Table of Contents

Kamagasaki

For decades, the Osaka homeless / day laborer area formerly known as Kamagasaki and more recently as Airin has been considered as the perhaps grittiest urban area in the country. Located close to the Shinsekai entertainment district with its iconic Tsutenkaku Tower, Kamagasaki was home to several thousand homeless people, many of them sleeping on flattened cardboard boxes right out on the streets.

The area had an infrastructure geared specifically towards the homeless population: the Airin Labor Welfare Center offered job placement counseling, it served as a daytime shelter, it featured a clinic and allowed the homeless to officially register by using its address. The latter was crucial for people drawing pensions or other government benefits – they needed a fixed address and the Labor Welfare Center provided it.

Kan Mikami and Yuka Yokoi at Kanmuriya, a dive bar in Nishinari

Across Kamagasaki, soup kitchens provided food, vending machines sold shoju around the clock, often in semi-enclosed spaces which doubled as cheap self-service bars.

In the morning, construction company vans pulled by and selected the day laborers they needed from the healthier folks of the homeless crowd.

For those with some form of a slim income, cheap nightly or weekly rentals were available. Coin-lockers were for rent on a monthly basis for the homeless to stash their valuables.

As ghastly as parts of the area and some of its inhabitants looked, the area did provide a home for people who couldn’t survive anyplace else. Even more than that, it provided a community. Desperate people from all over the country flocked to Kamagasaki because they knew that despite all the squalor, they would find a sort of society of likeminded folks there.

One of the rules of the Kamagasaki area was: No Photos! Many of the folks living there had run away from something or other elsewhere or they simply didn’t want to be exploited as down-on-their-luck photo subjects.

Roger Walch

Read the Osaka.com interview with Roger Walch here:

This rule did not apply to Roger Walch, though. The Swiss, living in the Kansai region since 1998, regularly visited the Kamagasaki area and soon became friends with many of its inhabitants. He became the rare figure who could walk the streets of the neighborhood with a running video camera on his shoulder without anybody giving it a second thought.

Walch, a film maker, writer and music composer fluent in Japanese, specializes in a film genre one could call poetic documentary. He shot a film on Gunkanjima, the ruin island off Nagasaki when the island was still closed off (he paid an old fisherman to get him there secretly), he documented the tsunami devastation in Tohoku right after the March 11, 2011 earthquake.

One day, Japanese folksinger Kan Mikami approached Walch with a rather strange request: Mikami, who speaks not a word of German, wanted to star in a German-language movie. Because he thought that German sounded cool.

The resulting film was shot in Kamagasaki in 2017, at a time when the neighborhood still functioned as it had for many years. Only months after the shooting, demolition teams moved in to tear down many of the existing structures. A lot of the homeless were pushed out in favor of newly constructed hotels serving visitors to the Shinsekai entertainment district as well as international visitors to Osaka on a shoestring budget.

Walch’s film serves thus a sort of final document on the vitality of the area when it provided a home to the homeless. At the time of the shooting, everyone involved was well aware of the fact that the traditional ways of the neighborhood were coming to an end soon.

