Table of Contents

Introduction

Roger Walch is an award-winning Swiss filmmaker who has spent over 27 years in Japan. I first met Walch in 2005 when I was reviewing foreign films about Japan for The Kansai Time Out. There were only a few foreign filmmakers in Kansai at the time, and YouTube did not exist. The only way to see new films was to go to local screenings. Walch had an uncanny ability to bring together all kinds of interesting people, whether they were local artists, famous musicians, casual acquaintances, or strangers he met on the street, and create a film around them.

One of Walch’s other talents as a filmmaker is finding obscure places deep beneath the surface and bringing them to the forefront on screen. I was so taken with some of his early film locations, such as an old dive bar in Kyoto and a family-run ryokan in Shiga, that I made an effort to visit them soon after. Walch shot an experimental film on Nagasaki’s Gunkanjima Island in 2005, despite the fact that it was highly illegal at the time. Six years later, I was in a multiplex watching the 007 film Skyfall when I saw Gunkanjima in all of its glory. It looked familiar because Roger Walch had been there first.

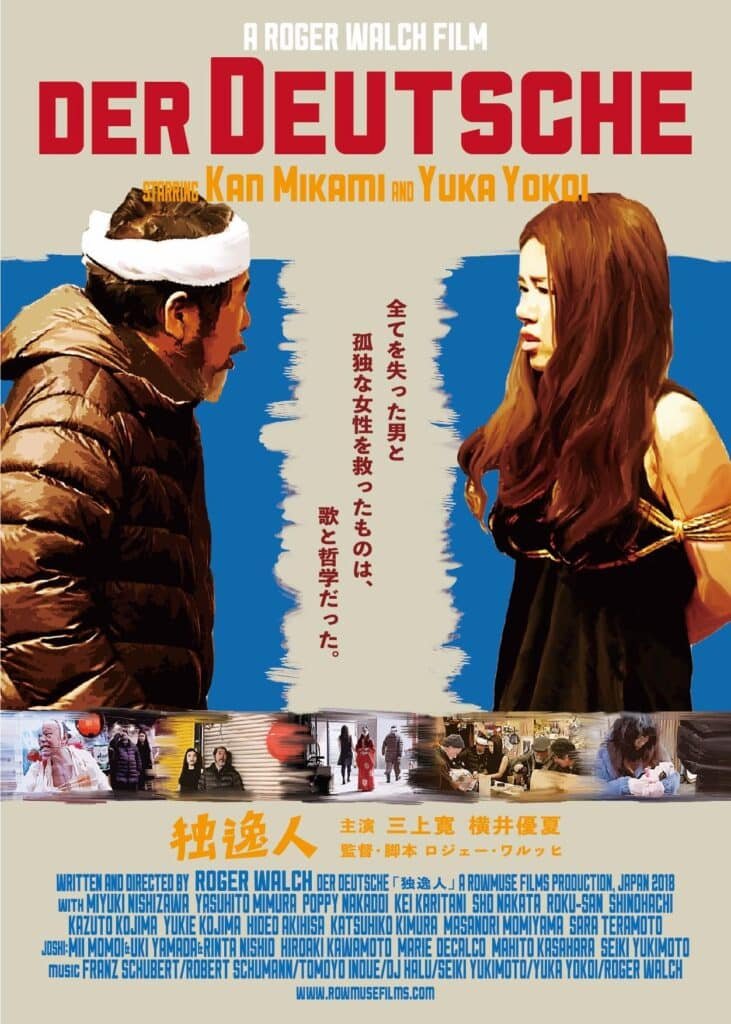

When I ran into Walch five years ago at a concert in a small venue in Osaka, I hadn’t seen any of his films in about a decade. He told me he was going to shoot a new film called The German in Osaka’s Nishinari Ward, starring Mikami Kan, a well-known folk singer and actor who had appeared in films like Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence with David Bowie and Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Osaka is often referred to as “the nation’s kitchen,” but the city also has a wonderful natural cinematic quality that is often overlooked. After attending a screening of The German in 2018, I was greatly impressed with how Walch was able to capture the essence of the city by focusing on the minutiae of daily life, the small details that go unnoticed but create a strong sense of poetic beauty when seen together on screen.

Scroll down to read about Roger Walch’s 9 favorite hangouts in Osaka.

Born in Rorschach ロールシャッハ生まれ

1. Where did you grow up? Describe your hometown.

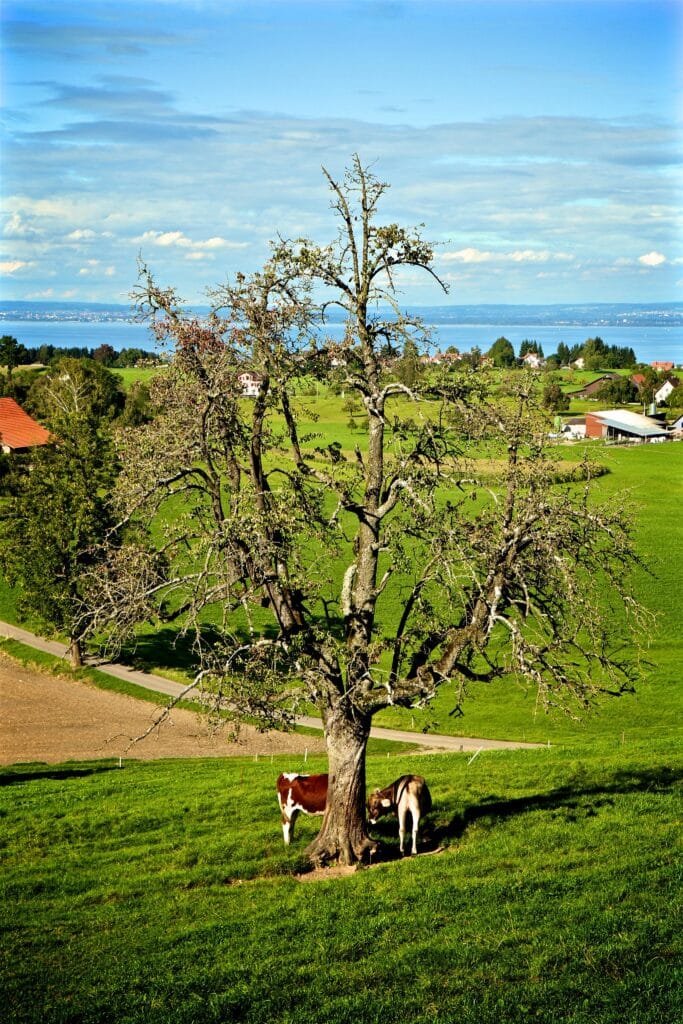

I grew up in Switzerland, in a small city of about 10,000 inhabitants called Rorschach (which by the way has nothing to do with the psychology test of the same name). Rorschach means “area of reed” and is located on Lake Constance, which is about the same size as lake Biwa. It is quite an unusual place for Switzerland for different reasons. E.g. it is not possible to see the Swiss Alps from Rorschach, but instead you have a great view over the lake and its stunning sunsets.

