Over the last one hundred years Shiitake, or ‘poor man’s matsutake’ have taken first place in the world of edible Japanese mushrooms. Shiitake have a thick, wide cap from two to five inches in width. The caps are of a light cream to chocolate brown color contrasting with their pale undersides and off-white stems. Known as the ‘fragrant mushroom’, they are best known for the earthy, woody taste they impart to dishes in tandem with a steak-like toothiness making them a perfect substitute for meat. Often used in soups, hot pots, steamed, grilled, or fried, monks of the Zen sect found long ago that forest grown shiitake best enhance other flavors of shorin-ryori, temple food, better known as vegetarian cuisine. It is often served in izakaya.

Today, in our ever-enlightened state of Umami, we know that shiitake contain a natural occurring chemical compound called Guanylate. This unique compound contains super umami-boosting properties that interact with the glutamates contained in nearly all foods. The process by which they interact seem to enhance other foods’ potential such that every ingredient creates an exquisite symphony of flavor.

Sold fresh or dried, the latter possessing the most concentrated umami, both play different roles in Japanese cuisine. In recent years, shiitake mushrooms have expanded their culinary roles not just in Asian cuisine, but in Russian and European cuisine as well. In Osaka’s vast Izakaya (Japanese style pubs) nightlife, this humble food is a major hit, pairing well with drink, otsumami (finger foods paired with drink), and other dishes.

This article will explore the history of fungi in Japan, the rise to fame and popularity of shiitake, the world’s second largely exported mushroom, and a few secrets on how to source, pick, or grow your own for your very own table. Before we dive into all thing’s shiitake, feel free to scroll closer to the bottom for a few great izakaya to access and even a few great recipes to try for yourself!

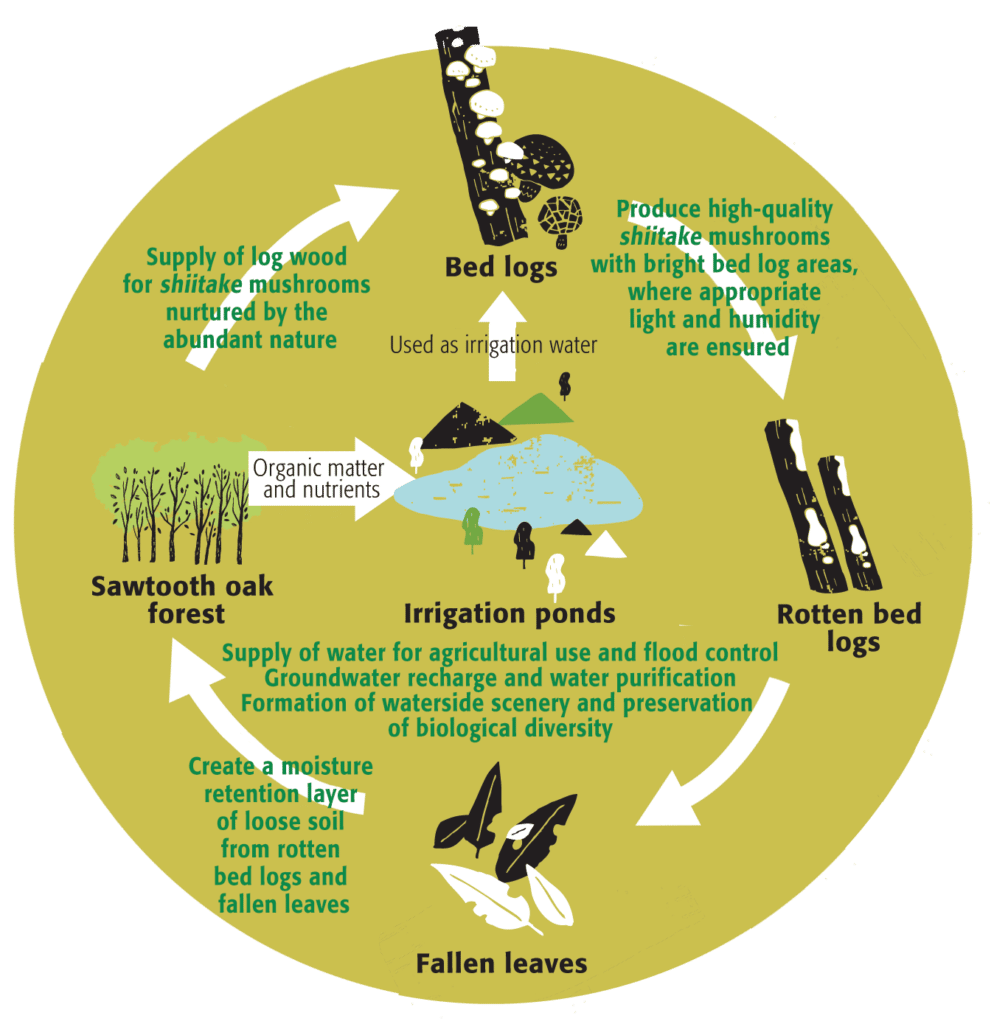

(Photo credit: gov-online.go.jp.english archives)

Table of Contents

A Hated Favorite

As a child, if most of us had ten friends, nine out of ten on average loathed mushrooms! If you were like me and had parents like mine, yours couldn’t buy, beg, borrow, or steal a single trick in the book to lure you into mushrooms, no matter how well prepared, nor cleverly concealed!

My mother’s late autumn “go-to meal” was steak coated in mushroom sauce. We either raised our own beef or had it raised for us in those days but alas, all my mother knew was a broiler. My father’s lament was well known: “She can kill a steak twice!” She found that she could levy the balance by whipping up a thick, brown sauce with mushrooms and French onion. My father’s complaints quelled; my earliest memories are being kept long hours at the table “Until you eat every bit of that!” To this day, a steak thrown upon a plate like boot leather holds absolutely zero appeal for me.

As for mushrooms, these days it’s a different story! Those ten friends if interviewed today? We might find seven of the ten- on average- have turned in favor of mushrooms. Somehow into adulthood somebody had worked their culinary magic and changed the minds and tastes of those of us dead set against mushrooms!

Born Again

For me, it was Wyoming at age twenty-two. Just back from a long tour in Japan and newly appointed to Francis E. Warren Airbase, I was introduced to a Chief Master Sergeant in my section living in the pine-forested hills northwest of Laramie.

He and his Japanese wife, Setsuko, and her network of other Japanese and Korean wives were avid matsutake, or pine mushroom, hobbyists. They would find, collect, slice, dry, and package the highly aromatic matsutake for sale overseas in Japan and Korea. One large-sized, densely packed coffee tin would bring $1000.00 U.S.! Before long, I would be invited to bivouac with three other families on their annual hunt!

Being peak season in late October, we hunted and picked wild matsutake nonstop for three days in miles of forested backland inhabited only by the wild. “Either we get them first, or the deer and bear get them,” beamed Setsuko.

She taught me how to detect a slight rise in the pine needle bed under the trees, how to work it from its soil bed without breaking, how to smell test for a slight pine varnish scent to insure it was genuine. Often one will find an odorless, poisonous imposter within the same bed. “No smell, no go!” she’d say. We would bend, dig, pick, smell, and fill our leather pouches. Then moving slowly, repeat the process, ever crouching over the landscape.

When we dragged our haul back to camp, I was treated to the delightful taste of these fresh-sliced matsutake fried in butter and a few shards of wild garlic. Nothing from the fungi world I’d ever had up to that point has come so close to heaven. I was a convert!

What are Fungi?

Are mushrooms a plant? An animal? That’s a tricky question! They don’t have leaves, flowers, seeds, nor do they produce any fruit! What can we call these then? Fungi!! Fungi rate as a kingdom all of their own! With the inability to ingest food and convert that to energy as animals do, and lacking the ability for photosynthesis which plants use to convert sun energy to food, fungi are a considered a group. This group consists of yeasts, molds and mushrooms by which spores coat a substrate such as tree bark or decaying matter such as tree trunks, fallen trees, and cut logs.

