Table of Contents

Introduction

Japan’s film industry has traditionally been centered in Tokyo. Thus Tokyo has all the infrastructure in place to efficiently produce movies: the studios, the directors, the actors, the technicians, all sorts of technical equipment rental places, plenty of agencies for extras of all sorts. Foreign film companies with an interest in shooting in Japan are therefore also immediately drawn to Tokyo. There, the infrastructure seems to be waiting for any project they may want to realize.

However, Osaka has been the setting and / or location for quite a number of films as well, featuring vibrant life in Osaka both in past and present while making good use of the city’s manifold neighborhoods. Neighborhoods that often appear to be somewhat on the rougher side, providing much more convincing backdrops to, say, yakuza movies or films dealing with life in Korean immigrant quarters.

In a loose series, Osaka.com will introduce some of the most remarkable movies shot or set in the city in the upcoming months. Let’s start off this series with the perhaps most famous Osaka movie of all time…

Black Rain (USA, 1989) ブラック・レイン

To say it upfront: the film’s dark yet colorful images of a troubled but exotic Osaka make Black Rain the cult classic it has become. In the film, Osaka looks like a real-life version of the dystopian future Los Angeles depicted in Blade Runner (1982) – and that is certainly no coincidence.

Black Rain director Ridley Scott had previously been the director of Blade Runner. Scott had also directed Alien (1979), sci-fi horror set in quite exquisitely disturbing dark tones. These three films, for all their differences in genre and storylines have clearly in common that they are densely structured visual works – putting the sheer power of the images front and center. The actors do excellent work (most famously Rudger Hauer in Blade Runner and Sigourney Weaver in Alien) and they are given their space to do so while the plots, well, are not exactly always of the freshest sort. It’s genre pictures after all though they often cross over and incorporate elements not typically associated with the genre in question.

Back to Black Rain. The movie’s title appears in black top-down writing over a red circle resembling a rising sun, or, for that matter, the circle in the center of the hinomaru, the Japanese flag, making clear where the plot is headed.

The Unisphere, a giant statue of the globe left over from the 1964 New York World Fair in Flushing-Meadow – Corona Park in Queens, New York City appears, glowing in the rays of the morning sun. Biker in a black leather jacket races towards the statue, towards the world it represents, so to say.

The biker, Nick Conklin, we learn, is a detective with the New York Police Department (NYPD), we soon learn. Played by Michael Douglas, the detective comes off as the typical New York cop a portrayed in productions of the 1970s and ‘80s: strongly opinionated and thus always in trouble with his superiors, not always holding up the law himself when he deems the situation calls for it, loudmouthed and cursing, and, well, considering himself working in a big gray area where one hand greases the other. In short, the movie detective cop of the period is generally a corrupt and violent renegade and, in the case of Nick Conklin at hand, quite reckless. The latter trait is made clear when Nick’s character is introduced, showing him engaging in a wild motorcycle race on a whim on a public walkway along the East River. A beautifully filmed motorcycle race, one might add. Still, it’s made clear from the beginning that Nick is deep down a good guy.

Movie detectives always have their sidekicks. Nick’s partner is young and flashy Charlie Vincent (Andy Garcia), a honest though somewhat naïve young cop who loves expensive suits, exquisite shoe and the joys of life in general.

While the two are out for lunch at an Italian restaurant, Nick zooms in on a peculiar group sitting around a table. This is a meeting between Italian-American mobsters and Japanese gangsters, he quickly concludes.

Suddenly, another, quite menacing Japanese gangster makes his big entrance, robbing a box from the apparent chief of the Japanese at the table, then killing him and his bodyguard.

A wild chase through a meat market ensues. Nick eventually captures the culprit, a man named Koji Sato (Yusaku Matsuda) from Osaka.

Forces on a higher political plane intervene and arrange Sato’s immediate transfer to Japan. Glad to get rid of Nick for a time (while a corruption investigation against him is underway), Nick’s superiors order him and his partner Charlie to guard Sato on the trip.

Osaka is introduced by an aerial sunrise shot of the city and the Yodogawa River, a city shrouded in smog and dominated by smoke-belching chimneys.