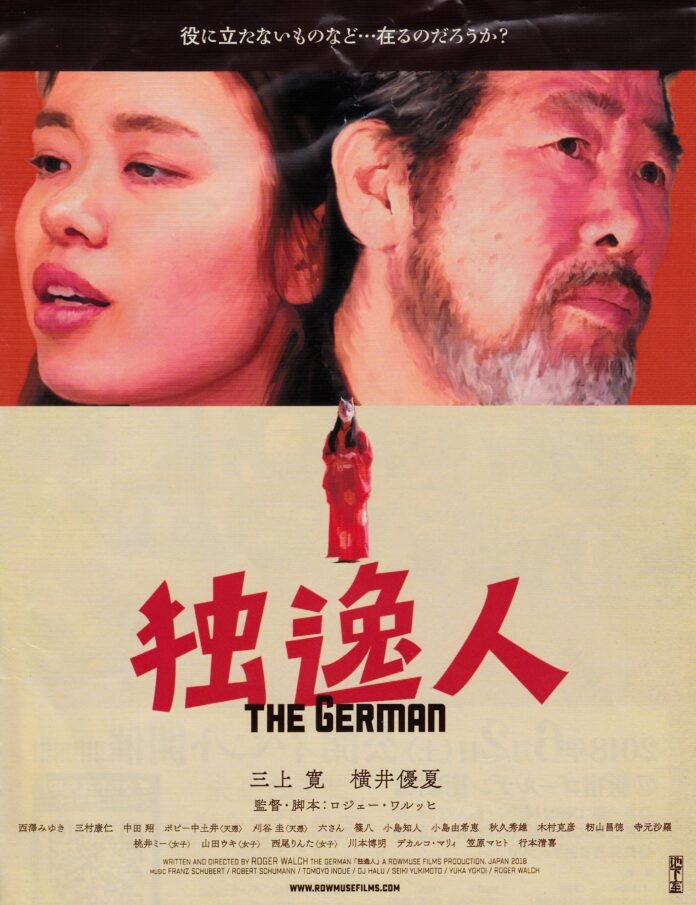

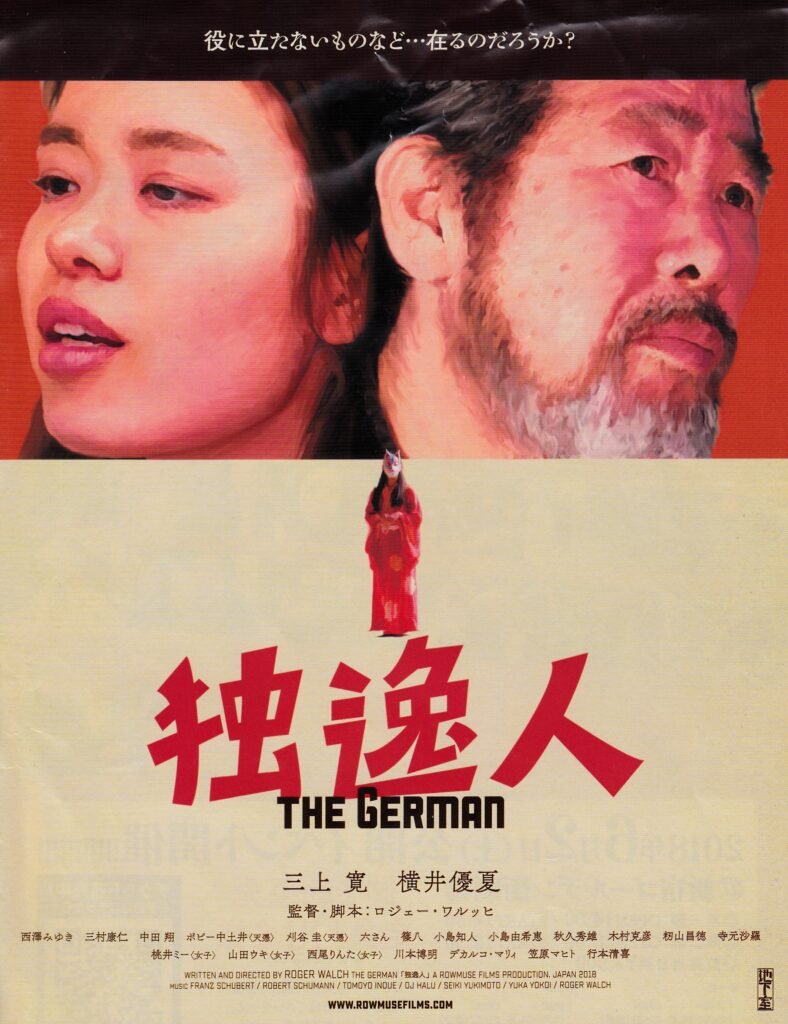

Der Deutsche / The German

Kan Mikami plays an older Kamagasaki resident, living in a tent made of blue tarp. He had been a professor of German philosophy but after he lost his family in a tragic accident, he renounced the world and moved in with the homeless. He also refuses to speak Japanese and talks only in German. Not in the casual German spoken in today’s Germany though but in the heavy-duty German one finds in the texts of classical philosophers.

The homeless around Mikami seem to fully accept his quirks and he has no difficulties communicating with them. They simply call him doitsujin (the German).

One day, Mikami witnesses a black yakuza van stopping. A blindfolded girl with her arms bound on her back is ceremonially thrown out of the bus and been left on the street when the van speeds away.