These spores send out mycelium- a network of threadlike roots that penetrate and spread throughout the substrate and often the entire forest floor. This rooting cell system finds its nutrition in its host. Mushrooms are simply the ‘fruiting body’ as well as spore-shedding reproduction system of rooting mycelium. Fungi, including mushrooms, are responsible for an important part of the ‘decomposition’ stage within the eco system cycle.

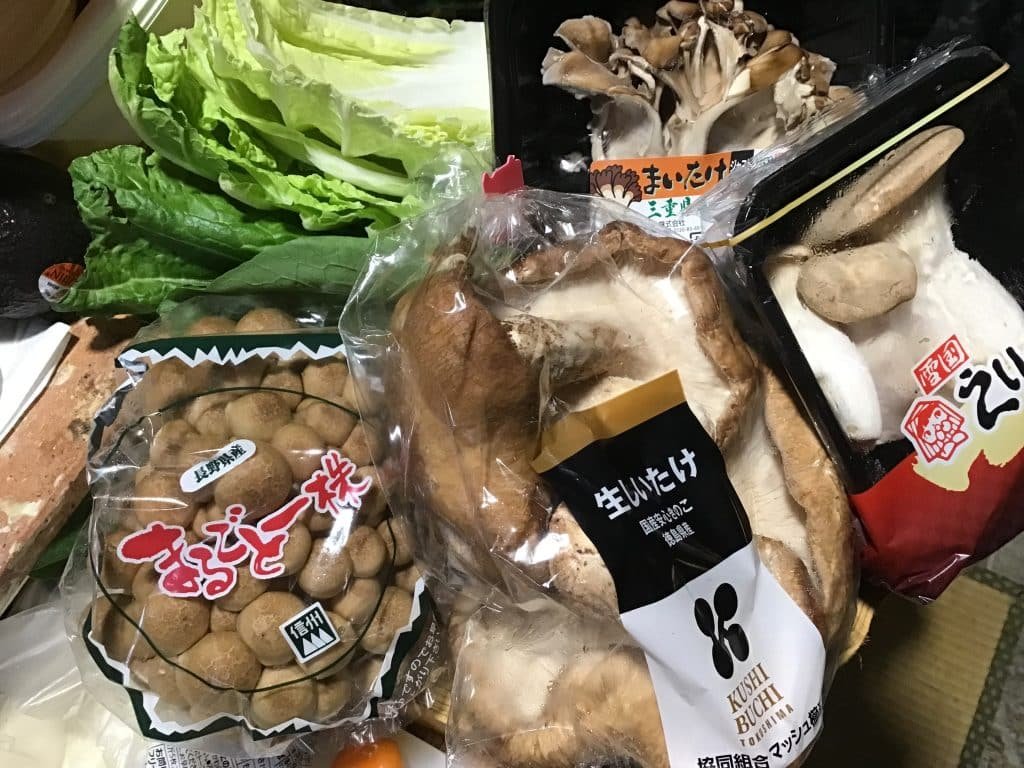

Japan is home to over 5,000 varieties of mushrooms, 100 of which are edible. Of this 100, there are around 10 average species sold seasonally or for year-round sale: maitake, bunashimeji, enoki, hiratake, eringi, nameko, kikurage, white (button) mushroom, shiitake and matsutake.

Japan’s Long History with Fungi

Since ancient times, various types of fungi have been regarded as an integral part of the autumnal bounty in Japan. Mushrooms have been a staple of culinary applications and revered for medicinal, ritualistic, and existential purposes. Commonly called kinoko or take/dake depending on the substrate they grow upon, (Take grow upon the forest floor. Kinoko can only grow on trees.) these fungi have a long-recorded and varied history throughout Japan.

Excavated pottery and earthenware castings of mushrooms dating as far back as the prehistoric late Jomon Period (3,000 – 2400 BCE) show evidence of the widespread ritual use and worship of mushrooms, particularly kinoko. Earthenware mushroom imitations made from clay were unearthed in the Ise-Dotai ruins of Akita prefecture dating back to 2000 BC.

While it seems clear the attitude of reverence held by the people of the Jomon period for mushrooms, there is no singular timeline recording mushrooms as a familiar food source. Haiku written about Japanese mushrooms (along with Tanka pictographs of 7th century aristocrats on Mt. Takaen in Nara, mushroom hunting) are found within the Man’yoshu, or “The Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves”. This famous manuscript is the oldest known existing anthology of Japanese poetry and literature from the Nara Period, 8th century. It has other direct references to mushrooms.

In “The Collection of Gleanings of Japanese Poetry”, the Shui- Wakashu, both matsutake and hiratake were not only consumed as special food at banquets, but often given as gifts or souvenirs, obviously both prized edibles in the Heian Period.

The 11th century folktale collection, “Tales of Long Ago”, Konjaku Monogatari, recalls a story of a group of forest-bound woodcutters who happen upon a group of Buddhist nuns singing and dancing through the depths of the forest. They confessed they had eaten maitake, [mai,” dance”; take, “mushroom”] an account that alludes to the psychoactive properties of certain mushrooms. The nuns shared some with the wood cutters who themselves could not resist dancing and singing!

In the Edo period cookbook, “This Breakfast Guide”, a document meant to ‘spread the awareness handed down by our ancestors’, praised seven main mushrooms: matsutake, maitake, hiratake, enokitake, shiitake, kotake, and shoro, or “false truffles”. Cooking methods mentioned reveal that in any era, the method of cooking mushrooms was mainly soup, simmered hot-pots, fried food, and grilled food. While there is no definitive clue as to just when mushroom consumption began in Japan, it is generally believed that consumption began around 3-4,000 years ago, while mass cultivation began around 400 years ago in the Edo Period (1603- 1838).

Early Consumption: Mushrooms Over Meat

Edible mushrooms have been valued worldwide since the earliest part of human history. The Greeks believed soldiers readying for battle were strengthened by mushrooms. Romans believed mushrooms to be the “Food of the Gods.” Chinese culture has hailed them as “The elixir of life.”

Today, mushrooms are considered a powerhouse of healthy, cholesterol and fat-free, nutritional benefits. They are low in calories, carbohydrates, sodium, and fat, yet rich in an abundance of vitamin D, potassium, selenium, niacin, riboflavin, proteins, and fiber. Many other nutraceutical properties found in mushrooms are extolled for their healing and medicinal benefits as well as prevention or treatment of Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, hypertension, and risk of stroke.

In the ninth century, Japanese emperor Saga passed a law against the killing of animals and the consumption of their meat (aside only from fish and certain fowl). Thanks to the nutrient rich, umami packed, and almost meaty texture, many mushrooms became a delectable substitute- and have remained a savory addition to Japanese cuisine ever since. Valued for their fragrance, woodsy flavor and texture, mushrooms are known as one of the main umami ingredients of the vegetarian, Buddhist-inspired ‘enlightened diet’ or keihatsu sareta shokuji. Many types of mushrooms are a main ingredient of vegetarian shojin-ryori, known in the early days simply as ‘temple food’ before vegetarian food was a revered class of its own.

“Hush, hush! Never tell the secret places you find your mushrooms, not even to your own son!”

-A Japanese Proverb.

Cultivation of Take

So precious are forest floor mushrooms, this old Japanese saying admonishes farmer’s foraging wives to keep them secret! In years past, most edible mushrooms in Japan were available only in autumn and collected by hand. Many varieties not growing on trees were collected from the forest floor or fallen, decaying matter.

Over the last 200 years, though mushrooms are still sought out by avid collectors, artificial cultivation has taken the place of foraging. Through trial and error, processes of elimination, setbacks and successes, farmers began to realize the ability to grow their own mycelium roots by mimicking substrate from the forest floor.

Grown upon substrate such as tree shavings, nutrient infused saw dust, wet, dichotomous organic matter, and dry matter such as rice bran, buckwheat, grain, foxtails, hay, and so on, this process spawned the original bacterial bed cultivation- for growing take. This substrate is often set up upon thatched shelves and stacked upon each other like bunk beds.

Artificial cultivation of mushrooms using techniques that mimic their natural environment, is the sole reason the mushroom industry exists in such hiatus today. It has kept many breeds intact, while spawning many more. Mating of monokaryotic mycelia by a process called hyphal fusion has become the typical method to breed new strains of mushrooms. This allows farmers to capitalize on mushrooms size, color, and abundance.