The proximity of Germany and Austria – which also border at the lake – gives it an international feel. As teenagers we would ride our bikes to Austria (a 30 minute ride) because vinyl records, movies and fast food were much cheaper than in Switzerland. Rorschach was founded by Irish monks in the 7th Century and is home of a former Benedictine Abbey which now functions as university of education. Four medieval castles surround the city and stand on nearby hills, a famous granary overlooks the harbor.

A secret underground passageway connected one of the castles with the Abbey and the lake – a secret escape route that would stimulate our imagination when we were kids. Over the centuries this overwhelmingly Catholic city developed into an industrial town with a variety of different factories. That is the reason why almost half of Rorschach’s population nowadays is foreign. When I was a kid, it was the city with the highest rate of foreign population in Switzerland. My classmates were from Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Turkey.

2. Were both of your parents born in Switzerland?

As a matter of fact, both my parents were immigrants. My mother was born in Hungary and fled to Germany with her family after my grandfather was able to escape from the Russian gulag in 1948. My father was originally from France. Son of a single mother, he grew up in Basle where my grandmother worked in a factory. When he was 26 years old he had to become a Swiss citizen in order to be able to obtain his PhD. He then followed a call to become professor for French and Italian at Rorschach’s University of Education. In summer we would go swimming in the lake everyday. The lake was our favorite playground.

3. When did you first develop an interest in Japan?

Because my father was interested in Far East Asia and taught himself to speak Chinese there were many books on China and Japan in our household, especially about gardens and Zen. But it was the TV series Shogun with Richard Chamberlain, Toshiro Mifune and Yoko Shimada that triggered my interest in Japan when I was 15 years old.

Consequently, I read James Clavell’s books, watched Toshiro Mifune in Akira Kurosawa’s movies The Seven Samurai or Rashomon and bought textbooks that explained the Japanese writing system. A couple of years later, a German TV station would air Japanese films every Monday late night. That’s how I learned about directors like Shunji Iwai, Shohei Imamura, Seijun Suzuki, Nagisa Oshima or Shuji Terayama and got completely hooked.

From Switzerland to Japan スイスから日本へ

4. Do you remember your very first day in Japan?

It was in early August 1988 an I arrived on a BA flight from Switzerland via London and Anchorage. I had won a scholarship by the Japan Foundation and was invited to a two week “study tour” through Japan. In the morning I took the bus from Narita Airport to Shinjuku and checked into the Keio Plaza Hotel. The hotel was in one of Japan’s highest skyscrapers and blew me away. Tokyo was shockingly big and overwhelming for a Swiss country boy. In the afternoon I strolled around Kabuki-cho, ate a First Kitchen hamburger and took a lot of photos of skyscrapers, neon signboards and the big screen at the Studio Alta Building – all things that were not existent in Switzerland. I was especially impressed to see a lot of homeless people around Shinjuku station. My legs hurt a lot because I was walking so much on that day.

5. When did you decide to move to Japan?

After three years at university I interrupted my studies to work full time at the post-office for 14 months. I took on all the night shifts and weekend shifts and this way saved a lot of money. Then, in early 1990, I took the plane to Japan. I experienced a four month long homestay in Nara, attended language courses in Kyoto and had a great time hitchhiking all over the country and meeting many interesting people. Of course my Japanese improved a lot along the way. After 16 months I boarded the ferry to Shanghai, spent some time traveling around China and finally took the Trans-Siberian Railway back to Europe.

I had such a blast during my time in Asia that I decided to move there after completing my studies at university. In 1994 I visited Japan again for half a year in order to gather material for my masters thesis. I finally graduated from the University of Zurich in summer 1997.

After having sold all my stuff in a garage sale, I moved to Japan with nothing more than a suitcase in February 1998.

6. What are some of the similarities and differences between Switzerland and Japan?

Surprisingly, the concept of honne (one’s true feelings and thoughts) and tatemae (what you show to others on the surface) is also typical for Switzerland. People often tend not to speak out clearly what they think – especially when they talk about other people. That creates a culture of gossip and “talking behind one’s back”. Switzerland is not an island, but it is a mountainous country and therefore a bit secluded. It doesn’t come as a surprise that Switzerland is not a EU member, the Swiss public voted twice against a membership. Just like the Japanese, Swiss people do not like sarcasm or black humor and hardly appreciate any kind of irony.

Some of the differences I observed are the following: Japanese love a domesticated version of nature in the form of gardens and parks. Swiss people love the real thing – hiking in the woods and in the mountains are immensely popular. Furthermore, Swiss people have been very aware of environmental issues from an early time on. You don’t see a single river flowing in a concrete bed.

Switzerland is famous for the system of direct democracy and the participation of ordinary citizens in political matters. Although there are local referendums in Japan, the results are not binding. People do not talk politics often, whereas Swiss people love to debate all the time, even on a high school or student level.

The Man Who Loved Osaka 大阪を愛した男

7. What was your impression of Osaka the first time you visited? What do you like about the city?

The moment I stepped out of the train I could tell that Osaka has a totally different vibe than Kyoto or Tokyo. It has less to do with the architecture or the sights but with the character of the townsfolk. The people in Osaka are much more direct and open than in other parts of Japan. They are easy to talk to and great companions. It is no wonder than all of my best friends in Japan come from Osaka. And the food is simply great, especially in the cheap local places.

9. Do you have any favorite parts of Osaka?

Generally, I like the South of Osaka more than the North. Many of my favorite places are in Ikuno-ku, Abeno-ku or Nishinari-ku. I just love the atmosphere there. At the start of the 2000’s I had a girlfriend who used to live alone in her grandfather’s house in the middle of Nishinari-ku, not far from Haginochaya Station. It was the time before the 2002 Soccer World Cup, when Kamagasaki still looked and felt a bit like a slum and homeless people were everywhere.

We would regularly go to the famous “Asa no ichi”, which was something like a thieves’ market. The whole area was bristling with activity, the yakuza would organize local gambling events and scores of day laborers would queue up for work every morning. Although the area was feared and had a bad reputation, it was breathing a special kind of freedom. It was the place where red army members would hide from the police and people could easily disappear and live under new identities. Wild times!

9. Why did you choose to live in Kyoto?

As a Japanese studies major, your focus is mainly on the traditional side of Japan. Hence there is an immediate admiration for the imperial city of Kyoto with all its temples, shrines and long history. It was not different in my case. From the beginning on I wanted to stay in Kansai and not in Tokyo. But the main reason why I chose to live in Kyoto was simply that I had good friends there who were about to leave and let me take over their house. I lived in Kyoto until 2012, then we moved out to the countryside where we bought a second-hand house in the South of Kyoto prefecture.

10. Where are you living now?

I relocated to Nara because the rent was cheap and it is quite close to Osaka. It takes less than half an hour from my station to Tsuruhashi or 35 minutes to Namba. I hardly go to Kyoto these days. Most of my friends and hangout places are in Osaka. If I had the means and could afford it, I would move to Osaka right away.

