As a country with a strong sense of tradition, Japan has a great many festivals throughout the year. Some, like Kyoto’s Gion Matsuri, Tokushima’s Awa Odori and Osaka’s Kishiwada Danjiri Matsuri are world famous and attended by thousands of people. While these huge festivals obviously make for quite the spectacle, it can be difficult to get close to action and almost impossible to take part.

In my experience though, arguably the most interesting festivals, take place at a much more local level. Attended by just a few dozen to a few hundred people, they offer a much more intimate experience; a chance to interact with local people and sometimes even the opportunity to join in.

The downside however is that it can be very difficult to find information on small local festivals and even harder to fit them into an itinerary. And while many of these festivals are being revived after the Covid hiatus, sadly not all of them are and some are at risk of being lost forever.

Table of Contents

Kongo-san Renge

One particular festival which thankfully did restart last year is the Renge Grand Festival at Tenporin-ji Temple, near the summit of Mount Kongo on the Osaka/Nara border. This unusual Shugendo (ascetic mountain religion) festival attracts not just Yamabushi (Shugendo practitioners) but also many people from the villages near to Mount Kongo.

Taking place each year on July 7th, the anniversary of the death of the founder of Shugendo, En-no-Gyoja, this festival is the oldest and most important festival that takes place on the mountain. The name Renge translates as Lotus Festival as the lotus is an extremely important flower according to Buddhism. It signifies purity and the ritual offering of lotus flowers is a key aspect of the festival.

And in Shugendo, mountains are considered as gods and so by practicing in the pure, clean air, Yamabushi hope themselves to become pure and clean. In fact, it was in these mountains that En-no-Gyoja first began to develop the concept that would go on to become Shugendo.

Climbing the Mountain

With the festival beginning at noon, the first step is hiking the 1,125m mountain. Mount Kongo is easily accessible by bus from either Kawachinagano Station on the Nankai Koya Line or Tondabayashi Station on the Kintetsu Minami-Osaka Line with the final two bus stops both being close to trailheads.

My preferred route is to take the bus all the way to the final stop, Kongo-san Ropeway-mae and climbing the mountain from there. This route, while quite steep in places, is well sign-posted and not especially difficult, taking around 2 hours to reach Tenporin-ji, close to the top of the mountain. The alternate route, starting near the Kongo-san Guchi bus stop is shorter and can be done in 60 to 90 minutes depending on your pace but involves mostly climbing one long staircase.

Processions and Prayers

The first thing you would notice once you reach the temple is the large gathering of people dressed all in white and holding large conch shells. These are the Yamabushi mountain ascetics in their traditional Shiroshozoku robes. The conch shells are called Horagai, special horns that the Yamabushi play not just before they offer prayers but also to ward off potentially dangerous animals as they wander the mountains.

As noon approaches, the assembled Yamabushi form two long lines. Then in unison, those in the procession beat three hollow thuds on their Horagai and blow them in unison as the procession begins to march forward.

They walk slowly up out of the courtyard, underneath an old, wooden torii. Torii gates, normally associated with Shinto Shrines, are an unusual sight at Buddhist temples. But this place keeps the concept of Shimbūtsu shūgō, the close, syncretic union of Shinto and Buddhism very much alive. In fact, this intimate association between the two religions, as well as many folk traditions, is an integral part of the practice of Shugendo.

The procession makes its way slowly up the path, blasting their horagai horns as they go, until they reach the first port of call; Katsuragi jinja. This small Shinto shrine sits at one of the highest points on Mount Kongo. It is dedicated to Hitokotonushi-no-Okami, the god of one word, to whom En-no-Gyoja prayed to when he was training on this mountain at the age of 16.

Once everyone has gathered before the main hall of Katsuragi jinja, the Yamabushi and many of the villagers begin to chant several mantras in a hypnotic tone. Each mantra is dedicated to a specific deity, often gods of specific mountains within the surrounding range. One of the Yamabushi ends each mantra by shaking his Shakujo, a walking staff adorned with metal rings, before beginning the next.

With the prayers at Katsuragi jinja complete, the procession moves on once again, back towards the courtyard in front of Tenporin-ji. Here they stop in front of the Gyoja-do, a small hall which enshrines En-no-Gyoja to offer more Prayers. Finally, the procession moves on up the rough, stone steps to Tenporin-ji itself. This time, only really the Yamabushi take part in the prayers as the majority of the spectators stay in the courtyard to find the best spot to watch the next stage of the festival.

Shugendo Fire Ritual

Near the center of the courtyard is a small but imposing statue. A weather worn figure of a man with a piercing gaze and dressed in loose robes. In his right hand he holds a sword and in his left, a whip and behind him, an aura of bright orange fire. This is O-Fudo-Myo-o-sama, an important Buddhist deity and a principle protector of Yamabushi.

In front of the statue is a large table containing numerous offerings such as fruit and sake. And in front of the table is a large pile of branches, about the height of a man, covering a stack of logs cut from cedar trees.