Many types of popular mushrooms are now available for year-round sale thanks to such cultivation techniques. Bumper crops have ensued with farmers making available for domestic export the year round the ‘top eight’ mushrooms commonly sold: bunashimeji, enoki, hiratake, eringi, nameko, kikurage, and–last but not least- shiitake.

Let’s talk Shiitake!

In modern day Japan, the king of the winter season -if we push matsutake aside – is shiitake (Lentinula Edodes), ‘Fragrant mushroom’ of the deciduous bark of the Shii (Castaneoideae) tree -thus its name-and other hardwood trees such as hornbeam, chestnut, saw-tooth oak, poplar, and other chinquapins. Shiitake grow in clusters. Native to East Asia, the shiitake is the second most cultivated fungi in the world after button mushrooms, (white mushrooms).

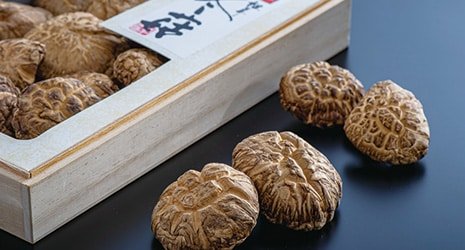

Hailed as ‘The poor man’s matsutake,’ shiitake vary from light to chocolate-brown contrasting with their pale under caps. The stems are a cream to off-white color, often with a furry, fibrous mycelium membrane as the nights grow colder. Also, with the cold end of season, they develop a creased tortoiseshell top – prized for its design in culinary dishes.

A true kinoko, shiitake are unique in that they are unable to grow upon the ground. Forest-grown shiitake naturally harvested come in various shapes and are named by grade. Donko and Koshin shiitake are the main type sold throughout Japan. These are harvested from the same type of shiitake but each at different timing of maturity. Shiitake picked at the height of their individual season at different stages of the umbrella cap closed or just opening are the most desired for their very concentrated medicinal and umami properties.

Donko therefore refers to shiitake gathered before the mushroom can fully open up and bloom. Donko is thicker, chewier, and has a deeper, meatier aroma but much smaller in size and appearance than Koshin. Koshin has a more brilliant fragrance, but has a larger, flatter umbrella. As a general classification, less than 70% of shiitake umbrellas open or bloomed are donko while greater than 70% are koshin. The most superior on the grading scale are the very small, closed capped nami-nami donko. These donko naturally fetch the highest price on the market.

The word “donko” comes from the Chinese word for “winter” harvested mushrooms. Forest-grown shiitake are harvested twice a year: spring and fall, at times two to three times per season. However, donko gathered mainly (mixed with koshin) from December to April, having grown through the cold months make these true winter mushrooms. On the other hand, the autumn harvest produces a few donko, and most are koshin. The larger koshin harvest is due to the higher temperatures, which mature the mushrooms more quickly, making them larger. Today, this process is extended into winter by cultivating them inside warmer tents.

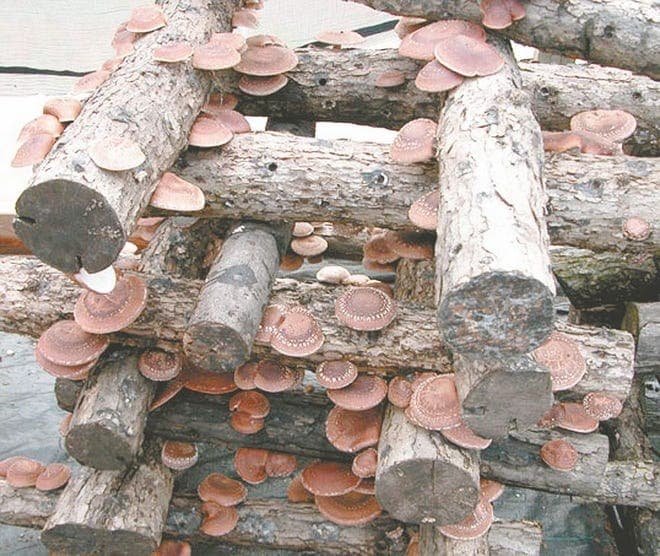

The history of shiitake mushroom cultivation is said to have started as recently as 400 years ago during the Edo period. Believed that spores dropped and proliferated from mature clusters of shiitake, new cultivars were produced by placing rotting timbers next to fallen, decaying trees with known populations of existing shiitake. Farmers also cut limbs and logs, placing them against producing trees to catch the fallen spores.

Records of first mass cultivation began with the famous story of Gembei in Bungo province in Oita prefecture. Gembei was an old farmer who baked limbs and logs of trees over fire to make and sell charcoal. He discovered shiitake growing wild within ruts and crags upon his stored charcoal. Realizing it must be wind that placed millions -if not billions -of spores along a broader range, he asked himself, “What if shiitake could be produced artificially?”

(Photo credit: gov-online.jp)

Genbei used a “scratch method” whereby many scratches and wedges were sawn or cut into the bark of cut logs, stacked together to “catch” spores. Imagine Gembei’s surprise at his newly sprouted crop within a mere few years! This turning of the tide was the birthplace of mass, artificial production of tree borne kinoko such as shiitake.

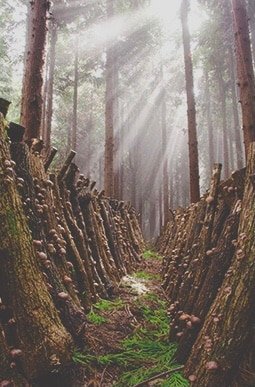

As word spread faster than spores, farmers near and far mimicked Genbei’s techniques. Cultivation tripled and with it, advances in cultivation techniques. Over the next few hundred years, specially cleared areas of forest called Hodaba evolved. The hodaba was usually placed under or around trees or fallen trees that produced shiitake. Logs of Japanese saw-tooth oak or other hard wood varieties were set against horizontally raised poles called Hodagi within each Hodaba. These logs were scored or pitted with holes or hatchet creases creating a sort of ‘ledge’ for potential kinoko to grow upon. Spores thereby would spread to those surfaces and proliferate.

Photo credit: Shiitake-Himeno.com

The hodaba is still the preferred method of cultivation today producing the most prized shiitake born in a natural environment of light, air, and humidity. After an incubation period of 1~2 years, mushrooms are produced for 4-6 years, usually with a single harvest in spring, and a double harvest in fall. Logs are recycled and replaced with nutrient rich logs at the end of each cycle. Not much has changed in the past hundred years except the method by which spores make their way into logs or other substrate.

Inoculation: From Axe to Drill

Spore catching techniques since the old days remained somewhat unpredictable until 1943 when Kisaku Mori, an agricultural student from Kyoto University, developed a highly successful method. In the Mori technique, the fungus was grown on pre-sterilized wood chips. The chips were covered with a pure culture of the fungus then used as inoculum by placing them directly into axe cuts or into holes drilled into logs.

Today, prepackaged inoculated inserts abound. Drilling nearly fifty holes per log, professionals use a handheld hammer slotter to insert a ‘spawn plug’. When hit in the back, this instrument slots the shot of inoculated spawn plugs perfectly in each hole. The logs last about 3-4 years before running their course and are stacked for recycling.

(Photo credit: gov-online.go.jp.english archives)

Modern Day Export

Shiitake both fresh and dried are the major edible mushroom in Japan and have been since the early 1930`s. Prewar records dating back to 1935 indicate that a whole 2000 tons were being exported in that year and every year up to 1940. A natural lull in production and export occurred in Japan during war-torn years 1941~ 1945 but by 1949 they were back up to around 1000 tons production and up to 1400 tons by 1950. Skip forward 28 years to 1978, the industry employed 188,000 people, exported 10,000 tons, and generated $1.1 billion in retail sales. Dried shiitake became Japan’s major agricultural export.

Japan’s exports were highly prized through the seventies and late eighties however, wholesale exports from Chinese markets began to dominate in the nineties with prices far below average. Japanese companies on the international exchange have become fewer since. Lucky for us here in Osaka and throughout Japan, a booming domestic market still thrives!

