Table of Contents

The Immovable One

A rolling stone gathers no moss. By the same token, a stationary stone gathers much moss, especially when splashed with water all day long for several decades. This is especially fitting in the case of a certain stone statue of Fudo Myo-o, a wrathful Buddhist deity (Acala in Sanskrit), as his name literally means “Immovable Lord of Light.” He stands tall, flanked by two stocky acolytes named Seitaka-doshi and Kongara-doshi, at Hozenji Temple in the heart of Osaka’s bustling downtown (in Namba, Chuo Ward near Dotonbori). When not obscured by thick layers of wet moss, Fudo Myo-o wears a fearsome grimace and has a third all-seeing eye, all the better to guard the sacred path of Buddhism and scare believers into staying on the straight and narrow. He holds a demon-slaying sword in one hand and a demon-binding rope in the other, with a tall halo of raging flames at his back.

Hozenji, a Buddhist temple of the Jodo-shu (Pure Land sect), moved from Uji, Kyoto to its current location in 1637. The most widespread school of Buddhism in Japan, Jodo-shu particularly emphasizes reciting nenbutsu (“Namu Amida Butsu,” often translated as “I take refuge in Amida Buddha [Amitābha, whose name translates to “infinite light”]) as the path to rebirth in the Pure Land. The area was home to an execution ground and cemeteries, and for the repose of the departed, monks at the temple did not shirk their chanting duties, performing sennichi nenbutsu (prayers for 1,000 days). This earned the temple the nickname Sennichi-ji and the major avenue in front of it the name Sennichimae-dori (“street in front of Sennichi”), which it retains to this day (see this previous article). But despite its long history, the things for which Hozenji is widely known today – moss-covered statues, warmly lit stone-paved alleys – did not emerge until after World War II, during which air raids burned the surrounding area except for the Fudo Myo-o statue. It wouldn’t be the last time flames licked Hozenji.

Up in Smoke

Hozenji Yokocho (Hozenji Alley) is the collective name of two 80-meter-long, less than 3-meter-wide east-west alleys running parallel to Dotonbori, with the temple at the western end. Rough flagstones, old-fashioned storefronts, and lanterns make the northern alley a sudden and delightful contrast from the hubbub of Minami when you turn into it from Sennichimae Shopping Arcade. In fact, it used to look rather more squalid, and the iconic flagstones are only as old as 1982. Even since then, there have been two fires, including a catastrophic one in 2002 caused by a mishap during post-demolition cleanup of the neighboring Naka-za Theater.

Formerly standing to the north of Hozenji Yokocho, Naka-za opened in 1661 as the kabuki theater Naka no Shibai. In the mid-Edo Period, circa 1800, it was one of five major theaters in the Dotonbori district. It was known for adapting bunraku puppet plays to the kabuki stage, and frequently introduced new plays or staged the Kansai premieres of plays from Edo (present-day Tokyo). In the Edo Period (1603-1868), fires were a regular occurrence (so common in the capital that they were known as “the flowers of Edo”), and Hozenji Temple too burned multiple times. Naka-za, as it was renamed following its purchase by the Shochiku theater group in 1920, remained disaster-prone even in modern times. It burnt in 1928, collapsed due to a typhoon in 1930, and was incinerated by air raids in 1945. The comedy troupe Shochiku Shin-kigeki is a competitor of its better-known Namba-area neighbor Yoshimoto, and Naka-za was the home ground of kings of comedy such as Kanbi Fujiyama and rakugo storytelling legends like Harudanji Katsura III. Naka-za closed in 1999 due to an aging building and dwindling audiences, but even after demolition its curse lingered, with a mistakenly severed gas main starting the aforementioned fire that destroyed the neighboring building and burned down 16 establishments in Hozenji Yokocho. Miraculously, there were no deaths. Today a commercial complex, Naka-za Kuidaore Bldg., stands on its former site.