Mikami takes care of the girl (played by opera singer Yuka Yokoi). In other words, he takes her onto a grand tour of all of Kamagasaki. To the dive bars, to the shopping malls frozen in time since the 1970s, into the ghastly hallways of the Airin Labor Welfare Center, to the most traditional oden food stalls, to Triangle Park. Many real homeless / inhabitants of the area play small roles as people encountered on the way.

The girl follows simply follows Mikami. She never speaks in the film but she seems to understand Mikami’s German-language ramblings, responding to him by singing German-language Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann lieder. She never misses a beat. Her sad songs fit each occasion perfectly. Soon, a deeper relationship develops between Mikami and Yokoi.

If that sounds like a strange mix of high-concept art with the gritty streets of Kamagasaki, then, yes, that’s what it is.

The yakuza group leaves the girl (Yuka Yomoi) on the streets of Kamagasaki

Butoh dancer in the streets of Kamagasaki

But the mix works. Mikami comes off as a worldly though somewhat peculiar guide who knows all the secrets and all the details of the neighborhood. Yokoi radiates a certain outer-worldly presence and greatly helps in mystifying the scenery.

In the course of the tour by the two characters, Kamagasaki turns into a magical place. Street artists pop up everywhere. A powerful trio of dancing girls, a butoh dancer on a street intersection, a lonely jazz trumpet player late at night in the deserted streets of a run-down shopping mall with all the shutters down.

Roger Walch himself said that the film is his declaration of love to Osaka and to Kamagasaki in particular. He succeeded. The film truly breathes the beauty of Osaka’s wildest edges.

Roger Walch on Vimeo here

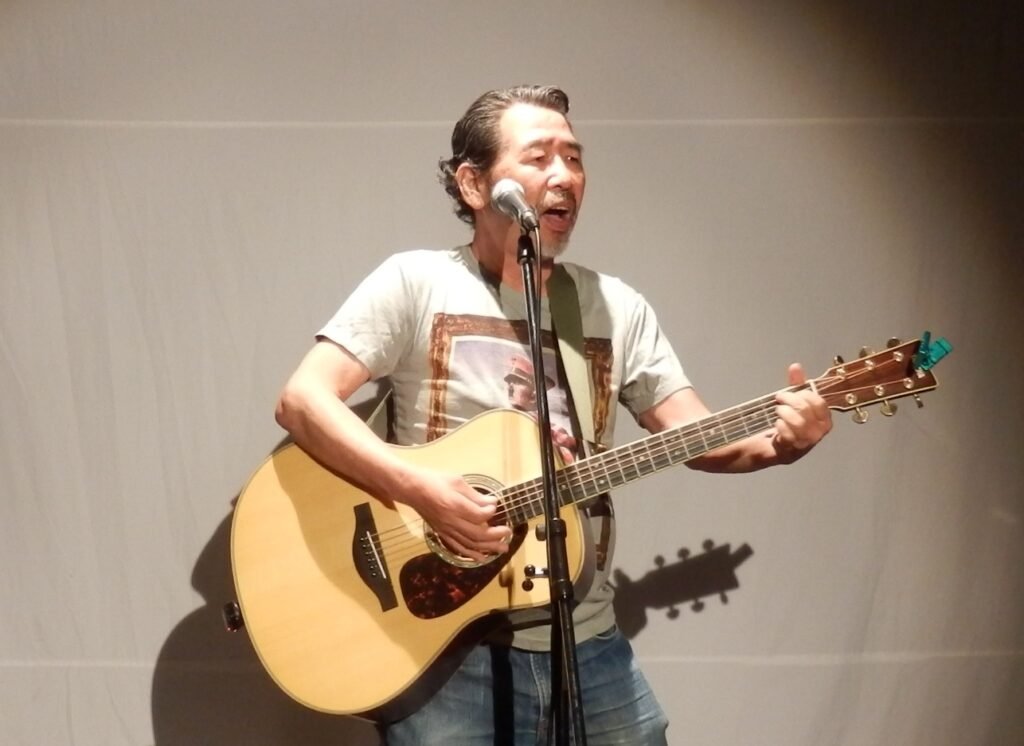

Kan Mikami in concert after the Tokyo premiere of Der Deutsche (The German). Photo: Johannes Schonherr