These days the mushroom industry is run by a handful of small farms and more than a handful of large conglomerates such as Oita prefecture’s OSK. These companies mass produce by shelving vast beds of mushrooms or cube substrate of kinoko upon multi-tiered shelves. These are equipped with misters and temperature control devices. About all the professionals must do is watch them grow and pick them at just the right time!

Pick your own in Osaka!

While a wide array of mushrooms is found in abundance at any supermarket or roadside farmers markets in Osaka, for those of you wishing to pick your own, we have good news! There are two farms within about an hour of each other that both offer picking opportunities to the general public!

Takatsuki, Osaka: Takatsuki Shiitake Mushroom Center

In the hill country north of Osaka Kita Ku, Takatsuki City’s Shirin Kanko Center houses a fairly spacious shiitake farm.

Visitors can learn about shiitake, pick their own (100g for ¥300), and either take home or opt to barbecue them at the

restaurant located within the center. A great day trip for kids!

- Location: 〒 569-1002 Takatsuki Shinrin Kanko Center, 2 Oazatano, Koazamatodani , Takatsuki-shi, Osaka

- Tel.: 072-688-9359

- Hours: Open weekdays 10:00-15:00 except Tuesdays (unless a national holiday falls on Teusday), New Year’s holidays (12/27 – 1/5), and weekends 10:00-16:00.

- Parking available.

- Directions: Located a 5-minute walk from Shinrin Senta-mae bus stop via city bus from Takatsuki Station on the JR Kyoto Line

- URL: https://www.kinokos.net/

Mino City’s Todoromi; Kawanishi-En Orchard

“A region of vast and rich nature”, Kawanishi- En Gardens encourages visitors to try potato digging and shiitake.

picking on their own! The park boasts a spacious BBQ area where supplies can be rented, or you can bring your own to

grill what you pick.

- Location: 563-0251 492 Todoromi, Mino, Osaka

- Tel.: 072-739-0609

- Hours: Weekends ONLY 10:00-1600.

- Parking: Available.

- RESERVATIONS: Necessary only for shiitake picking. Please reserve three days in advance!

- Directions: Kaminosho bus stop via Hankyu bus from Ikeda Station on the Hankyu railway.

D.I.Y.’ers Grow Your Own!

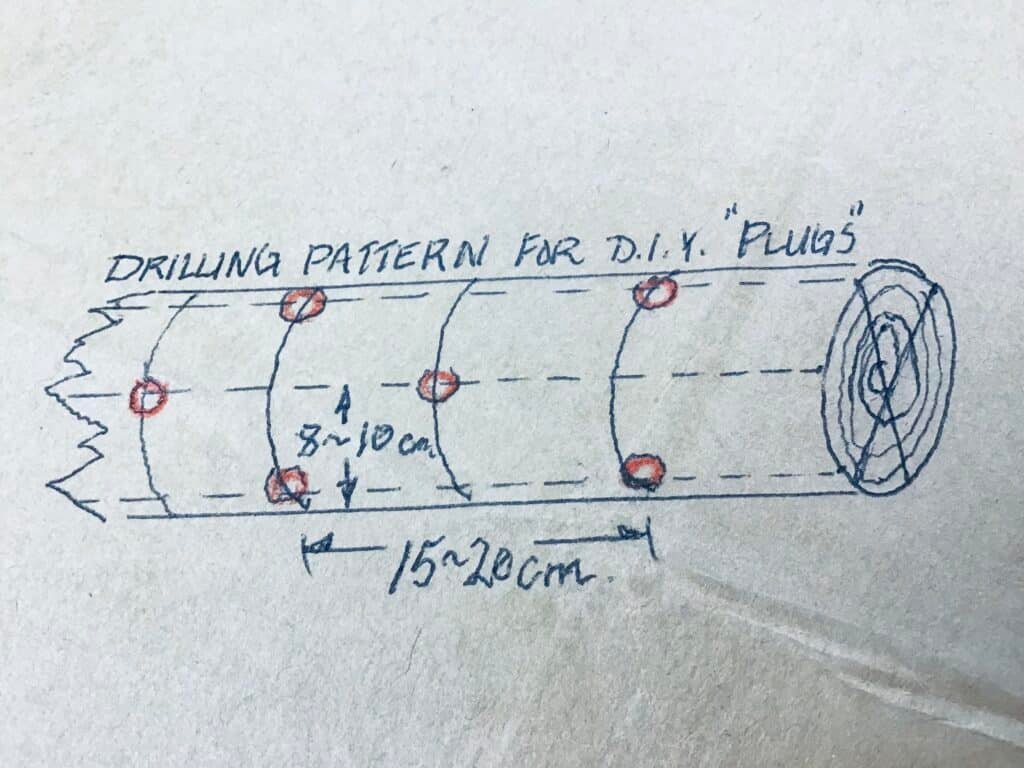

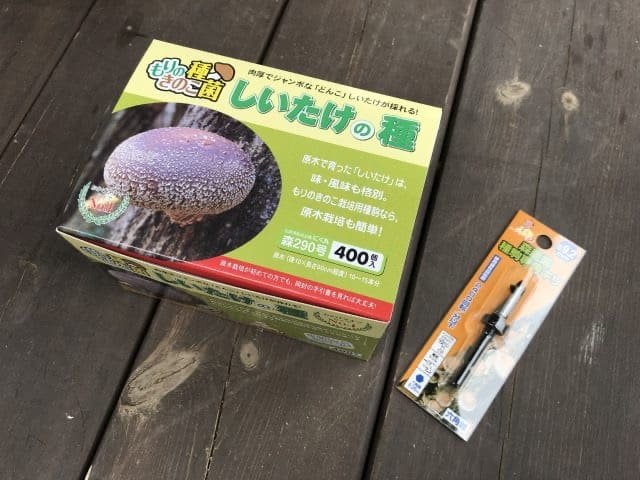

For those of a DIY nature into shiitake and other mushrooms, you too can create your own hodaba! To purchase or cut your own logs, run down to the nearby home center or order online, cut logs (pre-drilled or drill-your-own- the former a bit pricier), a package of pre-inoculated cork or sponge ‘plugs’, drill your holes and push the plugs in! Your author started his own hodaba nearly 16 years ago. Various types of tree- borne kinoko can be grown with plugs.

(Photo credit: o-ism.com)

For the bacterial bed enthusiast, a wide variety are able to be grown at home. These too can be done at home by the beginner home grower. Homemade substrate using things such as ground sesame and buckwheat, rice bran, a dark organic soil mulch, and a binder. Instead of putting these in a bed or shelf form, you can grow them simply in plastic-lined recycled foam ramen cups! Or better, buy the mixed substrate as seen below in bag or box form, add water, let it do its thing! Instructions are provided stipulating just how many days or weeks you will begin to see mushrooms.

Try these video links below to see more on this process: the first video is Day 1~2, the second is Day 3~7. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIQltqP17Cc

【アメリカ生活~栽培編】マッシュルーム栽培 Day2~Mushroom Grow Kit – YouTube

(Photo credit: O-ism.com)

Run, Don’t Walk! Four Restaurants Serving up Delicious Shiitake Dishes in Osaka

Choosing four izakaya Japanese style pubs, from far north Osaka, up town, middle-south town, and far (deep) south, we were curious as to how the menus by area might differ in size, preparation, presentation, and flavor. As simply divine as shiitake truly are, let’s just say we were pleasantly surprised. While there are countless ways to prepare these, we found that anywhere we chose to go, either pan fried, grilled, or deep fried was the holy grail when paired with drink. And come on, who doesn’t enjoy a hot fry-up with a cold beer? While the methods of cooking these shiitake were close to the same, on a micro level, looked at closely through the glass, each indeed differed and represented a variety of possibilities, fusion, and flavor within the frying/grilling game.

IZAKAYA: Awaya (JR Awaji) あわや

Address: 4 Chome-33-22 Higashiawaji, Higashiyodogawa Ward, Osaka, 533-0023.

Tel:06-6160-0050. Open: Mon-Fri 13:00-21:00; Sat, Sun: 12:00-21:00.

