The English title The Homeless Student sounds like a movie about a university student who has lost it all and is now living on the streets. But that’s not the case here. The original Japanese title is much more straightforward: Homeresu chugakusei translates to Homeless Middle School Student. A young boy suddenly thrown into homelessness without any fault by himself, that’s what the movie is about. A young boy without any street smarts, with no knowledge about soup kitchens and other services rendered to the homeless.

The movie is based on the 2007 book of the same title (Homeless Middle School Student) by Osaka manzai (duo) comedian Hiroshi Tamura.

Born in 1979 and grown up in Suita, a city in the north of Osaka Prefecture best known as the location of the 1970 Osaka World Expo Park, Tamura was the son of a well-to-do middle-class family, along with his elder brother Kenichi and his elder sister Sachiko.

One day, their beloved mother fell ill with cancer and eventually died. Shortly after, their father also had to undergo a lengthy hospital stay, also because of cancer. The father made it out alive but the hospital costs and the loss of his regular job ruined the family financially. Eventually, the family was evicted from their home.

The father never told his children about the problems. So, suddenly, one day, they find themselves locked out of their own apartment.

Kenichi, the elder brother and Sachiko, the elder sister, decide to stay together, to work out things together. After all, Kenichi is a university student and he has a part-time job in a convenience store.

Hiroshi, however, tells them that he has many friends from school, that he has many places where he can stay. He will go solo.

Those friends do exist but Hiroshi has no intention to tell any of them about his situation. He’s too ashamed.

Instead, he seeks refuge in the nearest park. The park is dominated by a large children’s playground slide, vaguely in the shape of a snail shell. A snail shell might have been the image the architect of the sculpture serving as a slide had in mind.

However, painted brown, the sculpture made everyone, not just the children of the neighborhood, rather think of a turd. Thus, the sculpture got the nickname makifun (literally shit roll) and with it came the vernacular name of the park: Makifun Park. Turd Park.

Hiroshi makes the makifun his new home. It’s summer and he can sleep easily on the slide, the structure offers a certain protection.

In his book, Tamura, details his adventures as a homeless, clueless youth as well as his survival strategies quite in detail. Eventually, the parents of one of his friends from school find out about the abysmal situation he lives in…

Table of Contents

Hiroshi Tamura – the Comedian

Having survived his time as a homeless youth in about 1993, Hiroshi Tamura became a successful manzai comedian in Osaka, performing in a duo with Akira Kawashima as his comedic partner.

In their performances as the Kirin manzai duo, however, Tamura began to include more and more references to the “poverty period” in his youth.

A publishing company took notice and urged Tamura to write a book about those experiences.

The result was his 2007 book Homeless Middle School Student. The book became an overnight sensation. It reportedly sold 2 million copies, it was turned into a manga. It was turned into the movie at hand and later into a TV drama. Eventually, Tamura’s elder brother Kenichi got in on the act and wrote a book titled Homeless University Student, telling his version of the events. There was even a parody movie of the book made, Homeless as a Middle School Student (released in October 2008, on the same day as The Homeless Student), which tells the story of middle-aged homeless man forced to return to school to finish his compulsory education.

In short, Hiroshi Tamura’s book caused a sudden but short-lived boom in ‘homeless student’ works. Toho, Japan’s largest film studio, was quick to join in, producing The Homeless Student.

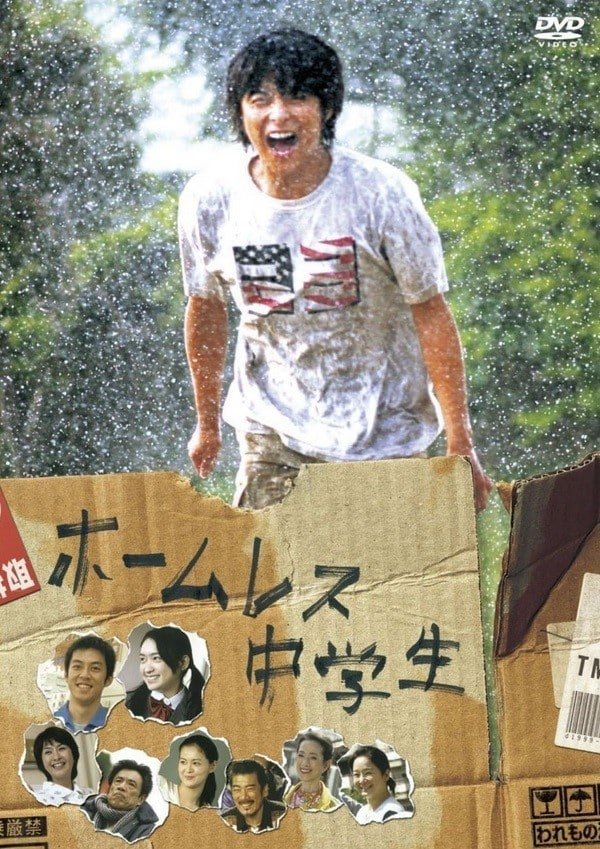

The Homeless Student (Japan 2008) ホームレス中学生

The film starts with the last day at school before summer vacation. Hiroshi, the main character, is leaning at the school gate, enjoying the summer sun rays. Shyly, a pretty girl, a classmate, approaches him. Wouldn’t he want to join her for a night at the movies, she asks him. Somewhat surprised, Hiroshi quickly agrees. Leaning back at the steel gate, Hiroshi is all smiles. He is as happy as any teen in his situation can get.

Just that for the viewer, the scene doesn’t seem to be quite credible. Hiroshi, supposedly 13 years old, is played by Teppei Koike, an Osaka-born actor who was already age 22 at the time of shooting.

