Table of Contents

Hometown Boy

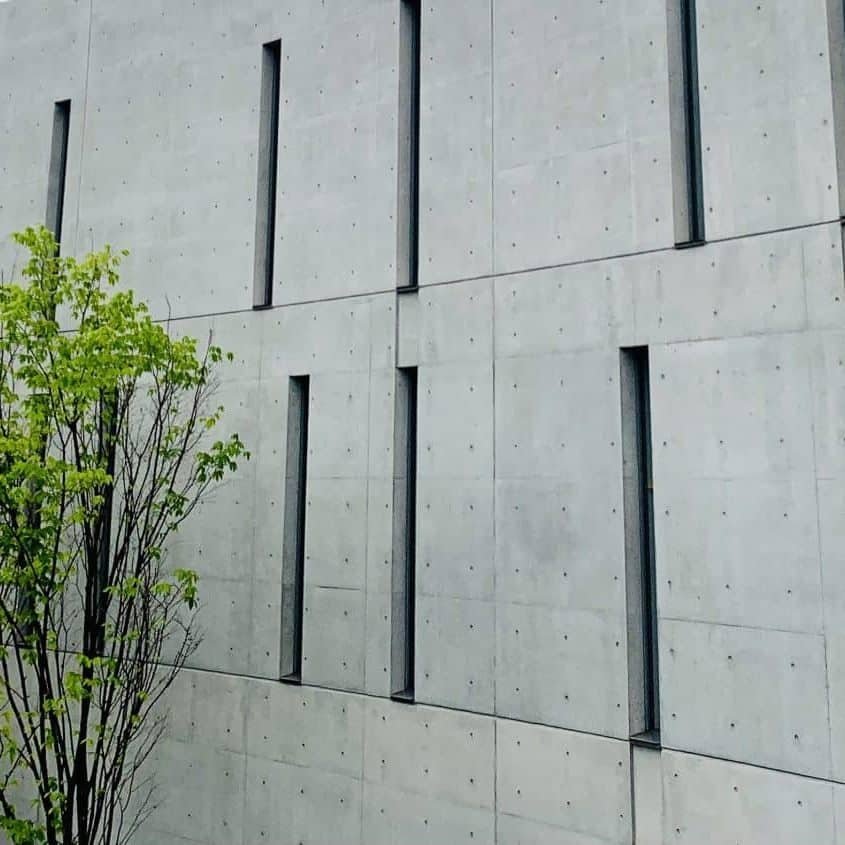

Like exposed brick or old reclaimed lumber, exposed concrete – the kind that comes in smooth, uniform blocks with a couple of dimples in each – is a material with a message. Raw and utilitarian but finely textured, it gives a building gravitas and signals sleek modernity. Even in famously concrete-loving Japan, a well-designed exposed-concrete structure stands out, coming across as architecture, something built to last in a country unfortunately known for its churn of scrap-and-build construction. No Japanese architect is more synonymous with exposed concrete than Osaka native Tadao Ando (b. 1941), who grew up in a working-class neighborhood in the immediate postwar era, fought professionally on the boxing circuit, studied architecture on his own, and rose to international renown. He is equally known for his concern with light, especially of the natural variety, and many of his best-known major works are museums in rural Japan, the US, and Europe. However, he has also carried out numerous projects here in Osaka, many of them small in scale, and his firm Tadao Ando Architects and Associates (established in 1968) has its headquarters in the same Kita Ward location it has occupied for the past half century.

Beginnings

Self-taught architects are few and far between, especially ones that have won architecture’s top award, the Pritzker Prize (in 1995 – he donated the $100,000 prize money to victims of that year’s Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake). With his rags-to-riches story, rough-edged demeanor, somewhat eccentric look topped with a Beatles hairdo, and enduring focus on the local vernacular and street-level experience, Ando comes across as a quintessentially Osakan figure. His roots are in residential architecture, and his origin story began at age 14 when he daily and devotedly observed the guerrilla second-story expansion of his family’s nagaya row house in Asahi Ward.

Another formative teenage experience, during a school trip to Tokyo, was a visit to Frank Lloyd Wright’s (1867-1959) Imperial Hotel (1915, demolished 1968), which famously survived the devastating 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, as all of Ando’s buildings in the vicinity of Kobe made it through the 1995 quake. Another nagaya, Row House in Sumiyoshi (1976, discussed below) was his breakthrough work, though he designed a number of houses prior to it, first venturing outside residential territory by chance in 1973 when his clients had twins and decided they needed more space than his design could provide. He turned the building into his studio, and after repeated expansion and rebuilding, it remains his Osaka HQ. Atelier in Oyodo and Annex (first built in 1973), nestled in a quiet corner of Umeda – they do exist – has signs posted advising visitors that no tours are given and advising them to move along to nearby Chaska Chayamachi (2010), another Ando design containing Japan’s largest bookstore (Maruzen & Junkudo Umeda).