Mystery of the Missing Stroke

Kanbi Fujiyama (1920-1990) was Shochiku’s top star, a master of aho-yaku (“dumb guy roles”) that earned him the nickname Aho no Kan-chan. The son of an actor, he debuted on stage at age four, and like many child actors he went on to have a troubled adulthood. Evacuated to Manchuria after the Osaka air raids of March 1945, he was captured by the Soviets and spent time as a prisoner of war, then did odd jobs at a cabaret in Harbin, northern China before repatriation in 1947. A founding member of Shochiku Shin-kigeki, Fujiyama never forgot his mother’s advice, during his youth, to party hard because “entertainers who don’t lose their spark.” A regular in the watering holes of Hozenji Yokocho and vicinity, he spared no expense in nights out on the town, once legendarily tipping a bartender by giving him the keys to his car––to keep. Generous to a fault, he often covered younger actors’ debts even when deeply in the hole himself. Unsurprisingly, this made him a sitting duck for unscrupulous acquaintances, and in 1966 he went bankrupt and was fired from Shochiku. After years of scraping by with appearances in Toei yakuza films, Shochiku had to admit that they weren’t drawing the crowds without him, and they welcomed him back and even repaid his debts.

All of this tumultuous history seems encapsulated in the large hanging wooden sign reading “Hozenji Yokocho” which he created for the west entrance of the alley. He wrote the uneven row of characters at their actual size, and famously the kanji 善 (zen, the middle character in 法善寺, Hozenji) is missing one horizontal line (which should be above the square 口 at the bottom). There has been much speculation about the missing stroke. 善 (zen) means “good,” and by his own admission he was “not such a good guy.” When out drinking in the neighborhood, he was likely to say things like “mo ippon taran zo” (“Hey, we need one more bottle”) or “mo ippon tsukete na” (“put one more bottle on my tab,” which might or might not ever be paid). The Japanese counter -hon (also pronounced -bon or -pon, depending on the preceding word) is used for elongated or cylindrical things, which include both liquor bottles and strokes making up kanji, so the above phrases could also mean “it’s missing a stroke” or “you should add one more stroke” respectively. The condition of “one stroke missing” could be phrased as ippon nukete iru, which also means “to have a screw loose,” as Fujiyama would likely have admitted he did. Another theory is that he simply made a mistake.

Let’s Do the Time Warp

At the east end is a similar, more neatly executed sign, also written at full size, by the aforementioned rakugo performer Harudanji Katsura III (1930-2016). Famed as one of the “four heavenly kings” of postwar Kansai rakugo, he was a traditionalist who trained many protégés and kept the solo storytelling genre thriving. He was evidently a well-mannered gentleman, which makes for a lack of anecdotes like those about Fujiyama, and a handwriting analyst might say this comes across in his Hozenji Yokocho sign, which has every stroke in place.

For a trip down the memory lane of the area’s past and its relation to comedy in particular, step into Ukiyo Roji, a dark, even narrower covered alley that connects Hozenji Yokocho with the Dotonbori pedestrian walk. From Dotonbori, enter on the south side between a large Jankara karaoke place and the udon restaurant Imai, incongruously old-fashioned with its willow tree in front amid gaudy surroundings. The walls of the alley are hung with photos, including of the pre-World War II alley and the almost completely flattened Minami (Namba and Shinsaibashi) district after the air raids, as well as old maps and historical info. Another wall of history can be found to the left of the Fudo Myo-o statuary group.

Two Are Better Than One

To the right of the statues is the venerable zenzai (lightly sweet azuki bean soup often topped with mochi rice balls) shop Meoto Zenzai, founded in 1883, after which the Osakan Burai-ha (“Decadent School”) author Sakunosuke Oda named his well-known, oft-adapted 1940 novella. Meoto literally means “husband and wife,” and is often used to describe pairs of things, such as the roped-together rocks offshore near Ise Jingu Shrine in Mie Prefecture. Such inseparability is the theme of Meoto Zenzai, the tale of a shiftless ne’er-do-well and the geisha who keeps on loving him nonetheless. So many old Japanese films and so forth portray no-good louts and the virtuous women who are inexplicably devoted to them, one wonders if it was just a favorite theme for many writers and film directors, or if such couples were really a dime a dozen. For what it’s worth, Oda apparently based the fictional couple on one of his sisters and her husband. In the story, the wastrel Ryukichi spends his time and his common-law wife’s money frequenting cafés and such in and around Hozenji Yokocho. In a bit of dialogue from the novel that hangs on the wall of the eatery, Ryukichi asks his lover Choko if she knows why a certain shop serves each customer two small bowls of zenzai rather than one larger bowl. The answer is that it gives you the illusion of having more, and she comments in charming Osaka dialect, “Hitori yori meoto no ho ga ee iu koto dessharo” [Two together are better than one alone, right?] Of course, Meoto Zenzai serves it up this way to this day.