The train station in northern Osaka’s Awaji sits high upon her ground, a stone fortress in the clouds. When you jump out the gate from Awaji’s raised platform, take the steps down. If on the west side, tunnel under the bridge to the east side, back up to the road, you’ll find the east-side arcade running north to south. Travel north until the arcade plays out within two blocks or so, hook a right. Go to the main road hook another right, walk down 100 meters and Awaji’s gem, AWAYA is waiting to welcome you.

Nobuyuki Tanaka, proprietor, set this shop up with his private network a few years back. The newest and hottest watering hole in Awaji, Awaya is an extension of the izakaya he worked at for years in Tenma:Ginzaya. Flowing white beard, hair tied back, buttoned into a suit vest and oshare, stylish sleeves, the cook is in his kitchen!

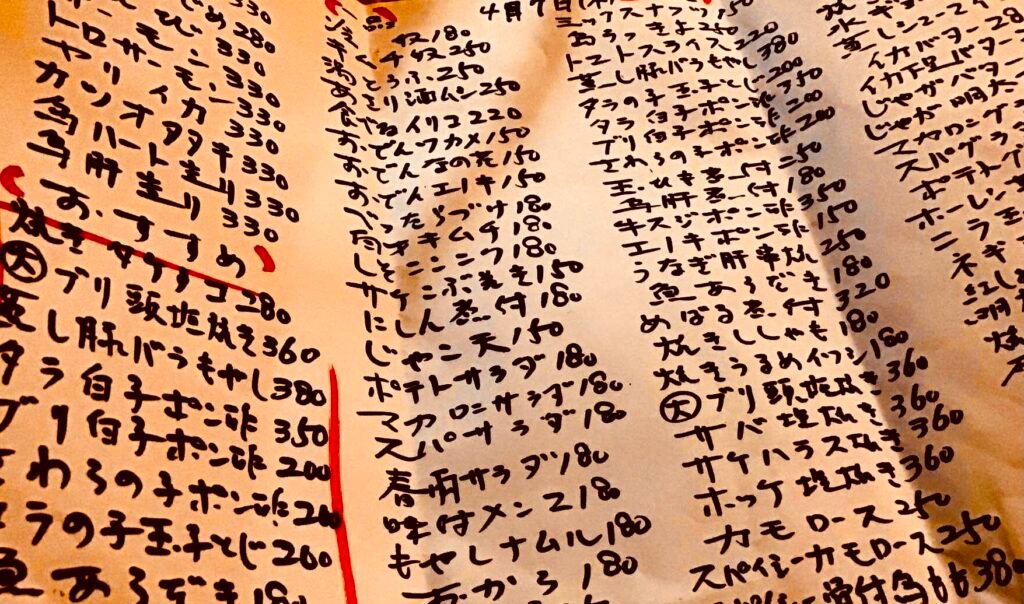

All menus are meticulously hand-written, with over 100 different options to choose from, the food cooked to perfection, and the beers ice cold on tap. Tanaka-San was a part of the free spirit movement in the sixties and travelled extensively on Route 66 in his twenties. With a very able grasp on English, a ready smile, and an amicable, welcoming air about him, Tanaka-San is the epitome of an OLD SHOWA MASTER in any izakaya, to say the least of his own, AWAYA.

Tanaka-San welcomed us to come up and try his different approach to shiitake. Enthusiastically obliging, we hopped on the Metro from Tengachaya,(K20) on the (K) Sakai Suji Line. In no time at all we were passing Tenjinbashisuji 6-chome (K11), the point past which the subway becomes a regular train operating on the Hankyu Kyoto Line. From there, Awaji is a mere two stops and only costs an additional fifty yen to adjust your ticket upon exit.

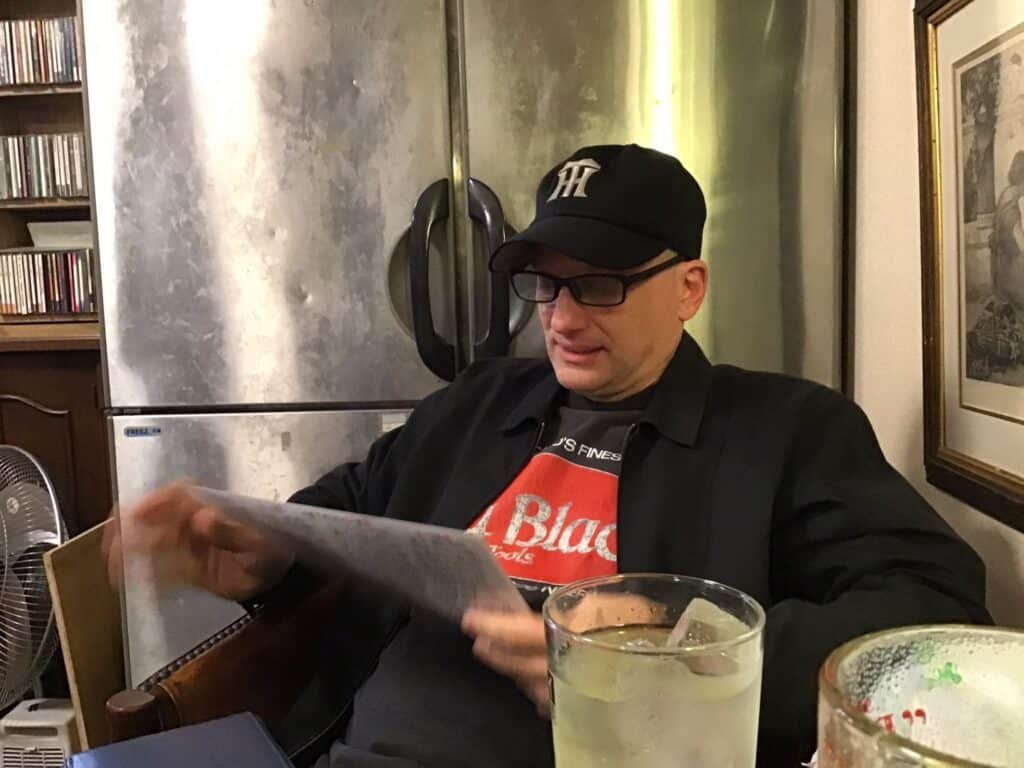

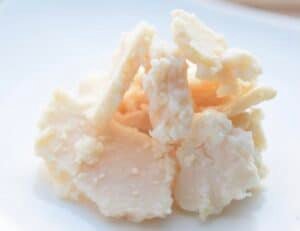

Tanaka-San was in fine form with a full place. We enjoyed drinks with other patrons and waited for our shiitake surprise. Tanaka-San wouldn’t let us see them until he handed the dish over the counter – what you see in the picture is what we saw. I gave a start because they were not the medium to large size we’d been hunting! They were so small I thought they were escargots! “Wow, Tanaka-San! What in the world of fungi are these?!”

“Here at Awaya, and anywhere in KITA (Northern Osaka~<onset> Kyoto) we prize the small over the large,” Tanaka replies, a grin spread ear to ear. “They MUST be small, barely opened and they MUST be tempura! There is no other way we prefer to eat these, no better way to enjoy the earthy goodness of these small prizes. There is no other way we would consider them better than THIS! Crisp outside, soft and flavorful inside, our take on heaven! that’s how we do these. Eat up! Eat them hot!”

True to his word, they were a delightful take on shiitake. Extremely earthy, woody, intensely aromatic, the tops brittle and crispy, the insides so soft and hot enough to melt on your tongue! Tanaka’s batter is a handmade tempura batter with cornstarch, making a light batter coating and a crispy, delicate finish. Exquisite! A very gourmet play on these, I emphatically recommend these with a mug of sake or hot, oyuwari shochu. Thank you, Tanaka-San! We’re definitely coming back for more!

IZAKAYA: Azuki Iro no Marcus, Temma あずき色のマーカス

Address: 4 Chome-12-11 Tenjinbashi, Kita Ward, Osaka, 530-0041. Tel. N/A. Open: 15:30-24:00 (L.O. drinks 23:00), daily. Closed New Year.