Making a Big Name with Small Dwellings

A few years after his firm moved into its new digs, Ando’s career took off with the aforementioned Row House in Sumiyoshi (still occupied, precise location confidential and no photo here, unfortunately). Like Ando’s own childhood home, the site was the middle house in a row of three nagaya, and the client wanted it rebuilt as something completely different, a space that might not be in Japan at all. This was achieved with a windowless facade, and the plot is divided into three parts from front to back, the center section being a mostly roofless courtyard providing air and light. Perhaps inspired by the light that poured in from above when his family home had its roof removed to add a second story, he designed this courtyard so it needs to be crossed to get from living room to kitchen or bedroom to bathroom, and an umbrella is a must, while winters can be quite harsh.

A central paradox of Ando’s practice is already present in this small, early masterwork: the pragmatism of exposed concrete and simple geometric volumes vs. the prioritization of natural light, air flow, and connectedness with nature, even at the expense of comfort. His responses to concerns have been paradoxical too. He reportedly advised the resident some years ago to put a roof over the central courtyard, but was told there was no turning back now after surviving it this long. Meanwhile, Ando reacted to complaints about the winter cold by telling the resident to get more exercise.

Echoes of Row House in Sumiyoshi can be seen in a more recent residential project, House in Utsubo Park (2010), not technically “in” that lush park in Nishi Ward but with a rear side facing onto it. While larger than a nagaya row house, its site is a similar narrow but deep so-called unagi no nedoko (eel’s nest), and the facade is divided into three parts top to bottom with a void in the center, as if the Sumiyoshi floor plan had been rotated vertically. Utsubo Park stands out from other Osaka parks for its long, narrow footprint––while eel’s-nest houses are said to be the result of Edo Period (1603-1868) laws that taxed property by the width of the frontage, the park owes its shape to its having been an Allied airfield during the 1945-53 occupation––and for its stately and orderly rows of trees. Parkside life looks enviable indeed, and the house manages to capitalize on the fresh air, light, and greenery, while remaining an unassuming and thoroughly modernist box thanks to strategic positioning of apertures.

A Humanist Modernist

Ando apparently has a dog named Le Corbusier, and the pet’s Swiss-French architect namesake (1887-1965) is an obvious and acknowledged influence, as he was for many Japanese architects of Ando’s generation and earlier. A book of Le Corbusier’s works was among his prized possessions during his autodidact years of night classes and correspondence courses. There are notable affinities: allegiance to concrete, clear and sweeping lines, and austere and seemingly self-enclosed buildings with interiors that are surprisingly focused on natural light and views of the outdoors, as well as the fact that both architects were self-taught. Among the principles Le Corbusier set forth as central to modern architecture was “free design of the ground plan,” in other words flexible design of layout and architectural framework in response to the site and purpose, rather than seeking to standardize units for efficiency, or place the “function” of engineering considerations over the “form” of people’s lived experience.

While Ando departs from Le Corbusier’s principles in some notable ways, this is a crucial similarity. At the risk of harping on the negative, a lot of public buildings in Japan look as if they probably appeared quite appealing in the architect’s sketch, with nothing around them except some stock imagery of trees and pedestrians, but in reality, nestled shoulder to shoulder with a jumble of other buildings, they end up as bland containers as uninspiring from the outside as they are forgettable on the inside. It seems that Ando’s concern with the totality of the site, its relationship to its surroundings, and people’s engagement with the structure is what won him architecture’s highest prize even while his projects often look modest from the outside. Even a humble row house deserves its own unique design with a combination of philosophical rigor and warm, human flexibility.

Into the Public Sphere

Ando began scaling up in the 1980s with more public projects such as museums, and in the 1990s and 2000s he became the architectural face of the widely hailed rebranding of Naoshima, a sleepy Seto Inland Sea island, as an international contemporary art destination. He designed the subterranean Chichu Art Museum, a hushed space famously lit only by natural light, and several other museums on the island, as well as collaborating with the contemporary artist James Turrell on Minamidera, a former Buddhist temple and part of the Naoshima Art House Project that is a must-see (or must-not-see––find out what that means when you visit). Museums are probably the genre in which he has worked the most internationally. The only example in Osaka City is the former Suntory Museum (1994), renamed Osaka Culturarium at Tempozan after the beverage giant sadly stopped running the museum in 2010 and gifted the building to the city. Ando’s design features a lot more glass than usual, the better to offer bay views. Located next to Kaiyukan Aquarium in Tempozan Harbor Village in Minato Ward, it is today a venue for limited-time exhibitions and events, often relating to manga, anime and other subjects with mass appeal (bring the kids, but be prepared to wait in long lines), as well as restaurants and other facilities.