Alley of Dreams and Dining

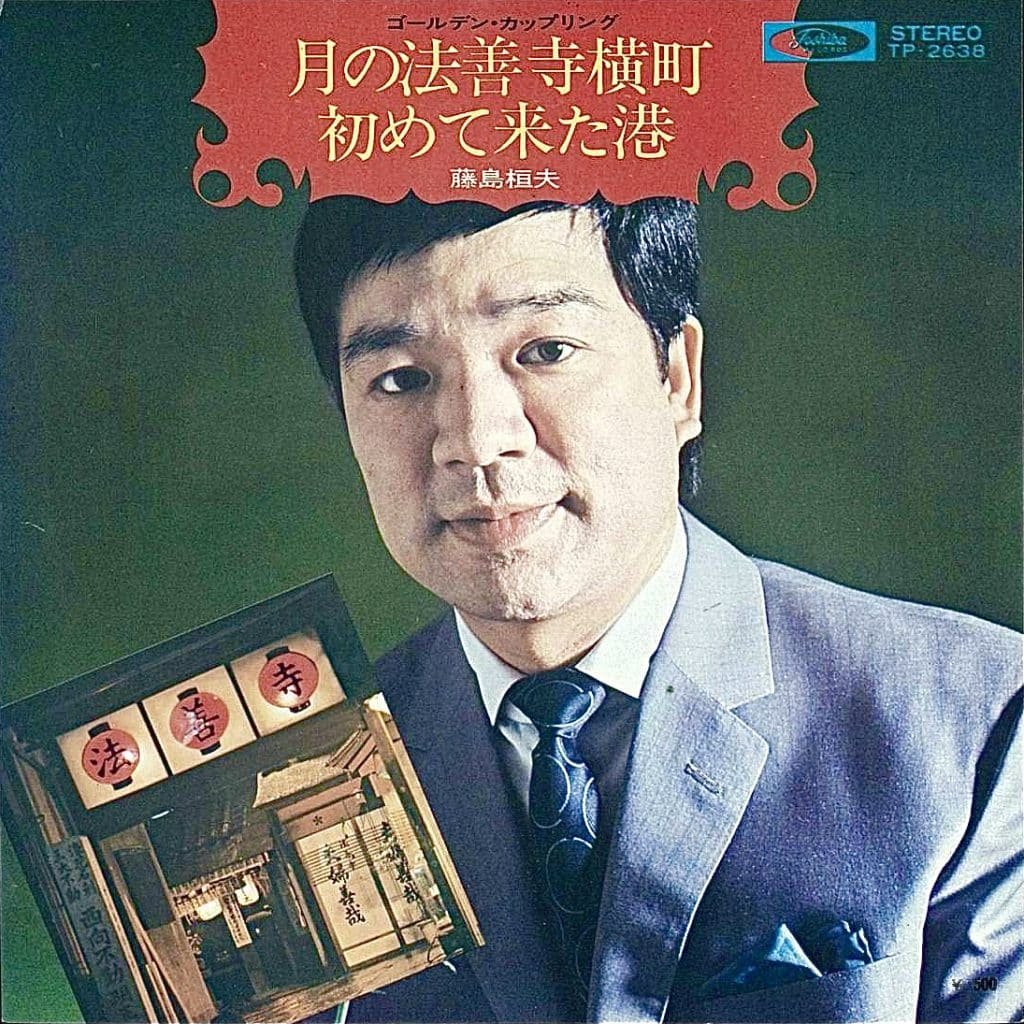

Another cultural touchstone is the popular ballad “Tsuki no Hozenji Yokocho” (Hozenji Yokocho by Moonlight). A hit for Takeo Fujishima (1927-1994) in 1960, it paints a picture of a young aspiring chef saying a sad, hopefully temporary farewell to his love, whose father runs a restaurant where he works. In my rough translation:

(Sung) To wrap his kitchen knife up in a cloth and go off for training – it’s all part of a chef’s journey. Wait for me, Koi-san,* though I know you’re sad. Hozen-ji is full of memories for a young couple. Even the harvest moon, almost full, seems to be yearning.