Eventually the Yamabushi descend from the temple and assemble in the courtyard, either side of the pyre. One of the group approaches the abbots of Tenporin-ji and Sanbo-in and bows. Then he moves to the table of offerings in front of the statue, bows again and retrieves a scroll from a lacquered box. Finally, and with very precise movements, he circles to the opposite side of the pyre to read the speech contained within.

Once he has finished the speech, he carefully returns it to the lacquer box before another Yamabushi approaches the table. After bowing to the statue, he picks up a longbow and a handful of arrows before slowly walking around the pyre and stopping at each side.

Each time he stops, he plants his feet firmly on the ground, nocks an arrow and raises the bow. He then makes a short declaration and, as he speaks the final syllable, launches the arrow high into the air. Once he has fired arrows to the north, south, east and west of the pyre, he nocks one final arrow and fires it straight into the pyre.

A pair of monks are next to approach the table. They each pick up a large bamboo trunk, split at one end and filled with kindling. The kindling is lit and the two monks present the now burning bamboo to the statue of O-Fudo-Myo-o before walking to the opposite side of the pyre. Here, they gently rotate the bamboo poles and knock them together, almost as if they were clashing spears. Finally, they thrust them into the base of the pyre, one either side.

It doesn’t take long for the pyre to begin to smolder. As it does so, the abbot of Sanbo-in (part of Daigo-ji temple in Kyoto) makes his way to the front of the pyre and takes a seat on a bearskin mat and prepares himself for his part of the ritual, while the gathered Yamabushi play their horagai.

With their refrain finished, a brass bell is struck twice and a senior monk begins to chant. The rest of the Yamabushi join the chant in quick succession, joined this time with the rhythmic beating of a taiko drum.

This part of the ritual is relatively simple and includes throwing sticks, which represent human desires, towards the fire. As the ritual and prayer continues, the sticks are gathered up and thrown onto the pyre to represent the burning away of human suffering. Goma fire rituals such as this are an integral part of Shugendo and are performed at many temples across Japan that have a Shugendo connection.

While this takes place, the fire at the heart of the pyre gathers strength and a thick, grey smoke begins to billow upwards, spinning like a tornado. As the wind shifts, the smoke drifts over the gathered spectators and can sometimes get so dense that you can barely make out the other side of the courtyard.

Once his part in the ritual is finished, he returns to his seat and Katsuragi Koryo-san, the abbot of Tenporin-ji temple, makes his way to the bearskin rug, again accompanied by the cacophony of conch shells.

His part of the ritual is slightly more complicated. While the Yamabushi chant to the beat of the drum, the abbot takes a stick (or sometimes a small sword) and strikes a small block to his left several times before making slashing movements towards the pyre. He then places the stick back on the block before drawing and opening his fan to perform a few gestures.

By now the smoke is dissipating and the heat of the fire intensifies to the extent that you can feel it strongly on your face even from 10 or 15 meters away. Hotter even than a typical Japanese summer day. The abbot then takes up a second stick, this time on his right side, which he uses to strike another block and then point at the fire rather than slash at it. Finally, he holds his long string of Juzu Beads towards the fire and runs them through his hands making sure to grasp each one.

Walking on Fire

As the ritual comes to an end and the blaze on the pyre dies down, the Yamabushi begin to dismantle it, using hooks to pull the logs down onto the ground. The still burning logs are then arranged to form a bridge leading towards the statue of O-Fudo-Myo-o. At the far end of the bridge, in front of the statue, soft evergreen branches are placed on the ground and sprinkled with salt.

In order to complete the bridge, the abbot of Tenporin-ji and another senior Yamabushi stand at opposite ends of the bridge and bless it with a complex series of hand gestures. They repeat this at each corner and side until the whole bridge has been consecrated.

Finally, Katsuragi Koryu-san, the abbot of Tenporin-ji, approaches the far end of the bridge. Then, with hands pressed together, he steps up onto the blisteringly hot logs and walks slowly across before stepping down onto the salt and bowing in front of the statue of O-Fudo-Myo-o-sama.

Once the abbot has completed his Hiwatari (fire walk), the rest of the Yamabushi take it in turns to cross the logs and bow in front of the statue. While the Yamabushi slowly file across the burning bridge, all of the festival spectators who are brave enough, take off their shoes and socks and fall in line behind the monks. It can take a while for the Hiwatari to finish as over 100 people often take part.

The Hiwatari is an important part of the festival as walking on fire is a way to ritualistically purify yourself. In the two years since the festival restarted after Covid, spectators have jumped at the chance to take part, with almost every single person in attendance crossing the logs. It also reflects the Yamabushi quest to attain Genriki, or supernatural powers, with the ability to walk on fire (or sometimes swords) without injury being a common power.