Speaking of bringing the kids, a recent addition to Osaka’s cultural landscape is Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest in Kita Ward, instantly recognizable from the north side by the giant green apple sculpture that Ando designed, giving shape to his credo expressed in a 2020 interview with Domus magazine: “Apples and people should remain green, unripe and full of spirit to challenge absolutely anything.” At the children’s library, which accepts but does not require reservations (100 visitors with reservations and 50 without accepted per day), children and the adults accompanying them can browse a huge variety of picture books, children’s literature, science and art books and more in a space with a lofty three-story atrium, and soft, warm wood furnishings. Speaking of his motivations for designing and dedicating the facility, Ando recalled that he grew up in an environment where books, art, and culture in general were scarce or nonexistent, and said he wanted to give children the opportunities he lacked.

Maximum number of visitors per day to Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest: 150. Average daily visitors to Universal Studios Japan (USJ): close to 40,000 prior to the pandemic, now creeping back up. Probably the most viewed, if not consciously noticed, Ando project in Osaka is JR Universal City Station (2001), with a ship-inspired design due to its closeness to the water. With a gently arching ceiling, exposed beams, and motifs evoking sails, it’s a bit reminiscent of another transit hub near Osaka Bay designed by a star architect, Renzo Piano’s Kansai International Airport (1994).

Beyond Architecture

An island surrounded by rivers in central Osaka, Nakanoshima has been compared to the Ile de la Cite in Paris. While Ando’s Nakanoshima Project II (1988), an over-the-top proposal for the island’s sweeping transformation into an urban cultural zone, went unbuilt, the city has been moving in the direction of Ando’s vision, opening the long-awaited Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (originally conceived in the early eighties as the Osaka Museum of Modern Art and in the works for decades) in 2022 next to the confusingly similarly named National Museum of Art, Osaka and the Osaka Science Museum, rebuilding the concert and performance space Festival Hall, and beautifying the island as a whole. Ando has contributed directly to another long-term city project aimed at making its many waterways, which have been in varying states of post-industrial decline, more beautiful, accessible, and beneficial to the public.

In 2004 Ando launched a fundraising campaign that raised hundreds of millions of yen to plant thousands of cherry trees along rivers and in parks. He similarly campaigned for donations to build the aforementioned Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest, and was a driving force behind the redevelopment of Osaka Waterfront Park (2010), including a human-made beach and mini-wildlife protection area in Miyakojima Ward near JR Sakuranomiya Station. According to the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, the plan was hatched in 2009 when Ando and then-Osaka Prefecture governor Toru Hashimoto bonded over a desire to swim in the Okawa River. Urban swimming was evidently something of an obsession for Hashimoto, judging by his unrealized plan to turn the Dotonbori River in Minami into an actual public pool rather than a murky canal into which Hanshin Tigers fans leap following the team’s all-too-infrequent championships––that being said, Dotonbori has been cleaned up and construction continues on a promenade beside it extending westward from Sakaisuji Avenue.

While the expanse of sand in Sakuranomiya sees more beach volleyball, wading, and goofing around than actual swimming, it’s a precious oasis reflecting an ideal of Ando’s that extends beyond architecture to the connection of people and nature in city environments. The adjoining wildlife area at the foot of Genpachi Bridge is home to waterfowl, turtles, carp, a heron or two, and an occasional nutria (an “invasive species” from South America resembling a small capybara, originally brought to Japan during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 to provide fur for missions to cold climes), and stopping to observe and engage with the creatures appears to be an important part of many citizens’ routines.

Beyond Osaka City

This article has focused on Ando in Osaka City, but he has several major projects elsewhere in Osaka Prefecture. Literally the most iconic of them (apologies for using two overused words back-to-back there) is Ibaraki Kasugaoka Church (1989), commonly known as the Church of the Light, in Ibaraki City just north of Banpaku Park. I say literally iconic because the cruciform cutout in the wall is indeed a religious icon, and because the striking sight of light penetrating the stark concrete interior makes it one of his most photogenic and oft-referenced works. As a masterful expression of Christian spiritual transcendence by a modernist often described as a minimalist, it’s comparable to the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. Evidently those in charge of the Church of the Light have had enough of Ando fans and the architecturally curious wanting to visit and snap pics (but not worship), as their website states that tours are no longer offered, and that inquiries about media coverage and photography will not receive replies.

Some other large-scale projects in the prefecture are the Chikatsu-Asuka Historical Museum (1994) in Kanan-cho; the Shiba Ryotaro Memorial Museum (2001) in Higashi-Osaka; the Sayamaike Memorial Museum (2001) in Osakasayama; and Sakura Garden Kadoma (opened in 2006 next to Panasonic’s headquarters) and its sister garden in Toyonaka (2009), further examples of his aforementioned dedication to cherry trees. With his recent focus on introducing nature and culture into urban public spaces, the 81-year-old Ando is looking more than ever outside the box. Even as his projects composed of simple and rigorous geometric volumes continue to rise, his vision for Osaka is helping the city outgrow its reputation as a concrete jungle.