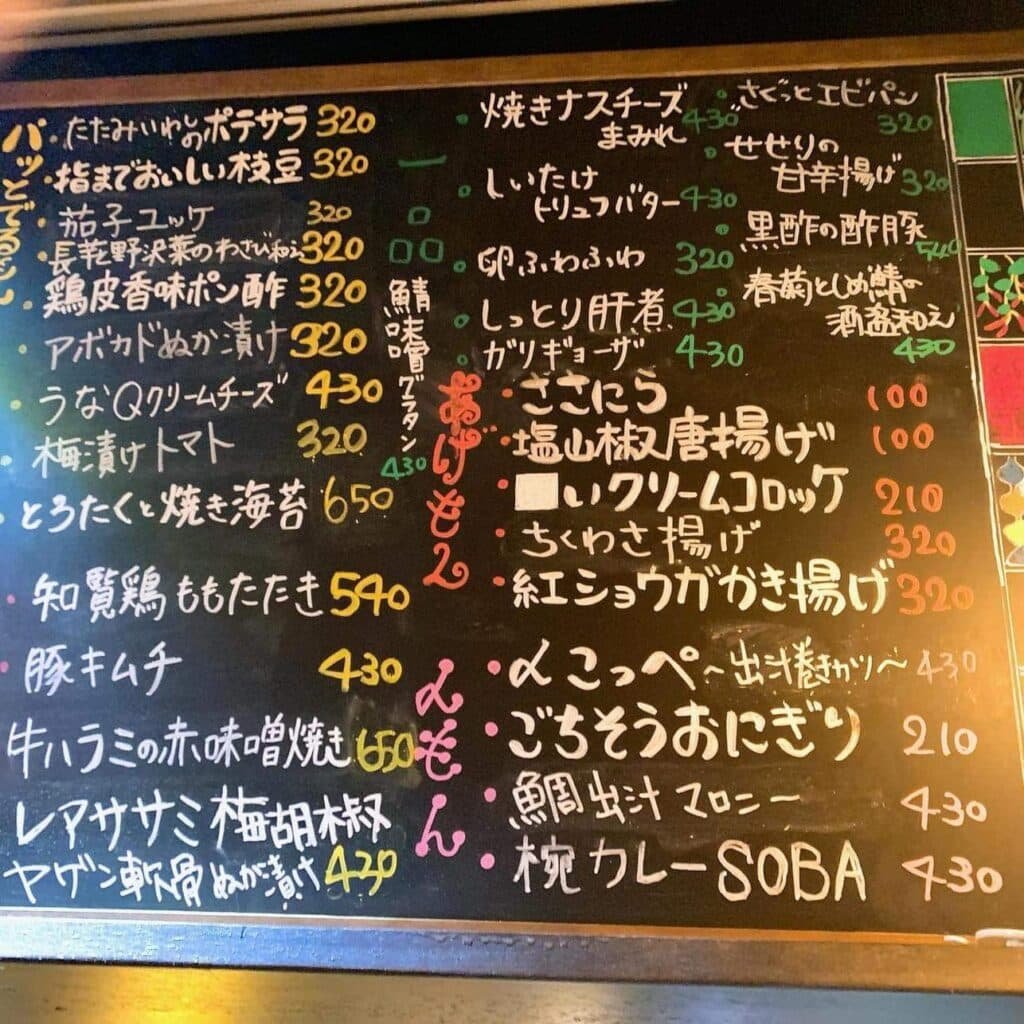

Duck into the shotengai, arcade, in Temma for the best kept secret since Grandma’s apple pie! Azuki No Iro Marcus awaits you!

Many standing bar izakaya are known to have a simple, hard, blue collar, working man’s vibe that seem to yell out over the crowd, “Step off the moving cars for one at our place! Lay your worries aside, and your money down! HERE is where you can forget about the grind for a time, step up to the counter, boys! Wash thine troubles away!” Traditionally, the izakaya has been a working man’s world. Azuki Iro no Marcus proves otherwise; this restaurant is very popular with women of all ages. An ‘F’ for ‘free’, one size fits all, Team Marcus has something everyone seems to love.

Says one male reviewer on Tabelog: “My date and I went into Marcus on a whim. Seeing ‘standing bar’ on the sign, I entered hesitantly only to be pleasantly surprised. The place was nicely decorated and full of a younger female crowd enjoying the tradition of standing bar as if they were born to it! One side of the menu was totally dedicated to sake. Brands from all over the country! Right up our alley! I tried one from the hometown of the woman I was with, Nagasaki, and was very pleased. The menu was beautifully prepared and reasonable. The dishes were delicious, and the drinks were like home. The atmosphere seemed to be a great place for women who might be trying standing bars for their first time. Besides, my date and I could thoroughly enjoy sake paired with exquisitely prepared dishes, not so huge in volume but packing a big punch in taste. I love Marcus!”

Known around the town and well versed on all things Osaka nightlife, Tatsuya “Tats” Inaoka originally put Azuki Iro no Marcus on our radar. “You’ve got to try that place! We were just there, we ordered the shiitake mushrooms with cheese,” says Tats, an Izakaya standing bar enthusiast since the late seventies. “I like them a lot. It seems that Marcus is famous for their mackerel saba sandwich however, I’ve never tried it. At least, not yet! As you know, Japanese people like glutamic acid. I’m one of them. That [ingredient] is included in shiitake mushroom a lot. And it goes well with soy sauce and cheese. All Osaka people love such kind of dishes.”

In the beginning of March, my friends Matt, Jake and I decided to take Tatsuya’s advice and hit Azuki no Marcus for ourselves to celebrate our friend Mike’s birthday. Within about 150 meters we found the front door to Marcus down a rock paved path just off the main arcade. The place was packed! After a short wait, were offered the best standing ‘seats’ in the whole house! An old, refurbished hutch from times past around which four grown men could stand and enjoy their very own waist high “bar”!

Throughout the night, upon that countertop, bottles of Sapporo Black Star beer and plate after plate of some of the finest offerings were placed and quickly devoured. Of particular interest was their 100- yen feature: a champagne flute housing sprigs of Japanese mustard leaf, komatsuna, served with a thimble of spiced olive oil and herb.

The place was packed with a fun loving, jovial crowd, both male, female, and quite a few couples. The retro style of the place in tandem with old refurbished Japanese furniture had Mike saying, “Now THIS is a place I like!”

The very first dish we ordered and savored most was the very same shiitake dish Tatsuya had told us we had to try! In one word? AMAZING! Pan steam- fried in sake, ponzu citrus soy, truffle butter, glutamic acid, quartered and tossed in the pan again, plated and garnished in grated shards of parmesan, the shiitake are a perfect pairing with a sweet, smooth glass of sake or an ice-cold tankard of ale! Thoroughly impressed, we will be seeing more of Azuki Iro no Marcus real soon!

IZAKAYA: Hige to Boin, Taisho 大正サロン髭とボヰン

Address: 1 Chome-5-14 Sangenyahigashi, Taisho Ward, Osaka, 551-0002.

Tel; N/A Open: Every day 15:00-24:00.

(A thirty second walk from Taisho station west exit, north side of the station!)

We dropped in cold call on this cozy little place with twin smiling, beautiful servers behind the bar. “What can we get ya?” A trendy startup following in the footsteps of time past, for the young chefs and servers at Hige to Boin, fusion is the name of the game!

The izakaya, which is named after a song by Japanese rock band Unicorn, serves the same time told Osakan delights such as karaage, buta-kimchi, eggplant, and shiitake but with their own twist. The Shiitake served here are a perfect 2L size. Keeping the stem intact, one cut is made down the middle of the stem to the back of the cap- but not through it completely. Next, a similar cut is made in the opposite direction like a cross.

These beauties are fried cap side down then cap side up in golden garlic butter, plated, and spritzed lightly with truffle oil, then a dash of truffle powder. Absolutely amazing finish, these. The earthy fragrance and rich taste all the more pronounced for the truffle was one step from heaven! our suggestion is to pair these with a tomato sake, clear, barely pink, and smooth as silk! Ask for the sake with the tomato on the bottle!

Fellow writer for osaka.com, Matt Kaufman had this to say: “Hige to Boin is what I like to call a Reiwa-style restaurant. Although they’ve only been around since 2020, the staff’s creative reinterpretations of traditional izakaya favorites have attracted customers of all ages. They are a great addition to the neighborhood.”