11. What are some other places in Japan that you like?

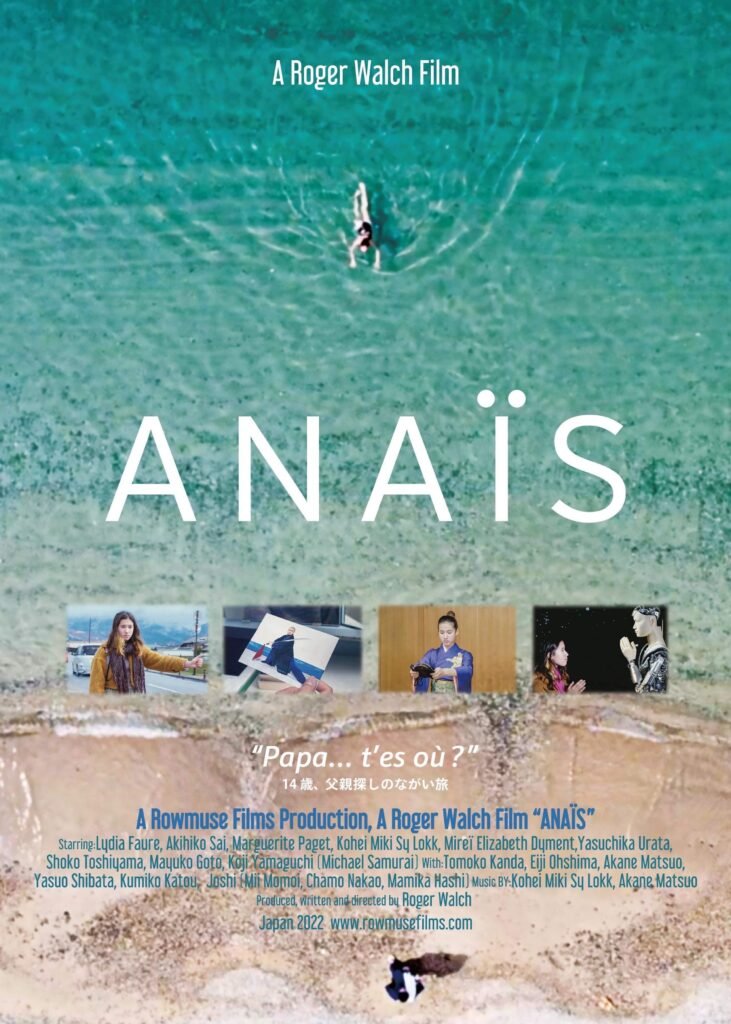

Other favorite places in Japan are the city of Onomichi in Hiroshima prefecture, the city of Nagasaki, the San’in coast along the Japanese sea and the Amami islands between Kagoshima and Okinawa, where I shot half of my film Anaïs.

Confessions of a Filmmaker 映画監督の告白

12. What is your background in film?

I never attended film school. Because my minor was social anthropology at university, I had the chance to enroll in a course called “Introduction to theory and practice of documentary filmmaking”. Later, I became the head of an art house movie-theater in St.Gallen, Switzerland. We screened mostly independent movies and movies that the big cinema chains would not show. We had a monthly program and especially put emphasis on female directors, documentary films, local productions and films that dealt with social issues. We also screened a lot of Japanese movies for the the first time in Switzerland.

After my relocation to Japan, I missed the medium of film so much that I enrolled in a 16mm film course at the Image Forum Institute in Shibuya in summer 2001 under director Kanai Katsu. In groups of five, we would write a script, and each group would realize a short-film, using an old Arriflex camera. I was the only foreigner in the course and was quite surprised how gory and erotic some of the scripts were. Our own film told the story of a young girl who adored the beauty of death. She would randomly shoot people and take photos of the corpses. Not satisfied with the photos, she would eventually shoot herself and take the perfect picture at the moment of her own death. Because my script was not chosen by the group, I turned it into my very first short-film which I shot in 2002.

13. When did you become a professional filmmaker?

In the beginning, filmmaking was rather a hobby. But more and more people asked me to shoot their music videos or document their weddings or even make corporate videos. In 2005 I was chosen as film director to represent Switzerland in the international “Friendship Film Festival” at the Aichi Expo 2005 and won the Special Prize of the Jury (shoreisho) for a documentary on the theme of “Friendship”. This marked the beginning of my career as professional film director. In the years after the expo I realized a couple of projects for municipalities and government entities of Aichi prefecture, e.g. I documented famous shrine festivals (matsuri), shot educational videos and shot a documentary about a famous Aichi photographer.

14. What was the first film you shot in Japan?

The first film I shot and directed in Japan was called Yuwaku 1 and was only 18 minutes long. The story was quite simple: A young disillusioned man gets lured out into the forest by a female ghost and joins a tea-ceremony and dance event held by Japanese spirits. In spite of being unhappy in his actual life he really enjoys the company of the ghosts and decides to stay. For the film we transported tatami mats from my house up to the mountains to create an open air tea ceremony space.

All the participants were wearing Kimono, many were also wearing masks. Most of the actors and helpers were people I had met at Kyoto’s legendary Café Honyarado (which sadly burnt down some 10 years ago). When I came back from the 16mm film course in Tokyo in 2001, I told my friends at Honyarado about my script, and they suggested we should make the film happen. Invigorated by their positive response, I immediately started to make preparations.

15. Were there any particular challenges in making this film?

One of the most daring scenes took place on Osaka’s busiest pedestrian crossing between Hankyu Umeda and JR Osaka stations. One of the female spirits (she was wearing a red kimono with the knot of the obi tied on the front in order to identify her as a ghost) was dancing in the middle of one of Osaka’s busiest roads, while cars and buses and trucks on both sides passed her. But she just continued to perform a slow traditional Nihon Buyo Dance, unaffected by all the traffic and noise. When the pedestrian lights finally turned green, she slowly disappeared into the crowd.

16. Would you do anything differently today?

The film was shot on a cheap low-resolution digital video camera. Because I didn’t have any audio equipment, I just used narration and music to illustrate the scenes. Nara based band Shamion provided some of the soundtrack, the rest of the music I programmed on my synthesizer.

At that time I had no idea about post-production or grading. In order to be able to edit the short-film I bought a copy of Apple’s Final Cut Pro editing software. Although I was very proud of my achievement, and held a big film premiere on the second floor of Honyarado in 2002, the film was so amateurish and bad that I’m too embarrassed to show it anymore. (Actually I think that I only have a copy on an old VHS-S tape somewhere in a cardboard box).

But the film started my Yuwaku trilogy on the theme of seduction. Working with friends and using cool existing locations proved to be a good recipe. It showed me that it is possible to shoot a movie with a very limited budget. My next short, Yuwaku 2, was already nominated for best film in Osaka’s CO2 film festival in 2004. And Yuwaku 3 (2006) got quite good reviews at a couple of festivals. I was basically learning while doing and trying to up the game each time. It was a long, slow but ultimately fun process. I had to teach myself how to operate a camera, how to direct actors, and how to edit and score the film. Technology was advancing a lot during that time, e.g. high definition video came out and YouTube was launched.

17. Is shooting a film in Osaka different from shooting in Tokyo?

Since 2005 I have been shooting movies and TV content professionally all over Japan. I worked as DOP for Swiss, German and British directors, shot content for French, German and Swiss TV stations and also shot interviews for the BBC. Generally the same rules apply wherever you run a camera in Japan. For me the big difference between shooting film in Tokyo and in Osaka is the relationship with the people you work with.

