Table of Contents

An Annual Midsummer Event

Art Osaka 2024 just ended today. So why am I here telling you this? Because Japan’s longest-running contemporary art fair will be happening again next summer, so mark your calendar for Art Osaka 2025! The event, which lasts for several days every summer, is a chance to see an incredible variety of new art you won’t find at museums, art that for the rest of the year is scattered across galleries around Osaka, Kyoto, Tokyo, elsewhere in Japan, and overseas.

Osaka City Public Hall

Osaka City Central Public Hall, that magnificent red-brick edifice in Nakanoshima (completed 1918), is even more gorgeously ornate on the inside. In one of those pandemic silver linings, it became the main venue for Art Osaka when the previous site, a hotel in Umeda, was deemed too confined. The contrast between rows of white-cube booths lined with contemporary art and soaring Neo-Renaissance décor above them is delightful (the director of an Aichi-based gallery told me she chooses what to exhibit with this contrast in mind).

Creative Center

Meanwhile, at Creative Center Osaka on the industrial waterfront out in Suminoe Ward, Art Osaka’s new (as of 2022) Expanded section takes advantage of the vast scale of the former Namura Shipbuilding yard to show larger artworks. According to Tomoko Koizumi of the Art Osaka public relations team, this not only enables visitors to immerse themselves in large-scale works and interactive experiences, but also gives artists exposure to potential buyers from museums and private collections.

Herein lies the difference between an art fair and its easily confusable cousin, the art festival. Art festivals tend to be organized by or in partnership with regional governments, to sprawl across many venues, to go on for months, and notably, to show but not to sell art. Aiming to attract visitors from other areas, art festivals in Japan are closely connected with “regional revitalization,” an urgent issue for every part of the country except Tokyo. The world’s premier art festival, the Venice Biennale, is the Olympics of art, with artists selected to represent their nations and prizes awarded. By contrast, an art fair is like a city marathon open to anyone willing and qualified. At Art Osaka, the results were fascinating this year as always.

Attending the Preview

At a July 19 preview at Osaka City Central Public Hall, 45 gallerists and a number of artists were on hand, talking to visitors and the press. Works by some big names (Yayoi Kusama being the most internationally known) were on view, but the focus is on young and mid-career artists. With each gallery aiming to show an array of works in a booth of limited size, the pieces tend to be smaller, and there is more work in traditional media (painting, sculpture, printmaking etc.) than there is of the video, installation, and mixed media that often predominate at art festivals. Besides these tendencies, it would be hard to point to a prevailing trend. Abstract, figurative, hand-crafted, mechanically processed, cuddly, provocative, approachable, cryptic, serious, humorous––it was all there, evidence that we are in a post-“ism” era when no movement or medium dominates.

Microcosm of the Japanese Art Scene

Video artist Masayuki Kawai told me, “I’m based in Tokyo, but there it’s a bit more international, whereas Art Osaka really gives you the domestic gallery scene in miniature. Each year I can get a sense of what’s going on in the Japanese art world all in one place.” Eight galleries at the main venue were based in Korea or Taiwan, the rest divided among Osaka, Tokyo, Kyoto, and a few other locations. The convivial atmosphere was the opposite of a hushed museum visit.

In an unlikely collaboration between Art Osaka, Mos Burger, and Hiroshi Fuji, an artist who works with recycled toys, a workshop was offered where participants could assemble their own creations from a rainbow array of plastic toy parts. This playful event seemed to exemplify the open-mindedness of Art Osaka, and indeed of this city we know and love.

Expanded Section

The addition, two years ago, of the Expanded section has been a game-changer for Art Osaka. There is a shuttle bus from Nakanoshima out to the site in Suminoe Ward. If visiting the area separately, it’s near Kitakagaya Station on the Yotsubashi line. The main building at Creative Center Osaka (CCO) is a hangar-like industrial space suitable for art too large to fit in a gallery, as well as interactive and sound-producing works.