IZAKAYA: Rakuen Tondabayashi らくえん

Address: 5 Chome-6-6 Wakamatsucho, Tondabayashi, Osaka 584-0024. Tel: 09054624846. Open: Every Day 17:00-23:00.

DEEP MINAMI KAWACHI: About a 10-minute walk from Tondabayashi station on the Kintetsu Line, this cozy, narrow restaurant has the definitive feeling of welcome. Possessing a no-frills appeal, and a long counter for sharing suds and shochu, the owner, and friend going on 15 years now, Rikiya Kinoshita smiles happily behind it ready to cook up or pour down anything your heart desires.

“My father-in-law owned a fruit and vegetable shop that sold high quality items for low prices,” says Kinoshita. “I worked there for six years and became familiar with the jumbo-sized shiitake, which are called “Large-sized koshin” shiitake in Japanese. It has been one of the most popular menu items since I opened my restaurant 17 years ago.”

“The way I prepare my style of shiitake is simple” Kinoshita continues. “I grill it on an ensengeki grill and add an original blend of spices including salt and garlic. The recipe is a secret that I can’t reveal, just like Kentucky Fried Chicken (laughs). I can add butter or my original ponzu sauce if the customer requests it. Not to brag, but my ponzu is so good that you can drink it like juice. I have spent the last 17 years perfecting the recipe.”

Called yaki shiitake, grilled over an open hibachi BBQ or ensengeki as Kinoshita-San does these, there are few things more satisfying than a plate of fresh, hot-off-the-grill mushrooms! Frequently toted as ‘steaks of the mushroom world’, these large-sized shiitake beauties are a flavor bomb of umami! If you are on the hunt for large-sized shiitake grilled to perfection, Rakuen is just a short train ride down the tracks to Tondabayashi- and well worth the trip!

Thank you, Kinoshita-San! A simple method with delightful results! We will be there again soon to order a DRINKING GLASS of your custom-made citrus soy ponzu with some of your other signature dishes!

A Few Good Recipes

Welcome to the “Doghouse Kitchen”, home kitchen of the author. We live in the very deepest part of Southern Osaka. We farm two separate parcels of land as well as keep two more in reserve. A ten-minute drive east and we crest the Kongo ridge line into Nara prefecture. We do organic field to table here and what we don’t grow, we source with preferably organically grown vegetables! Here below are a more nontraditional take on shiitake! Enjoy! – Wes Wesson

1.Panko Stuffed Garlic Butter Shiitake (3~4 L sized!)

Author’s recipe inspired by The Book of Tofu and built upon by yours truly!

Meat lovers can pack these with minced beef, chicken, or pork then apply the breadcrumbs. But I prefer this meatless recipe, good for those whom meat is not optional. The earthy tones combined with golden butter and aromatic garlic and parmesan just can’t be beat! Added shredded cheese is optional. I often cook up an oven baked brown rice and firm tofu casserole to go with it!

INGREDIENTS:

· ¼cup unsalted butter, at room temperature

· 3 cloves garlic, minced

· A dash or two of a good sea salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

· 2 L. shiitake mushrooms, stems removed

· 2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley leaves or use dried herbs such as parsley, dill, basil.

· ½cup freshly grated Parmesan

INSTRUCTIONS:

· Preheat oven to 375 F (190 C.) degrees F or toaster oven 220 F. (104.5). Lightly oil a baking sheet or coat with nonstick spray.

· In a small bowl, combine butter and mashed, chopped garlic, season with salt and pepper, to taste.

· Working one at a time, spread butter mixture into each of the Shiitake mushroom cavities.

· In a separate bowl mix parmesan with PANKO breadcrumbs and your choice of dried herbs such as dill, basil.

· Place mushrooms onto the preparing baking sheet, cap-side down. Place into oven and bake for 12-15 minutes, or until the cheese is melted. Serve immediately, garnished with parsley, if desired, or atop a steaming bowl of oven baked tofu in brown rice!

2. Pan Fried Butter- Ponzu Shiitake Sauté

INGREDIENTS:

- – 1Tbs. unsalted butter (ghee, olive oil, avocado oil, optional)

- – 1Tbs. ponzu, or citrus soy sauce.

- – 3~4 L-sized mushrooms or 10~12 small sized mushroom, kept whole, caps and stems intact. Don’t over crowd the pan. Do in small batches.

- – 1 large clove garlic, peeled and thinly sliced

- – 1 tsp. chopped fresh rosemary, thyme, or sage, optional.

- – 1/4 tsp. ground sea salt, or to taste or add a splash of dashi at the very end. Optional: Truffle oil spray, just a spritz!

INSTRUCTIONS:

Step 1: Preheat a 9″ cast iron skillet over medium heat.

Step 2: While the skillet heats prepare your mushrooms and chop your choice of herbs. Dill and parsley are fabulous.

Step 3: Turn the skillet up to medium-high heat and add the butter to the pan.

Step 4: When the butter is mostly melted, add the mushrooms, garlic, and chopped herb of choice, with a few healthy dashes of aji ponzu citrus flavored soy sauce. Toss the ingredients together to combine. Cover. Let the mushrooms sauté for 1-2 minutes before turning.

NOTE: It’s important not to stir all the time, or the mushrooms won’t have a chance to brown, and that caramelized flavor is not to be missed!

Step 5: Cook until the mushrooms are tender with browned edges, about 5-8 minutes turning them no more than 2-3 times total. Season to taste with sea salt, next use a blow torch to brown the top and edges of the cap. Spritz the final result with a wee bit of truffle oil spray, go sparingly, you just want the essence! Give the pan a toss, plate it and enjoy!

3. HUEVOS RANCHEROS (Rancher’s eggs): tuna-egg omelet rolled into tortillas with shiitake.

INGREDIENTS:

- 1 Tbs. unsalted butter.

- 1/4 white or yellow onion, diced.

- 2 small bell peppers or other green peppers.

- 2 medium to large sized shiitake, slightly rinsed and patted dry, slice, stem removed and chopped.

- 2-3 Farm fresh eggs L-size.

- 1/2 tsp. Sugar

- 2-3 Tbs. Whole milk

- 1/2 tsp. Soy sauce or tsuyu (udon dashi-bottled)

- 2 Tbs. chopped fresh dill and parsley leaves or a pinch of dried parsley or basil.

- Dash of sea salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste.

- 1/3 cup (75 ml.) shredded Mozzarella or Monterrey Jack Cheese

- 1/2 cup (125 ml.) Strained Yogurt (with lemon juice, onion soup powder)

- 4~5 Steamed flour tortillas.

- 2~3 fresh sprigs of dill and cilantro, chop finely.

INSTRUCTIONS:

STEP ONE: Prepare the shiitake. If dry, reconstitute in warm water for 15 min. Slice thinly or dice. If using fresh, which I recommend, simply slice to your desired thickness, or chop them into smaller pieces.

STEP TWO: Have made ready in advance: Yogurt with an acid added to coagulate, such as 1~2 Tbs. of fresh squeezed lemon juice. To make this sour cream replacement, I use a full fat yogurt as the low fat will not curdle well. Thickness is the goal and at any rate the end result will be far less calories than regular sour cream. Mix into the yogurt container and set aside for a full fifteen minutes. It should be a lot thicker than it was.

STEP THREE: Fill 4~5 with cheese, fold in half then into a triangle and place them in a tortilla steamer or toaster oven steamer box. Steam these for six minutes.

STEP FOUR: Add 1/2 tsp. of onion powder or a packet (1 Tbs. of onion soup powder) (Lipton’s is great if you can get it where you are) (In Japan, Daiso sells a very tasty three in one package for 100-yen, brown package with and onion on the front) and mix well. At this point you can add fresh chopped dill or any other herb of your choice such as chives, parsley, or cilantro. Pour the contents of the container into a coffee filter lined colander. Place this atop a bowl to catch the liquid run off. Set for 2~6 hours, or even overnight in the refrigerator. The water strained off; you will have a supreme sour cream replacement!