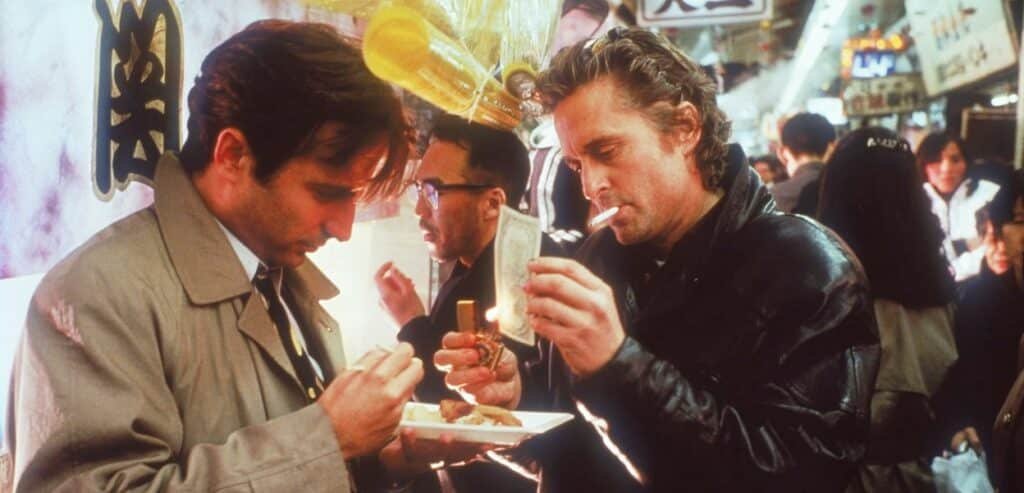

Speaking of smoke and steam… smoke or steam is present in almost every shot of the movie, both in the New York and Osaka scenes. Leaking steam pipes, steaming market stalls and soup kitchens, heavy cigarette smoke in almost every indoor sequence. All that smoke and steam adds a lot to the atmosphere conveyed: mysterious, dynamic and highly visual.

Why Osaka?

Why did director Ridley Scott choose Osaka as location for the film? The late 1980s were the time of Japan’s ‘bubble economy’. Japan had the world’s second-strongest economy, Japan was felt as a danger to the whole of the American industry. All eyes were on Japan. With that came a strong fascination of all things Japanese – ‘Japan, that’s the future’ was the prevailing view, in the U.S. at least.

For Alien and Blade Runner, Ridley Scott had to create a future by himself while Japan presented all the mysteries, dangers and adventures of the future right there in the present.

The original plan was to shoot Black Rain in Tokyo with Kabukicho, the brightly lit but inscrutable entertainment district of Shinjuku taking center stage. The Tokyo bureaucrats were however not forthcoming with shooting permits. Every tiny step had to be debated over and over again.

At the same time, officials from Osaka approached Ridley Scott and his producers, offering them almost unlimited access to locations and great assistance would move to their city. The lights of Dotonbori could easily stand in for the lights of Kabukicho.

Ridley Scott picked up on the offer.

Osaka Yakuza Crime Tale and the Japanese Actors

Upon landing and still on the plane, Nick and Charlie hand over Sato to the Osaka police. So, they think. Turns out, though, that they have been fooled by Sato’s associates.

Embarrassed beyond belief, Nick and Charlie decide to stay on in Osaka, determined to help in the recapture of Sato. They receive the permission to follow the development of case as unarmed observers. Assistant Inspector Masahiro ‘Masa’ Matsumoto (Ken Takakura) is set aside to be their handler.

There would be no point in further following up on the story here. That would just take the thrills away from watching the film yourself.

Let’s just say that having veteran yazuka movie actor Ken Takakura closely interact with the two American was a great choice Ridley Scott made. Always calm, always subdued, by turns disgusted, by turns fascinated by the behavior of the two American detectives, especially Nick, Takakura delivers a truly outstanding performance.

The other true hero of the film is Yusaku Matsuda, playing Sato, the somewhat juvenile villain who seems to actually relish his murderous depravity. ‘American culture made him that way, poisoned him.’, a senior yakuza remarks in one central scene.

Yusaku Matsuda, the actor, already suffered from bladder cancer when filming started. He decided to forgo treatment as chemotherapy would invariably have changed his appearance. Matsuda did not inform Ridley Scott of his illness. He died a few weeks after the premiere. Ridley Scott then dedicated to film to him.