My Own Experience

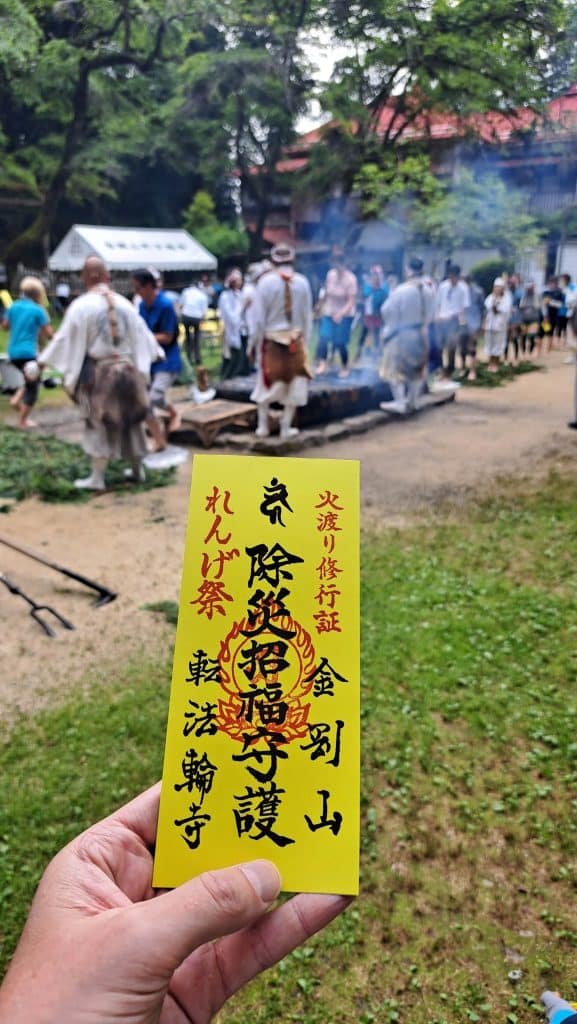

I myself have taken part for the last two years too and I admit that I was slightly nervous the first time. As I approached the step up onto the burning logs, one of the attending Yamabushi handed me a yellow card covered in Japanese script. This was an Ofuda, a charm representing the purification and protection I would earn by crossing the fire. Then, two monks took my hands and guided me up on to the logs and helped me as I walked across as quickly as I could.

I completed my first Hiwatari in 2022, the first year it restarted after Covid. The logs were extremely hot and at times, the fire underneath would whip up with the wind. This happened as I got to the middle point and the flames rose so high that they burned off most of the hair on my legs (I, perhaps foolishly, had elected to wear shorts).

Every step was also quite painful on the feet. Fortunately, I do so much walking that my soles have toughened over the years. The pain was bearable and I made it across with a single small blister. Some participants struggled though, especially those who put their whole foot down on the logs and seared their sensitive arches. Not ideal when you still have to hike back down a 1,200m mountain.

Upon reaching the far end, I stepped down onto the salt and paid my respects by bowing to the statue of O-Fudo-Myo-sama and went to retrieve my shoes. Many of the other participants, especially those who had hurt their feet, elected to cool them off in large trays of cold water that the Yamabushi had prepared and some of the monks were offering blister cream just in case.

For my second Hiwatari in 2023, I was perhaps a little more nervous as it got close to my turn because the memory of the previous year was at the forefront of my mind. But as I stepped up onto the first log, it didn’t feel nearly as hot and I could walk across at an even pace.

Attending the Festival

For people wishing to watch and take part in this fascinating festival themselves, a very early start would be required. From Namba Station, it takes around 40 minutes by train to reach either Kawachinagano Station on the Nankai Koya Line. Alternatively you can take the Kintetsu Nagano / Minami-Osaka Line from Osaka-Abenobashi Station to Tondabayashi Station, also taking about 40 minutes.

Both of these stations have a regular bus service to Mount Kongo, both taking around 30 minutes. This would then be followed by around a 2 hour hike to the top of the mountain depending on your pace.

Alternatively, you could save some time by finding accommodation closer to Kawachinagano or Tondabayashi Stations. A good example would be Amami Onsen Nanten-en, a traditional ryokan in the village of Amami which is only 10 minutes by train from Kawachinagano Station.

Both attending the festival and the fire walking itself are free of charge and everyone is welcome to watch and take part.

Great post! Japan is at the top of my bucket list so love learning everything I can.

Chloe | The Coconut Atlas

The Golden Route (Tokyo-Kyoto-Osaka-Hiroshima) is fine for first time visitors because it covers a good mix of modern and tradition. But it means it also has the areas that suffer the most overcrowding.

You don’t actually have to stray too far from it to find some amazing places though. This temple can be visited easily as a daytrip from downtown Osaka but if coming for the festival, it’s best to stay nearby given the 12pm start.

Wow, what an incredible ritual to witness and take part in. You’re so brave to participate in the firewalk – I don’t think I’d be able to. Glad it was easier in year two!

Both times I’ve been, around 100 people, not including the monks, took part in the firewalk. It looks a lot scarier than it is!

The second time was almost disappointing because I was feeling some trepidation remembering how hot it was the last time.

A big part of this folk religion is undergoing trials and physical hardships so to get a deeper appreciation and understanding it’s good to let go and get stuck in!