned by officially designating their brothels as restaurants. Imazato was also once an entertainment district of geisha houses and restaurants, frequented by rakugo performers and other luminaries.

The passage of the Anti-Prostitution Law in 1958 necessitated the “restaurant” legal workaround. The most famous of the shinchi (literally “new land”) districts is Nishinari Ward’s Tobita Shinchi (home to approximately 150 establishments), where splendidly attired young women sit in front of grand traditional houses to attract clientele, accompanied by older women who call out to passersby (is this still the case? It’s been a few years since I went through, as a mere observer of course, and it wouldn’t be surprising if Osaka’s ruling party Ishin no Kai were cleaning things up in preparation for the Expo.) In Imazato Shinchi, now home to fewer than 10 establishments, the approach is more discreet, with customers communicating their preferences to a veteran older woman who then coordinates with an okiya lodging house to send a woman who matches the description. Here again I have to thank Joe Vlog, who grew up nearby, for his informative video on the district. Couldn’t have written this without you, Joe!

On a recent visit to Imazato Shinchi, I found a couple of sleepy blocks with what appeared to be the houses in question, with similar white signs hung out front and plaques stating their membership in the local “restaurant” association. It was unclear how much business they were doing, and there was neither a customer nor an older lady to be seen, but it was early yet. On the same blocks, a Little Vietnam of sorts seemed to be more thriving. There are similar Vietnamese enclaves in other neighborhoods historically considered seedy, such as Sakuranomiya in Miyakojima Ward (formerly perhaps the city’s top love hotel district, these days increasingly an ordinary residential area.) On this investigative venture, I felt like I might be seeing the past and future of Osaka encapsulated in a few city blocks. For better or worse, yukaku (with the possible exception of Tobita) are dwindling, and other sketchy aspects of Osaka such as homeless encampments and porno vending machines have disappeared, while Osaka’s immigrant population continues to grow and diversify. There’s no more diverse part of the city than Ikuno Ward, and while its shopping arcades and neighborhoods are perfect for taking a trip down memory lane, new communities are also popping up. Ikuno welcomes strivers from elsewhere, as it always has throughout history.

Why didn’t you include anything about the Deaf school?