Tokyo is a very regulated and professional environment when it comes to filmmaking. You have to set up meetings, present scripts and shooting schedules, organize permits and often work together with an agency or local producers. I feel more free when I film a movie in Osaka. I normally ask people and shops directly for a shooting permit and don’t have to go through agencies. It is about mutual trust and respect.

On Location in Gunkanjima (years before 007 in Skyfall)

18. What was it like shooting Lost Island on Gunkanjima?

It was forbidden to visit in 2005 so I had to bribe two fisherman to bring me there. The boat could only land at high tide and we basically only had a couple of hours until they would pick us up again. Actually, it was pretty dangerous because sometimes debris would fall down from the upper floors, or roofs would collapse. I have no idea if I was the first filmmaker to shoot a movie there.

Gunkanjima has since become a Unesco World Heritage Site and a tourist attraction. It is quite expensive, and the people are guided and have to stay on safe walkways. They are not allowed to walk between the buildings. Gunkanjima was the most densely populated spot on the earth back in the day and Japan’s first concrete buildings were erected there. It is indeed a spectacular place that breathes history and also tells the story of slave labor and corporate greed.

19. How did find actors to appear in your early films?

I couldn’t afford to hire professional actors for my early films. That’s why I often asked friends and acquaintances to appear in my movies. Sometimes I would even approach total strangers in a café or in the street.

The secret when using non-actors is to use their everyday personality and not to rely on (mostly non-existent) acting skills. I would only cast people who would fit a certain role perfectly. In this way, they more or less just have to be themselves and don’t really need to act or pretend to be someone else. But it takes a sharp eye, and some people do not feel comfortable in front of the camera. Because non-actors sometimes have difficulties in remembering lines and get confused by long scripts, I often let them improvise in order to get a natural result.

Working with professional actors takes a totally different approach. Actors learn their lines by heart and make a big effort to portray a certain role in the film. They are used to being directed and move naturally in front of a lens. The problem with professional actors is that they sometimes expect strict guidance. That makes improvisation sometimes difficult. But of course it always depends on the actor.

My Friend Mikami Kan 友人の三上寛さん

20: How did you meet Mikami Kan?

In May 2004 my short film Yuwaku 2 was screened at the Tokyo’s Design Festa. After the screening I was scouted by Hideki Masahiko, the organizer of Tokyo’s legendary Underground Festivals Angura and Chikashitsu. He invited me to show my film at the next Chikashitsu event where Mikami Kan would perform as headliner. After the Chikashitsu screening, Mikami Kan approached me backstage and said: “You like Terayama Shuji, don’t you!” I nodded, and we started to talk about Terayama Shuji. We immediately clicked and continued our conversation until well after the event. That’s how our friendship began.

21. How did the documentary you shot about Mikami Kan come about?

For the next couple of years we would both always appear in both the Chikashitsu and Angura events in Tokyo and at one of the gatherings. Mikami Kan suggested, that we should do a film together. I had the idea to make a documentary about his relationship to his mentor and biggest influence: playwright and poet Terayama Shuji.

So I started to film Mikami Kan in 2005 and followed him with my camera all over the place. This continued for a couple of years. We visited Terayama Shuji’s grave, went to Aomori together and I documented countless concerts in different clubs and live spots all over the country. It was a special honor to join him on his 2012 tour through Northern Japan and crash at the same accomodations after the shows.

Although he was notorious for being a heavy drinker and a womanizer, I got to know all his sides. In my opinion, he is foremost a poet and philosopher with a very sharp observing eye. The film eventually came out in 2013, it was screened at the Tama Film Festival and had a run at independent movie theaters in Tokyo and Osaka. Mikami Kan also starred in my movie Tengu in 2009.

The German Der Deutsche 独逸人

Read Osaka.com film critic Johannes Schonherr’s review of The German here

22. How did you get the idea for The German?

While promoting the documentary, Mikami strongly suggested that we should do another movie together and urged me to write a script. My brain immediately began to spin. Contrary to what many people think, I’m far from being a botchan (a spoiled rich kid) and always struggle to finance my films. The key to keep the costs low is to have a script with only a few actors and great (free) locations. A good example is Jacques Rivette’s French film La Belle Noiseuse with Michel Piccoli and Emmanuelle Béart – a film that focuses on the relationship between an older painter and his young model. The premise of that film served as an inspiration for The German.

Because I consider Mikami Kan to be a philosopher, I had the idea to cast him as one and pair him with a young opera singer that I had worked with on my latest CD. And because I had always wanted to shoot a film in Osaka’s notorious homeless district Kamagasaki, I quickly decided to have him play a homeless philosopher. I talked with Mikami Kan about this idea and he suggested that he should be speaking in the philosophers’ language: German. I asked him if he was serious, but he was dead-earnest.

23. Was it difficult for Mikami Kan to learn his lines in German?

Although he is an excellent actor who usually almost only delivers first takes and is renowned for remembering even long and complex lines, he struggled with the German pronunciation and we had to do many after-recording sessions to get his lines right. When I started to write the script I promised that his lines would be very short and limited…a promise that I eventually broke (laughs). Little did I know that he would struggle so much with the German pronunciation and that the shooting and editing process would take so much longer than anticipated.

Filming in Nishinari 西成での撮影 Filmaufnahmen in Nishinari

24. The German was filmed in the Kamagasaki area of Nishinari. What was it like shooting there?

Everybody warned me to shoot a film in Kamagasaki, among the yakuza and homeless. People had heard horror stories about riots and violence and avoided the place. I have been familiar with Nishinari since the late 90’s and regularly visited the place. I never felt threatened or in any danger. On the contrary I became friends with a lot of people there. For The German I started to go alone for B-Roll and scenic shots long before the actual film shooting.

Somehow I became a familiar sight, wandering the Nishinari back alleys equipped with my big camera and my tripod. People would approach me and start to talk or ask question about my intentions. They were worried that I would film their faces and expose their hidden identities. But they always quickly calmed down when I explained my motives. Some of the homeless then even wanted to join the movie and some of them actually appear in the film.

The first big scene I filmed with actors was the dance group Joshi in a park. We bought big cases of Japanese sake and invited everybody to watch the film shooting. We got a big crowd watching from behind the camera, and everybody was happy. From then on everybody knew who I was and greeted me whenever they saw me. Even today people recognize me and come talking about the film.

25. Did you run into any problems during the shoot?

There was an incident involving an angry drunk youngster who didn’t like the idea that a foreigner was filming what seemed to be some yakuza pushing a blindfolded girl out of a car. He started to talk to me very aggressively and called the police while he was shouting at me. Sure enough a couple of minutes later three policemen showed up and asked us to present a shooting permit or leave. Mikami Kan tried to explain that it was a non-profit independent film production and shooting would wrap up soon anyway. Although they were sympathetic, their hands were bound because someone had filed a complaint. So they had to act. The local people who were observing the film shooting from their windows and knew Mikami Kan recommended that we should just pretend to leave and then come back and finish the shooting. And that’s exactly what we did.