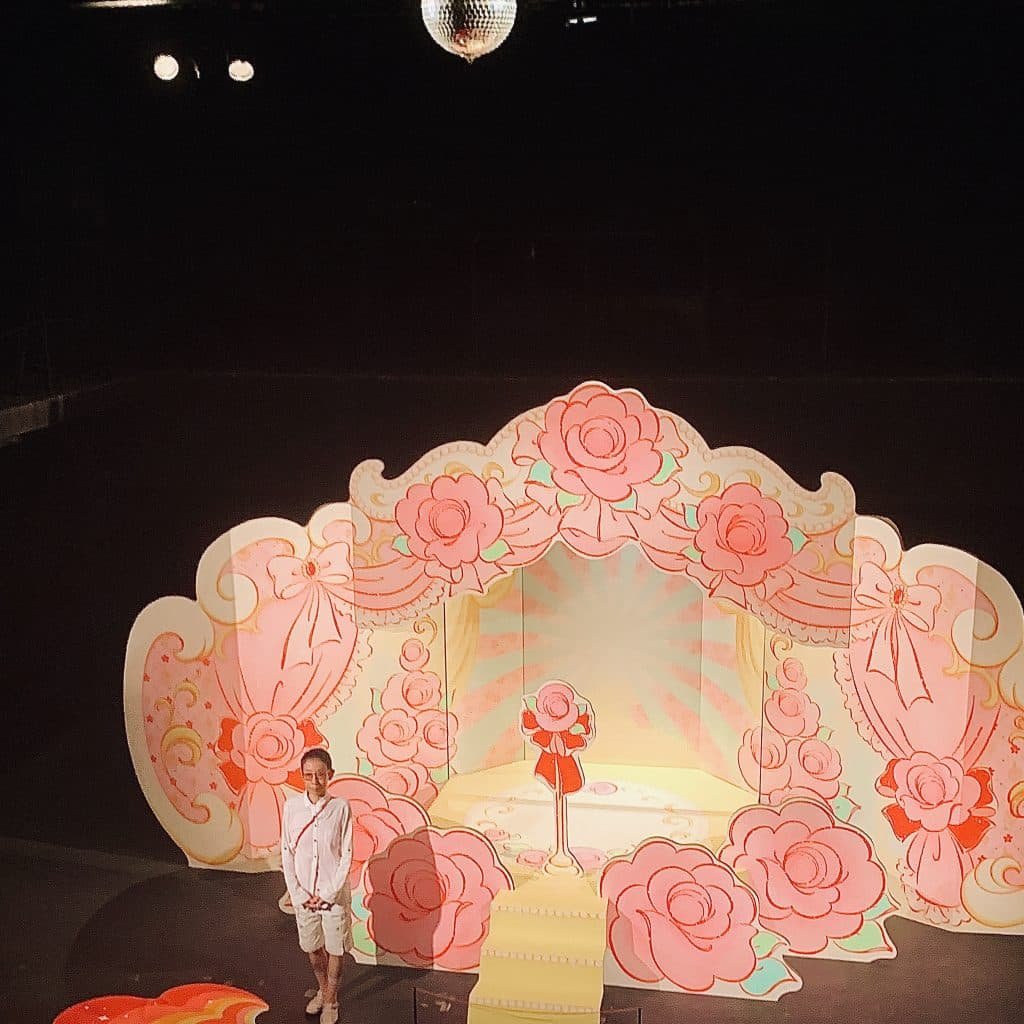

On the second floor, Minako Nishiyama presented ♡Cinderella’s Dream Stage♡, (1996), a life-sized blow-up of a theatrical stage from the Licca-chan toy series (Licca-chan, the “Japanese Barbie,” is a blonde but racially ambiguous fashion doll). Nishiyama modeled it on a paper-doll style assemble-it-yourself cardboard cutout, and you can walk around the back of the piece to see the humdrum workings behind the glittery pink femininity of the “dream stage.”

Koichi Mori and Takehisa Mashimo

On the same floor, breathing garden, a participatory work by the duo of Koichi Mori and Takehisa Mashimo, incorporated light, sound, and plants in columns resembling giant test tubes. The plants’ carbon dioxide levels triggered changes in the venue’s light and sound as they underwent photosynthesis. Visitors could participate, breathing out to brighten and in to darken the lights, in a biofeedback loop that was extremely meditative after a few inhalations and exhalations. The work was presented by The Third Gallery Aya, whose director Tomoka Aya says of the Expanded section, “It’s a truly intriguing contrast with the main space. One is beautiful and historic, the other grungy and post-industrial.”

Hal Osawa and Kozo Nishino

Elsewhere at Expanded, the youngest exhibiting artist, Hal Osawa, showed Discharge, a group of large and stunning calligraphic paintings inspired by Japanese onomatopoeia such as pota-pota (dripping) and zaku-zaku (crispy or crunchy), made by applying ink to a copy machine, blowing the images up to huge sizes, then restoring the digital data to analog form by painting over it in acrylic on silver panels. The enormous column-free space on the top floor of the main building was dedicated to Kozo Nishino’s Stratosphere, a group of massive but feather-light titanium sculptures, monumental in scale yet entirely hand-welded.

Mikiya Matsuda

Meanwhile, the third floor was a thrilling free-for-all of sculpture and installation. When I visited, Mikiya Matsuda was at the site meticulously laying out a floor-based work consisting of US pennies varying in age and coloration, part of his installation Less is More. He told me, “It takes most of a day to line them up. I don’t get into a meditative trance or anything, it’s just work. I call myself an ‘art worker’ rather than an artist. Once they’re lined up, I’ll sweep them away and do the same tomorrow with one-yen coins, then back to pennies the next day.”

Kagoo

In addition to the 16 galleries at CCO, another five were situated at Kagoo, a former furniture warehouse. It’s one of more than 50 venues in the area which Chishima Real Estate, owner of a third of the land in Kitakagaya, has already made part of its 20-year (thus far) master plan to transform this decrepit industrial zone into a waterfront arts and culture mecca. These include former shipbuilding warehouse Super Studio Kitakagaya, where artists can rent studios, and former ironworks Smasell, a newly opened “sustainable commune” with everything from art to clothing, interior goods, and craft beer. Art Osaka is a once-a-year event, but the scene in Kitakagaya is expanding year-round.

At all the Art Osaka venues, price lists were displayed or available on request, and anyone thinking of getting into collecting would do well to start here. The top-priced work by an esteemed artist, recently deceased after a career of many decades, was going for the equivalent of $13,330, and works by emerging artists were selling for hundreds. This reflects not the quality of the work, but the lack of a major commercial art market or widespread culture of art collecting in Japan.

Art Osaka 2025: Things to Come

Even Tokyo, let alone Osaka or Kyoto, has nothing like the gallery-hopping districts of New York or London. While there’s no shortage of rental galleries where anyone can exhibit for a fee, commercial galleries – which represent artists, and are driven to seek out and cultivate talent because their business model depends on selling the work – are relatively scarce. Meanwhile, Japan’s major museums are mostly public, taxpayer-funded institutions, with all the stodginess that implies. There are actually quite a few commercial galleries around Osaka and elsewhere in Kansai, but they aren’t clustered in a particular neighborhood and many have irregular schedules, which makes this art fair all the more crucial for emerging and mid-career artists, galleries, collectors, and anyone interested in new art. If that’s you, then be sure to catch Art Osaka in 2025.