STEP FIVE: Prepare eggs. As these are a ‘rancher’s eggs recipe’, try and go farm fresh! Here in Japan fresh eggs CAN be found in vending machines or at your local Michi no Eki, or roadside rest stop. Break into a bowl, add the milk, soy or tsuyu , sugar and salt- pepper to taste, just a dash or two works fine, whip LIGHTLY. Set aside.

STEP SIX: Have a frypan with the butter melted at the ready. As the butter begins to bubble and slightly brown, add your onions and green pepper. Fry until aroma is released and the onions start to become translucent and smell heavenly. Add strained tuna (optional) and the reserved, chopped shiitake stems. Lightly stir-fry.

STEP SEVEN: Next, spread the vegetables, stems and tuna throughout the pan. In one smooth go add the eggs to the hot pan, turn the heat to low and cover. Don’t pick up that lid for about two minutes to three. After that time has passed, uncover, flip the omelet as one to its other side, cover, cook for 30 sec. longer, shut off the heat and keep the pan covered until serving.

STEP EIGHT: Plate the omelet, add the soft, steamed cheese tortilla triangles on the side, add a dollop or two of your homemade sour cream substitute in the middle of the omelet. Garnish with fresh, chopped dill and coriander leaves and stems. (Chop these very small as you would chives!)

STEP NINE: Using a tortilla steamer, oven toaster steamer container or even wrapped in a paper towel and zapped in the microwave, steam your tortillas for a minute until warm and pliable. Open up and place your desired amount of cheese inside, fold iin half, then into quarters. Steam another minute before removing them to a towel lined basket.

4. “The Dog House’s” Golden Baked Shiitake Pizza

Doghouse style- as long as you get your sauce right, and that best combination of ingredients, throw it all on the pie and bake! Some might argue that too much cheese might kill the taste shiitake attempts to impart to the overall dish. When it comes to oven-baked recipes, I beg to differ; shiitake’s robust woodiness totally compliments toasted, melted cheese.

So long as it’s not a blue cheese or a real sharp cheddar, top that cheese on! Shoot for a white cheese like a mozzarella, or jack, those are the best. Maybe even go four cheeses, but don’t make any of those a blue one. As for the sauce, I like to go for a hearty tomato sauce stewed with a bit of dashi.

In my last article, https://www.osaka.com/businesses/gyomu-super-imported-food-and-super-sizes-at-supersaver-prices/ I proposed some very good frozen pizza pies found at our local Gyomu Super retailers; it wouldn’t be a complete recipe list if I didn’t include topping up a pizza with these wonderful shiitake! So, run! Don’t walk, get yourself one of those premade pies OR try our delicious take on shiitake pizza using a homemade hot milk crust below!

INGREDIENTS

- (8 g) 1 pouch instant (rapid rise) dry yeast

- 2 tsp (10 mL) sugar

- 1 1/4 cup (310 mL) whole milk, warmed to about 38.C. to 45.C.

- 3 tbsp (45 mL) melted butter

- About 3 cups (750 ml) unbleached all-purpose flour

- 1 tsp (5 mL) salt

PREPARATION

In a large, stainless-steel bowl, mix yeast, sugar, warm milk (do not bring this to a high heat or boil, heat slowly until it is warm, and steam is forming then shut off the heat) and melted butter.

Let it rest 10 minutes -allow the yeast to activate. Foam should form along the surface, that’s when you know it’s good to go!

Mix flour with salt. Gradually add to the bowl, mixing with a large whisk, next- a fork, and eventually with your hands once using the fork becomes difficult. Incorporate flour until your dough is consistent and fairly firm.

Flour a work surface and knead the dough, adding a bit of flour now and again until the dough no longer sticks. To knead, fold and flatten the dough for roughly 5 minutes, using the palm of your hand or fist. Twist your palms into the dough ball as you extend your arm pushing the dough into long lengths before folding over and repeating, this creates gluten required for that toothiness we all love in a good pizza dough. For those that are glucose intolerant, massage the dough less, follow your favorite gluten free recipe but in place of the 1.5 C. of water, try the addition of hot milk! It totally makes this pizza, giving it a creaminess that balances the yeast. Soft on the inside, crispy on the outside!

Place the dough ball into a bowl greased with butter, or olive oil, cover, and allow the dough to rise in a warm, draft-free location. (I place my bowl atop my refrigerator. The dough must double in volume. This should take about 45 minutes.

Deflate the dough prior to working it into your chosen pizza shape and thickness.

Top the shaped dough with a light coating of olive oil. Let sit for five minutes. Apply your sauce, dust with parmesan, apply your chosen toppings, saving shiitake and long, thin sliced onions for AFTER you have applied your chosen shredded cheeses. Apply them last, having first mixed them in a small bowl off olive oil, tossed to coat, this allows them to brown and caramelize without burning, seeing as they are the topmost part of the pie. Bake at about 220c. for twenty minutes. Then 250c. for another eight minutes for a nice golden top! Wala! Enjoy!

5. SAKE KUSU JIRU (sake lees/dregs- infused white miso soup) with Shiitake.

PREPARATION OF LEES/DREGS:

Sake kasu is a byproduct when making Japanese sake and therefore there is a wide range in the finished taste of every batch. You can make kasu jiru with kasu paste found in supermarkets, but I recommend using sake kasu made at sake breweries, which produces good Japanese sake in low volume in keeping with aroma. Aroma is key here!

The preparation process depends on the firmness of sake kasu. If it is soft, put it in a bowl with some dashi and smash it up as shown in the picture below.

If you are using hard sheets of sake kasu, soak it in dashi for a while or you can grind it using mortar. Sake kasu can be frozen. If you find good sake lees, you’d better buy extra! Pulverize the lees using a mortar, add to a blender, drop in some hot dashi, blend until a paste has formed. Using a colander and the back of a ladle you can gently stir and fold in the lees into the boiling stock.

This soup is essentially a Tonjiru, or multi winter vegetable soup. Salmon and yellowtail (buri) are recommended for this soup. Sliced or chopped root veggies such as burdock, taro, Japanese daikon radish, turnip, lotus root, and carrot are commonly used. Cut your chosen fish which will be the main ingredient, into large pieces and the rest into bite size pieces. If you have long green onion, slice it thinly for garnish, or chop into many rounds and it will add color to the dish.

BUILDING THE SOUP

Soak the dried kelp and shiitake mushroom in water for several hours or overnight and cut the shiitake mushroom into bite size pieces. Strain the dashi to remove any dust from the shiitake mushroom and put it on low heat.

Bring it to a simmer and add the vegetable that takes long time to cook first.

- Place salmon pieces in a sieve and pour boiling water over them. This removes the fishy smell.

- Put some dashi stock and sake lees in a blender, mix until the sake lees become a smooth paste. Add miso and mix well. (I used a blender to make sake kasu paste, then mixed in the miso using a spatula because my sake kasu paste was not watery enough to use the blender with the miso added to it. You can also use a mortar & pestle or a bowl with a whisk, although it will take a bit longer to make a paste.)

- Cook daikon, carrot, burdock, and konjaku with the remaining dashi stock in a pot until the vegetables are nearly cooked through.

- Add aburaage and salmon to the pot and cook for a few minutes.

- Add the sake lees mixture to the pot and mix gently.

- Scatter the green onions atop, turn the heat off.

Although there are many ingredients involved in this dish, the process of making Kasujiru is quite simple.

A variety of sake kasu recipes exist, many with differing ingredients and preparation can be found on the internet in apps such as Pinterest. With the waning days and countdown toward spring underway, this soup is a heart-warming soup for both the tummy and soul! Give it a try for a weekend dinner on a cold, wet day!

For our star cookers out there, who want to try their hand at the recipes above- or better yet- share one of your very own shiitake recipe- creations, feel free to post those and any feedback in the comments section for this article. Let us know how it goes!

Going to try and make the Sake Kusu Jiru recipe tomorrow.

Excellence! You won’t regret it! And still cold enough these evenings to really enjoy it. You can pick up sake dreggs/ lees at your local supermarket, if so get ones coming from a brewery. A bit eXtra is every bit worth it…but…if you can get to a brewery, or a michino eki, or even a specialty Sake shop, hit those! Salmon, buri, even chicken ( breast) will work!