26. Did The German screen in any German-speaking countries. What was the reaction?

In summer 2018 I screened “The German” in Switzerland and had two sold-out shows. Even the Swiss newspaper ran a big story about the film. To my surprise a lot of distinguished well-dressed Opera lovers showed up, which actually had me really worried. It is true that The German is in fact a musical. The lead actress, Yokoi Yuka, performs a couple of Schubert and Schumann Lieder during the movie. But I was afraid that the neat and clean Swiss Opera aficionados would be shocked about the conditions in Nishinari and the overall underground feel of the movie. However after the screening the whole audience stayed on for the Q&A session and was really enthusiastic. To my big relief the film was really well received and a lot of people asked for additional screenings. They were especially charmed by the vocal and acting skills of the young actress and also impressed by Mikami Kan’s portrayal of a philosopher.

The Making of Anaïs メイキング・オブ・アナイス La création d’Anaïs

27. What made you decide to do a film in French (Anaïs) after The German?

Lydia Faure, the 14 year old daughter of a longtime French friend was starring as the lead actress in a contemporary Japanese theater play. Curious, I went to see her performance and was blown away by her charisma and talent. Furthermore I learned that she had been practicing Noh theatre acting since age 3. Upon hearing my positive reaction, her father jokingly suggested that I should write a movie for her.

After some brain storming, I came up with the idea for a road-movie. Once I consulted with Lydia Faure directly, I started with the script. Of course I wanted to include some Noh scenes and also address certain problems that children of mixed parents face. By running away from home (from her French mother), and looking for her Japanese father she also starts the process of finding her own identity.

28. How did you cast the main roles?

First of all I had to find good actors to play the parents. I was very lucky to cast Marguerite Paget and Sai Akihiko as parents. They both did a very convincing and terrific job. Marguerite was recommended to me by some Kyoto friends, she is very active and respected in the French community. I had known Sai, who is mainly known as a martial arts actor (he was in movies like Resident Evil, Kate, High and Low II and The Last Samurai), from a commercial shoot in Kobe some years ago. I always wanted to work with him. In Anaïs he was able to show both his sides, his stunning martial art skills and his soft side as a caring father.

Fabulous artist Toshiyama Shoko is in the film. She is known as a poet, musician and photographer and has collaborated with Mikami Kan in the past. In the film she plays the former lover of Anaïs’ father and is surrounded by her own artwork. She is lovely and very charismatic, I’d love to work more with her. By the way, Sai Akihiko’s wife is also in the movie. She is a former body building champion and still works out, she is very impressive.

Lydia’s Noh teacher, famous Noh actor Urata Yasuchika from the Kanze Noh school, let us film in his house and plays the instructor. He provided all the Noh costumes and the masks. Another actor in the film is Yamaguchi Koji. They call him Michael Samurai because he does Michael Jackson’s moon dance in full samurai armor. He often plays in jidaigeki (samurai dramas) and is a regular on TV.

29. What has the reaction been like at screenings of Anaïs, so far?

People seem to like the film very much. The coming-of-age story of the 14 year old girl on the quest to find her father resonates with the people. The film shows different landscapes and the beauty of various parts of Japan. It starts out in the city and ends on Amami Ohshima island, but no paradise comes without its hiccups. I was approached by a distribution company, and organizations like the Institut Français, the Fête de la Francophonie and the Swiss Embassy want to screen the film. [Note: Screenings with English subtitles are set for beginning of 2023.

30. How many languages do you speak? Do you feel differently when you are speaking each language?

In order of ability: German, English, Japanese, French and some Italian. Each language comes with a different set of cultural background. When I speak Japanese I use a lot of aizuchi (non verbal utterings) and a lot of body language like bowing and nodding. Whenever I’m back in Switzerland and talk on the phone with some Japanese, the Swiss people around me roll on the floor laughing because my whole body language and behavior is so different from what they are used to. Normally I dream in German, but I had dreams where I spoke Japanese or English.

31. How do you go about writing your scripts, especially since your films are multilingual?

I honestly don’t know what drives me to shoot movies in different languages. As I mentioned previously, Mikami Kan had to speak German and quote German philosophers throughout The German. Anaïs is half in French, half in Japanese. It helped very much that I can speak and write all three languages. But working in different languages always means a lot of extra work with subtitles and multilingual script writing.

一位瑞士導演喺香港拍攝了一部電影,但佢唔會講廣東話。

32. Has this multilingual approach ever caused any difficulties?

In 2018 I shot a drama called The Rooftop in Hong Kong’s Yau Ma Tei district. I had written the script in English, but the language of the film was Cantonese, which I cannot speak. Therefore I hired a translator who created a Cantonese script. However, the main obstacle was that the main actress could only speak Mandarin and Japanese. So we needed a language coach in order for her to master the difficult Cantonese pronunciation, and we also had to simplify some of the lines because they were too difficult for her.

Editing proved to be a nightmare because I can neither understand Cantonese nor Mandarin and some of the scenes’ dialogues differed from the original script. For that reason and because I still need to reshoot some scenes, the film has yet to see the light of day (Covid and the political situation in Hong Kong didn’t help, either).

33. You mentioned some of your favorite Japanese filmmakers earlier. Any other directors who have influenced you?

I grew up in Europe watching films by directors like François Truffaut, Federico Fellini, Luis Buñuel, Louis Malle, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders or Rainer Werner Fassbinder. I was always fascinated by films with a surreal touch, especially by Buñuel and Fellini. It is very interesting in this context to mention that Terayama Shuji was heavily impressed by Fellini’s film La Strada which was the inspiration to his film Den’en ni shisu (To Die in the Country).

34. What are some of your future projects?

I just finished directing and shooting a seven part documentary series about Noh Theater. It will be on Amazon Prime next month. Another series about Kyoto’s Daigoji Temple is in the making. Because JR Tokai was one of the producers, the series will also be streamed in Shinkansen trains. Together with English producer Andrew Thomas and well-known scholar Alex Kerr I’m also working on a nine part series on Alex Kerr’s book Another Kyoto. Shooting is almost finished. We hope to bring the series out by Spring 2023.

Currently I’m in the process of writing a script for my next movie, a hard-boiled detective story that takes place in deep Osaka. I cast Sai Akihiko in the lead role. He is a really talented actor and we became good friends when we were shooting Anaïs together. We share the same vision which makes working together with him very easy. His expertise as fight coordinator and weapons’ handler will also come in handy for this project. Hopefully, Mikami Kan can play a small role in this film. I would like to be able to start filming in Osaka next year and incorporate a lot of our favorite locations. It will be great fun!

35. Is it difficult to get distribution in Japan as an independent filmmaker?

Yes, it is quite difficult. Most Japanese directors only get distributing deals after they have won a prestigious film festival abroad. This is especially true for independent productions. The Japanese market is limited and the industry focuses on blockbusters or popular Anime for children. I was lucky that I was approached by a Japanese distributor for Anaïs. But because of the pandemic many cinemas and distribution companies have a large back catalogue of films that they were not able to screen during the lockdown. So it will take time.

36. You’ve also shot stuff for the Goethe Institute, right?

The Goethe Institute is a non profit German cultural organization run by the German government, promoting the German language and Germany-related cultural activities and events. I shot 36 artist videos for their artist-in-residence program at the Villa Kamogawa in Kyoto. I also shot 10 commercials for the Goethe Institute that are still used to promote their language program on social media.