Osaka Locations

Nick and Charlie stay at a Dotonbori hotel from where they can overlook Ebisu Bridge with all those colorful neon light images covering the building fronts. What they see is the real old Ebisu Bridge, long before the bridge was secured with fenced-off side areas to prevent overly excited fans of the Hanshin Tiger baseball team to jump into the Dotonbori Canal.

They walk the long, roofed Dotonbori shopping street and are threatened there by a gang of young bosozoku outlaw bikers. It’s quite a fascinating scene… the deserted shopping street at night, lit up with store signs in Japanese, lots of bicycles parked in the center of the street, when suddenly the biker posse circles around them, seemingly just playing a mysterious, foolish game. They are actually members of Sato’s gang, we later learn.

In fact, though the street is clearly meant to be Dotonbori – Osaka police didn’t grant permission to shoot at the actual location. A street in Juso had to be dressed up as Dotonbori for the shoot.

Osaka Castle comes into clear view when Nick and Charlie are taken along to the police raid of a sento bath, a suspected hideout of Sato.

The sento bath is located in a very crowded old Osaka shopping street, ending abruptly at an elevated train track. A street image that clearly aims at portraying Japan / Osaka as very different from America.

Instead of taking the rides offered by Osaka police, Nick and Charlie tend to insist on long walks home at night. Given that their hotel is right at Ebisu Bridge in Namba in the south of Osaka, walking there from Umeda in the north of the city, makes for a very long walk indeed.

So, we see the two walk through the deserted, cathedral-like shopping mall on the ground floor of Hankyu Umeda train station. A lone biker seems to be set for a game with them, pranking Charlie by taking his coat, Naively, Charlie follows the biker… a fatal decision leading to one of the most violent scenes of the movie.

Mourning the loss of his partner Charlie, Nick wanders on to the old Shinsaibashi Bridge. The bridge was still in full function when the film was shot, it was dismantled in 1995.

Nick eventually concludes that gangster moll Miyuki (Miyuki Ono) might lead them inadvertently to Sato. He and Masa (Ken Takakura) stake out her home, situated in an apartment building right next to the fish section of the Osaka Municipal Central Wholesale Market. While waiting for her to appear from the building Nick and Masa have a deep talk about the cultural differences between police attitudes in the U.S. and Japan.

Miyuki eventually appears from the building, the detectives follow her to the Nippon Steel Works in Sakai City, south Osaka.

The steel foundry makes for an excellent movie location with its sparkling flows of orange-red molten steel, with its multitudes of workers and trucks. Indeed, a yakuza meeting takes there and Sato is present. He eludes one more time.

Napa Valley, California

Throughout the Osaka part of the movie, the different cultural backgrounds of the New York and the Osaka are a constant topic. The two sides frequently clash but, mostly thanks to Masa, things can always be solved or at least smoothed over.

Similar cultural frictions took apparently place between Ridley Scott / his Hollywood producers and film crew on one side and the Osaka authorities in charge of handing out shooting permits on the other. Frictions that could not be solved.

Rather abruptly, Scott called off all shooting in Japan and returned to the U.S., citing “too much red tape” as the reason. That’s why the final motorcycle chase, Nick hunting Sato, had to be shot in the vineyards of Napa Valleym Northern California rather than in the countryside outside of Osaka.

The set designers did however a great job in making the Napa Valley farm look like Japan. The same goes for a few other locations (i.e. the underground parking lot below Hankyu Umeda Station where Charlie meets his fate).

The Black Rain

Black Rain hit the nerve of the time and became an immediate success both in the U.S. and in Japan. It has since become a cult classic, along with Ridley Scott’s Alien and Blade Runner.

But why was the film titled Black Rain? At one point in the movie, a senior yakuza leader tells Nick about his having survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the subsequent nuclear fall-out, manifesting itself in the form of black rain. The event turning him into the man he has become. No other reference to the war or the nuclear bombings is ever made in the movie.

Coincidentally, in the same year 1989, Japanese director Shohei Imamura released a film with the same title (Kuroi Ame, translating to Black Rain) which deals with the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing in detail.