(Spoken, in old-school Osaka dialect) “Koi-san, the first time you brought me to Hozenji was my first night as an apprentice at [your family’s restaurant] Fujiyoshi. You prayed to Mizukake Fudo for a long time, asking that I become a great chef. That night… I fell for you.”

(Sung) After I perfect my skills and come back to Osaka, we’ll be able to be together. Koi-san, please don’t cry. I’m not good enough for your dad’s great restaurant. Not yet anyway.

(Spoken) “Your dad, the boss, gave his blessing to our desperate love. All that’s left is for me to get good enough in the kitchen. Then I’ll be a true chef. You’ll wait for me, won’t you, Koi-san?”

(Sung) My pride, my love, I bet it all on this knife. I clasp my hands in prayer in front of Mizukake Fudo. Farewell, Koi-san, for a while. Ah, Meoto Zenzai. Hozen-ji, alley of memories. It’s hard to say goodbye. The lights are shimmering.

*Koi-san: Traditional term of address for the youngest daughter of a household, in the Senba kotoba dialogue of Osaka merchants – unless there are four daughters, in which case the third daughter is Koi-san and the fourth is Koikoi-san. Unfortunately, such quaint and arcane lingo is on the wane these days.

Shimmering with tears, no doubt. There probably wasn’t a dry eye in the house when Fujishima performed that one. The lyrics convey Hozenji Yokocho’s reputation as a destination for fine dining, and the restaurants that line the alleys today range from exquisite and pricey traditional kappo ryori to a garish branch of the kushikatsu (fried things on skewers) chain Daruma that looks like it’s invading the alley from the outside world. There are Western-style bars, yakiniku, okonomiyaki, teppanyaki, yakitori, sushi, cafés and more. A bit of research and reservations are recommended for dining, though for drinking you can just drop in, with a possible cover charge. Or you can do what many do and just walk through, see the sights, throw water on the statues and say a prayer. To do it properly, buy a stick of incense and a candle beforehand at the temple office on the left. Light them and stand them in the incense burner and the candle stand, then scoop some water with the dipper and splash away. A common pattern is first to splash the shorter statue of the acolyte on the left, then the one on the right, and finally Fudo Myo-o in the center, aiming for the tops of their heads. For specific wishes, it’s said that the two little guys answer prayers for enmusubi (binding two lovers together) and the birth of children, while aiming for parts of a statue’s body corresponding to ones where you have pain brings healing, and Fudo Myo-o fulfills all wishes. Re-dip if necessary to get your splashing done and then pray away, though there may be a line forming behind you. The moss makes it look like this is an ancient custom, but it too is said to be recent, initiated after World War II by a local woman who regularly visited the shrine.

Two Faces

Only the tops of the acolytes’ heads are bare of moss, from the force of water, making them look monkish. In 2022 they endured the indignity of having all the moss stripped off their heads by a vandal, who after being apprehended told police that the bare patches inspired them to clean off their heads entirely, scraping with the dipper meant for splashing. Now they’re back to their old selves. And through repeated fires, Fudo Myo-o has remained true to his name, immovable. For a hint of its fiery past, visit between 19:00 and 20:30 on the 28th of each month, or do your hatsumode (first shrine or temple visit of the new year) between 14:00 and 19:00 on January 2 and 3, or stop by between 9:00 and 20:00 on Setsubun (February 3), to witness a goma votive fire ritual. Or just swing by any time – it’s open 24 hours a day, befitting the never-sleeping location. Minami is of course one of Osaka’s two major centers of mizu-shobai (literally “the water trade,” encompassing everything from alcohol-related business to entertainment to sex work), and praying at the statue is said to be popular among this cohort due to the “water” connection. Early evening is the most picturesque time to walk the alley, and it’s particularly atmospheric when the flagstones are wet with rain. Bring a visitor to Osaka from abroad here, after taking in the bright lights and moving signs of Dotonbori, and you’ll have shown them the two most dramatically contrasting faces of the city you can see in five minutes’ time.

I always wondered about this moss-covered relic! Thanks for the informative piece! Very illuminating!

Colin! Excellent peice! I took my cousins thru here some years ago Not really knowing what the history was but because I live here by default I suppose I seem to know what it means but I also wanted to know I have stopped by the prayer area where you gift coins and done it as one would anywhere it’s been without really knowing the story.. illuminating thanks bud! Nice meeting you at our writers meet up although I believe we met as well years before ! Wes Wesson