37. How did you get involved in Dragon Film Festival in Osaka?

Dragon Film Festival was created by Osaka based film director Kawamoto Takahiro, who is best known for his film Kaba. Kaba tells the true story of the struggle between teachers and pupils at a local Nishinari high school in 1985. A lot of the students were racially discriminated because they came from the neighboring buraku area or were of Korean descent. Eventually, with the help of two charismatic teachers and the school’s baseball team, things start to look better for everyone.

Dragon Film Festival started as a small showcase for local directors and as a way to collect money for local film production. In the seven years of its existence it has grown into quite a big festival. The first time I was invited was in 2018 with The German. In 2022, no less than 48 local directors participated. Over the course of four days more than 60 movies were screened at Shinsekai Toei movie-theatre. This event is proof that there is a thriving independent film scene in Osaka.

キープ・オン・ロッキン・イン・ザ・フリーワールド

38. What’s your background in music?

From age nine I learned classic piano. But sharing the same birthday with Mozart didn’t help, because my piano teacher always wanted me to focus on Mozart and Bartok (because my mother was of Hungarian descent). My teacher was this strict old lady who also played the pipe organ in the local church and could absolutely not understand my wish to play jazz and more contemporary music. Hence the classic piano lessons developed into something of a nightmare and after five years I quit.

Soon after I quit talking piano lessons, I joined a band and I have been playing in jazz and funk bands ever since. I got completely hooked. I attended the local jazz school, took jazz piano lessons and participated in workshops. Later I won a couple of music competitions with two different bands. Between 1992 and 1997 I played on a semi-pro level, making a couple of CDs and giving about 50 concerts per year. After coming to Japan I immediately joined a band and played the local venues. The older I got the more I was drawn to acoustic music. Since 2002 I have been playing in a duo with Shakuhachi Flutist Matsumoto Taro. We released two CDs and toured around Japan. In 2016 I released my first solo album Broken Cage where I collaborated with three opera singers, a trombonist, a Biwa lute player and shakuhachi flute.

39. Do you score all of your films?

Having a musical background I often composed the soundtrack to my films. Or I used some of my existing compositions to illustrate some scenes. But I also like to ask other musicians. The soundtrack for my newest film Anaïs was mainly composed by Japanese folk musician Kohei Miki Sy Lokk whose talent and songs I really admire. The Kyoto based band Morphic Jukebox provided the soundtrack for my movie Children of Water and Mikami Kan contributed a song for my movie Tengu.

40. Have you performed any memorable concerts in Japan?

I have to mention collaborations with Mikami Kan and Ohtaka Shizuru (Sizzle Ohtaka). As a pianist, I performed two concerts with Mikami Kan, one in an old sake factory in Shiga and the other in a famous Jazz Club in Kobe. Ohtaka Shizuru’s music had been a favorite of mine since I first arrived in Japan. She was best known for her rendition of Kina Shokichi’s song Hana, but she also composed music for anime (such as To The Forest of Firefly Lights or Spirited Away) and video games (Final Fantasy), and she was a regular on NHK’s Nihongo de Asobo. In 2010, I had the honor of accompanying her on three concerts as keyboardist with the band Wakon Yosai. I was devastated to hear that she passed away in September 2022.

Roger Walch’s Osaka: 9 Favorite Hangouts

Shinsekai Toei Cinema (Shinsekai) 新世界東映

Address: 2 Chome-2-8 Ebisuhigashi, Naniwa Ward, Osaka, 556-0002. Tel: 06-6641-8568. Open: Every Day, 9:00 to 25:00.

I have an ulterior motive for suggesting that we start off in Shinsekai. It is the location of the Kokusai Cinema, an old movie theater that is famous for hand painted signs that have attracted international attention. Walch surprises me by choosing the Shinsekai Toei theater instead, which Osaka.com film critic Johannes Schonherr describes as “one of the last old-style grind house movie theaters in Osaka, running their films with almost no interruption around the clock.”

“This gem of a genuine old movie theater was the location for this year’s Dragon Film Festival,” says Walch. “Film aficionados know the place not only for the pink eiga and yakuza flicks it shows, but also for its vast collection of film posters. Hideki Nagamine is running the place and operating the old Fuji Central 35 mm film projectors. It is because of him that Shinsekai Toei houses one of the biggest collection of old film posters in Japan. His archive is legendary, that is the reason why many of Japan’s old movie-theaters would send him their own poster collections before they went out of business.”

Tea Room Combine (Shinsekai) 喫茶コンバイン 新世界

Address: 2-chōme-3-20 Ebisuhigashi, Naniwa Ward, Osaka, 556-0002.

Roger wants to take me to Do Re Mi Coffee, an old shop located next to the Tsutenkaku tower that is famous for pancakes, parfait and a really cheap morning set, but the place is packed with tourists and we can’t get in. “It was a pity that Do Re Mi was full,” says Walch. “I had meetings with Mayuko Goto from Pika Space there about the poster design for The German, and also met [actor] Sai Akihiko there a couple of times to discuss some scenes of Anaïs.

The wonderful thing about this area is that you don’t have to walk far to find another old coffee shop. We decide on Tea Room Combine, which is located directly across from the Shinsekai Toei Theater. I must have walked passed this place a thousand times without going in. The decades old shop is decorated with photos and memorabilia from the Takarazuka Review, an all-female musical theater troupe.

We order two morning sets, which consists of coffee and a slice of thick toast. We could have easily made this breakfast at home, but it rarely tastes as good as when you sit an old neighborhood coffee shop. Each shop has its own history, customers and decor. ¥350 yen for the set is a small price to pay to sit here and soak up the atmosphere before heading out to our next destination.

Taiwanese Restaurant Unryu (Nishinari-ku) 雲隆

Address: 1 Chome-2-27 Taishi, Nishinari Ward, Osaka, 557-0002. Tel: 06-6648-8511. Open every day from 11:00-23:00.

“Whenever I am in Osaka’s Nishinari-ku, I pay a visit to Unryu,” says Walch. “It is well known in the neighborhood for its cheap and delicious Taiwanese and Chinese dishes and therefore well frequented throughout the day. Situated not far from Dobutsuenmae Station Exit 2, its big yellow signboard immediately catches one’s eye. The inside looks neither especially fancy nor picturesque, it is a rather practical place with 20 seats. But the restaurant is open 365 days from 11 am to late at night – even on days with a typhoon warning when all other shops are closed. The Chinese-speaking owners offer a variety of dishes that include Taiwan ramen, sweet and sour pork, mapo tofu or fried rice. Honestly, I can’t get enough of their food. The teishoku (set meals) are a treat and well worth the money.”

I order the Taiwanese ramen set (¥780), which comes with your choice of fried rice, mapo tofu or tenshinhan. Trust me, go with the tenshinhan because the portion is huge for a side dish—it’s almost like getting two meals for the price of one. Roger decides on the mapo tofu set (¥680), which comes with soup, rice, a spring roll and kimchi.