Teppei Koike, playing the central character throughout the movie, does a great job though.

Just suspend your disbelieve and accept him in the role he plays. The same goes for his siblings who will soon show up. They are also played by actors visibly above the age of their characters.

Happily looking forward to his summer vacation, Hiroshi returns home. Outside the apartment, he finds all the family’s furniture resting on the street. The apartment door is blocked by yellow tape, marked Keep Out in English and Japanese.

Soon, Hiroshi’s brother Kenichi (Akihiro Nishino) and sister Sachiko (Chizuru Ikewaki) appear, they have no clue what’s going on either. Then the father shows up, played by Issei Ogata. “Sorry, it came to this”, he tells his children, “But now, nothing can be done about it. You are on your own.” Finally, he shouts out “Disperse!” before riding away on his bicycle.

As in the book, Hiroshi decides to take things in his own hands, he heads for Makifun Park.

The Film and the Book

When Tamura wrote the book on his experiences as a homeless youth, he was already a seasoned comedian. He knew how to tell stories and he knew that pain and anxiety can be great material for comedy when told right.

However, his book, while containing a lot of comedic situations, is a book about an absolutely desperate youth who is deeply ashamed of his own situation, unable to seek help and, yes, starving.

The movie does not go as deep into Hiroshi’s feelings and thoughts as the book. It treats things in a much lighter way, clearly aiming for entertainment rather than a portrayal of despair.

In any case, both in the book and in the movie, the few yen in Hiroshi’s pocket quickly run out. He starts a daily routine of searching close to and underneath vending machines for lost coins. Sometimes, he is lucky.

He ponders stealing bread (in the book, not the movie) but he never does. The idea of eating out of the garbage of fast food stores (common among some homeless in Western countries and also done by attitude by some punk rockers) never even crosses his mind.

He would rather ask the old man feeding crumbs to the pigeons in his park for some of the bread – then eating it all by himself. He would try to eat wet cardboard.

Pride is one of his main motivations. Hiroshi wants to duke it out by himself at all cost.

Only in the most urgent cases, when hunger really drives him, he will go and visit his brother Kenichi in his convenience store – where he can always expect a good bento box.

Local children attack Hiroshi, calling him the “turd ghost”. They throw stones at the makifun to get him out. Hiroshi in turn tells them that he is the “god of shit” and if they don’t obey him, they will all get a serious case of diarrhea … oh, wait, you want to see the result of the scene by yourself.

As in the book, Hiroshi finally encounters one of his friends from school and confesses his situation to him. The friend invites him home for dinner. There, he meets his friend’s parents. The father, a gruff man wearing colorful shirts, looks like an ex-rock star. In fact, he was played by rock star / actor Ryudo Uzaki, perhaps best known for his role as failed bank robber in Tattoo Ari.

The friend’s mother, played by Yuko Tanaka, is however very welcoming. She will take care of Hiroshi and his siblings, will try to find them a place to live…

The Director: Tomoyuki Furumaya

The director chosen for the movie, Tomoyuki Furumaya, born in 1968 in Nagano Prefecture, made a name for himself when winning the Grand Prize of the Pia Film Festival in Tokyo (the main festival for up-and-coming directors in Japan) in 1992 with his short film Burning Dodgeball. At the time, Furumaya was still a film student at the Nihon University College of Art in Tokyo.

Furumaya has since shot a large number of films both for the big screen and for TV, usually dealing with youth-related issues. Teenage romantic comedies, school dramas, coming-of-age stories.

This background made him clearly the favorite choice for Toho, the studio producing The Homeless Student.

Osaka Locations

Suita, the city in the north of Osaka Prefecture where the actual story of young Hiroshi Tamura being homeless actually played out, is never mentioned by name in either the book or the movie.

However, Makifun Park is real. It’s Yamadanishi #2 Park in Suita, and yes, the original makifun slide sculpture is still there today. Just that it has been painted blue by now. You can have a peek at the original place in its current condition on the site of local blogger Tanuki.

Hiroshi Tamura went to Middle School in Suita. But not to the school depicted in the movie. Tamura went to Nishiyamada Junior High School. The scenes for the movie showing the school however were filmed at Katayama Junior High School, also in Suita City.

Suita is famous for the 1970 Osaka World Expo Park. The park is not featured in the movie (or book) but the Osaka Monorail, today the most convenient connection to the park for visitors traveling from Osaka or Osaka Itami Airport, is on display a few times.

The Kobe Film Commission invested some money in the movie. Thus, a clearly identifiable beach on the Kobe waterfront makes a short appearance. Some street scenes were also filmed in Kobe, in one of them one can clearly read Kobe Shimbun on a large sign in the background, advertising a local office of the newspaper.

Makifun Park, however, the central location of the movie, was filmed in Omiya Park in the city of Urasoe on the main island of Okinawa, just north of Naha.

Okinawa standing in for Osaka? The fact begs the question, why? Irresistible incentives offered by the Okinawa Film Commission? Reluctance of the Osaka / Kansai authorities to hand out shooting permits involving the makifun or a replica thereof?

In any case, Okinawa it was. Despite its reputation as subtropical paradise, Okinawa does have areas of modern housing (and the small parks that go with them) as bland as any in the outer Osaka suburbs.

Reception of the Film

The Homeless Student premiered in October 2008 on more than 300 Japanese movie screens, earning fourth place on the box office in terms of revenue.

Teppei Koike received the Newcomer of the Year Award at the Japan Film Academy Awards in 2008.

Comedian Hiroshi Tamura however told the story that he was most proud when a real homeless man in central Osaka recognized him on the street and asked him to sign the very cardboard sheet he used to sleep on.