Coincidentally, a Taiwanese night market festival is being held in front of a hotel in Shinsekai with lines around the block. However, I have found that you have to be careful when going to Taiwanese restaurants in Japan. The food is often watered down because many Japanese do not like the taste of star anise—a key ingredient in Taiwanese cooking. If you order the excellent yakisoba here make sure to ask for “Taiwan-fu yakisoba” so you can experience the authentic taste. My ramen was just how I remember having it in Taipei several years ago.

Earth Cafe (Nishinari-ku)

Address: 1 Chome-3-26 Taishi, Nishinari Ward, Osaka, 557-0002. Tel: 070-1340-1212. Open every day from 12:00-23:30 Facebook

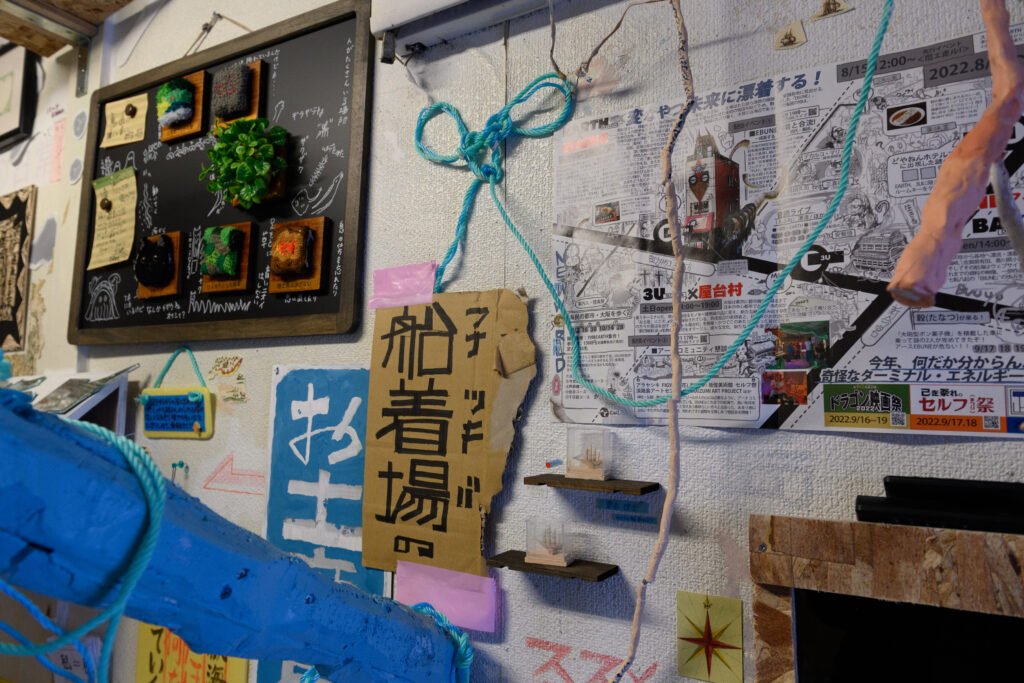

After lunch we walk a block down to EARTH. I have always been curious about this place but have never ventured in.

“This is the center of cultural activity in Osaka’s Nishinari-ku,” explains Walch. Although small, EARTH is at the same time café, gallery, theater and live music space. It is a hangout for filmmakers, artists and homeless people. Terakawa Daichi, who runs the place is a charismatic selfless guy with a good heart and a huge knowledge. He is supporting local artists and helps wherever he can. He also makes one the best espressos in Osaka. EARTH was our home base when we were shooting my movies The German and Anaïs in Nishinari-ku and Shinsekai in 2017 and 2020.”

We poke our heads in but the owner, Terakawa, isn’t in. I suggest that we come back later, but Walch insists that it won’t be a problem at all. The walls of the tiny cafe are filled with artwork and crafts, some of which appear to be for sale. Is Earth a cafe in an art gallery or an art gallery in a cafe. I don’t know, but I like it, like it, yes I do. I would love to come back to Earth and hang out with some of the regulars .

“The open-minded spirit of this cafe attracts a lot of interesting people,” says Walch “Well-known Osaka documentary director Takeda Tomokazu is a regular, female artist Kouryou has turned the place into the headquarters of the Ebune Art Festival, and Butoh dancer Decalco Marie always gives a spectacular performance in front of EARTH at sunset on the second Saturday of each month.”

Terakawa finally appears. He is a laid-back guy with long hair and a beard. He explains that he has been running back and forth between Earth and 3U, another art space down the block. It is a beautiful day so we decide to sit outside at a small table on the sidewalk. We order two espressos from the famous machine inside. I also ask for a bottle of Kirin Heartland, which Terakawa brings me right away.

Walch starts to tell me a very entertaining story about an eccentric person he encountered in Europe many years ago. By the end of the story, I had downed most of my beer but the espressos still hadn’t arrived. We were having a great time talking and didn’t mind at all, Shortly after, a young man approached our table with three coffees from a nearby Family Mart. He apologized for the delay and explained that Terakawa was busy trying to fix the famous espresso machine, so these coffees were on the house.

About 10 minutes later, Terakawa came out holding two freshly-made espressos, and announced that he had fixed the machine. He said that there would be no charge for everything, including my beer, because of the wait. Walch had told me earlier that Terakawa often lets homeless people drink coffee at the cafe for free, so we refused his very generous offer. Even if that weren’t the case, we still would have insisted on paying. It’s important to support local businesses during these tough times.

3U Asylum (Nishinari-ku) 3Uアジール

Address: 1-chōme-4-20 Haginochaya, Nishinari Ward, Osaka, 557-0004. Open: 14:00-19:00

Roger Walch on top of the world at 3U Asylum. Photo: Tsuyoshi Tagawa

Having had a great time at EARTH, I was now looking forward to visiting, 3U Asylum, an art and performance space that has strong ties to the cafe.

“3U Asylum, is located at a prime location right across JR Shinimamiya station,” says Walch. “It used to be a business hotel, but after the hotel closed, the building stood empty for quite some time. Because the local owner is an art lover, he offered the empty space to the local community so that it could be used for cultural events. The spacious first and second floors were consequently transformed into cool art and exhibition spaces. Theater plays, concerts, film screenings and art exhibitions have been taken place ever since. My movie Anaïs had its Osaka premiere at this venue.

3U Asylum was also the main venue for this year’s Ebune Art Festival of Contemporary Art. I wanted to know more about the origins of this festivals so we spoke to one of the organizers, the aforementioned artist Kouryou.

“Japan once had a seafaring people known as ebune (家船),” says Kouryou. “They moved around East Asia, living aboard boats with their families, unintentionally bringing different cultures together, and building networks. They must have had a significant impact on the development of Japanese culture. EBUNE, a group of modern artists from throughout the country, started drifting by relying on their traces found in the ancient layers of history. They are creating an unknowable narrative as they repeatedly wander in the direction of life.”

“The area where EBUNE has washed ashore has also grown significantly to include Nishinari,” she continues. “The expressionists of this region congregate in EARTH, a building, which is connected with EBUNE. Various artists display and sell their works at the souvenir shop on the first floor of the landing as “souvenirs that you want to take on your voyage.” Passing through the torii gate at the end of the landing and boarding the EBUNE, visitors can experience a boat trip that is like wandering through the social structure created by the human mind.”

“The “3U Asylum Yatai Mura” was held at right here in this abandoned building, “Mansion Sanyu,” Kouryou elaborates. “Booths were set up by art communities and shops from all over Japan that EBUNE has interacted with on its voyages, as well as institutions and spaces in the region that EBUNE has created alongside the Nishinari drifters that have washed ashore. Visitors could peruse the booths and buy items that represent the characteristics of each activity. On weekends and holidays, live performances were held onstage for a pay-what-you wish fee. Other events have included a walking tour of the city with a guide to explore the forgotten history, culture and stories that lie in this area, and a talk event given by various expressionists, art professionals, and researchers.”

Taiyoshi Hyakuban (Nishinari-ku) 鯛よし百番

Address: 3-Chome-5-25 Sanno, Nishinari Ward, Osaka, 557-0001. Tel: 06-6632-0050. Currently undergoing renovations

After leaving 3U Asylum, we walk through the Tobita Hondori Shotengai, which was founded in 1916, towards Osaka’s famous red light district to visit Taiyoshi Hyakuban a century-old former brothel that was turned into a very popular restaurant. Taiyoshi Hyakuban is currently undergoing renovations to restore this registered tangible cultural property to its former glory. Over 19 million yen ($135,000) has be raised so far through crowdfunding.

“Although Osaka’s red light district Tobita Shinchi has a notorious image and is a no go for the average Osaka citizen,” says Walch. “There is one place that is safe, spectacular and beautiful at the same time: Taiyoshi Hyakuban. This architectural gem from 1918 in the Taisho Era is a former 21-room brothel. Its rooms and sliding doors are richly decorated with paintings and ornaments of the time, its outside is illuminated by red lanterns at night. Food-wise it offers onabe, different styles of hot pots. I have been enjoying the chanko nabe there many times since I discovered the place in 1998. It is rare to be able to experience such a genuine time slip and dine in what used to be an original Japanese brothel.”

Tsuruhashi Market Shopping Street (Tsuruhashi) 鶴橋市場商店街

Tsuruhashi Ichiba Shotengai, which consists of six marketplaces and shopping streets, started as a black market in the fall of 1945, shortly after the war ended. Tsuruhashi Station, where the Kintetsu and JR railway lines intersect, has long been a strategic transportation and logistics hub. The fact that those railroads were not destroyed by air raids during the war aided its ability to function as a black market. Several shopping streets were established around 1946, and the prototype for today’s shopping street emerged.

“Since coming to Japan for the first time in 1988, the Korean market around Osaka’s Tsuruhashi station has been fascinating me,” exclaims Walch. Its old arcades and retro feel, the delicious spicy food and the open and chatty character of the market people is a nice contrast to everyday life in Japan. I shot a couple of scenes of my movie The German in the arcades furthest to the East of the market. And I have used it as a photo shoot location for many times.”

Ikuno-Ward (and its immediate surroundings) is home to the largest population of Korean residents in Japan. Tsuruhashi Market Shopping Street appears prominently in the 2017 novel Pachinko by author Min Jin Lee that depicts the 20th-century Korean experience in Japan. The novel was adapted into a television series for Apple TV plus in 2022. Unfortunately, plans to shoot in Osaka were halted due to COVID19 and the market scenes were recreated in Korea and Vancouver, Canada.

Tsuruhashi Koreatown and neighboring Ikuno Koreatown are rapidly changing as a result of an influx of new shops selling the latest KPOP merchandise and restaurants serving popular street food items such as Korean corn dogs to large crowds visitors. At this rate, the older shops with nostalgic hand painted signs won’t be around much longer, but Walch is helping to preserve the area’s legacy on film.

Tori Ichiban Honpo とり一番本舗ナンバ店

Address: 1 Chome-4-11 Nanbanaka, Naniwa Ward, Osaka, 556-0011. Tel: 06-6631-3611. Open every day: 17:00-23:00

From Tsuruhashi we head to Namba Station. We walk towards area that has many love hotels near exit 31 on the Osaka Metro Yotsubashi Line. Walch points out a restaurant that just happens to be located right between two of my favorite restaurants in Namba Tonsoku Kadoya and a very old izakaya called Notoya. If Tori Ichiban Honpo is as good as Walch says it is, then I won’t have to go very far to bar hop in this bustling area from now on.

“Many artists in Osaka are still lamenting the closure of the iconic Shinbun Onna Bar in Namba,” says Walch. It used to be the hangout and a major networking space of many independent local artists and musicians. One of the former customers is 74 year old Toshikazu Fujimoto, an art lover and patron, who is trying to fill the gap with his restaurant Tori Ichiban Honpo in Namba. Because it is quite spacious, it is also a good choice when it comes to gatherings and parties like bōnenkai (end of year) or shinnenkai (new year). Fujimoto-san always has time for a chat and the food is fresh and delicious. My personal favorite is the chicken nanban, fried chicken with tartar sauce.”

Fujimoto presents us with highball cocktails he made using top-shelf whiskey. They pack a punch, unlike the watered-down versions you get at most chain restaurants. Fujimoto explains that Tori Ichiban specializes in serving chicken like a yakiniku (Korean barbecue) restaurant. Customers can cook the meat themselves on the grill, but more often than not, Fujimoto will sit down at their table and personally cook the meat, using years of expertise to bring out the full flavor of the chicken.

Fujimoto says that his restaurant specializes in jidori chicken, a hybrid breed that is raised free-range on farms. They are fed only natural grains and are not given any animal by-products, hormones, or steroids. Jidori, which has been called the “Kobe Beef of chicken” is said to be so fresh that it is sometimes served raw, like sashimi. Fujimoto insist we try the grilled yakimoriawase set that contains 8 different parts of the chicken. It costs ¥3,150 and serves 4 people (a half set for two is ¥1,850). He said he orders an exquisite breed of jidori chicken from Tokushima in Nagasaki. Fujimoto carefully prepares our food and the result is wonderful, especially when dipped in the delicious selection tare sauces offered.

A visit to Tori Ichiban Honpo shows that there’s more to Japanese chicken than old favorites such as karaage and yakitori.

Theater Seven シアターセブン and Yodogawa River 淀川 (Juso)

Address: 1 Chome-7-27 Jusohonmachi, Yodogawa Ward, Osaka, 532-0024. Tel:06-4862-7733. Website.

“Although the underbelly in Osaka’s North has always been a bit underrated and had quite a bad reputation, it offers stunning views of Umeda’s skyline from the riverbanks of the Yodogawa. The river and its bridges also provide shelter and a safe haven for many homeless people. The movie “Yodogawa Asylum (淀川アジール)” (produced by Miro Daikokudo and directed by Yukio Tanaka) pays homage to the river and its inhabitants and is highly recommended. Juso is also the home of Theater Seven, one of Osaka’s very few independent movie theaters. In 2013, when my documentary KAN (KAN – 寺山修司を愛した男) had a one-week run at Theater Seven, Mikami Kan and I were staying at one of Juso’s cheapest business hotels. Every morning we would head out and meet for a coffee on the banks of Yodogawa river, admiring the view and having deep conversations.”

Roger Walch imdb page here

Roger Walch on Vimeo here